Silvio Monfardini, MD

Lodovico Balducci, MD

In part 1 of this two-part review, we looked at early pioneers in the field of medical oncology in Europe, as well as the development of international cooperative trials and the formation of European oncology societies (see related articles below). In part 2, we explore how the field of medical oncology evolved in individual European countries and pay homage to some of the many innovators who pursued this worthy goal, sometimes at the risk of criticism from their colleagues.

As we stated in part 1 of this history, our goal with this review of the pivotal years of oncology in Europe is to acknowledge the tremendous contributions of the early leaders in the field and to help young investigators learn from the past to better cope with the inevitable challenges of today and tomorrow. We begin here with some of the key pioneers in the development of medical oncology in Europe, grouped according to their home countries.

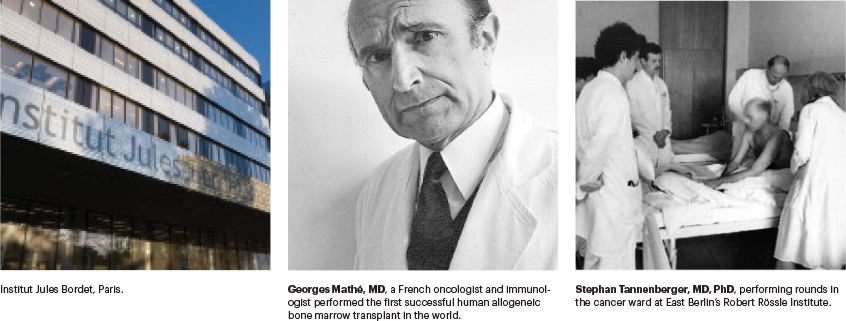

Belgium

In 1953, an independent medical service was created with the goal of establishing a comprehensive cancer center within the Institut Jules Bordet in Brussels, which was initiated by the Belgian medical oncology pioneer Henry Tagnon, MD. That first step paved the way for establishing the specialty of medical oncology throughout the continent of Europe.

In 1936, Dr. Tagnon had obtained his medical degree from the Université Libre de Bruxelles. After 4 years of training in internal medicine, he fled the Nazi invasion of his country and immigrated to the United States, where he continued his medical training, spending 6 years at Harvard Medical School in Boston, 7 years at Cornell University and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, and returning to Brussels in 1953.

In 1954, Yvon Kenis, MD, who would become the second President of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) in 1977, joined Dr. Tagnon as his first assistant in the newly created medical service at the Institut Jules Bordet. However, Dr. Kenis’ employment was met with derision by some members of the hospital staff, who predicted the impending shutdown of a service of cancer medicine they considered “superfluous.”

Eventually, Dr. Kenis left the Institut Jules Bordet to devote his time to the study of bioethics. In an address honoring Dr. Kenis’ work, Dr. Tagnon recounted the criticism against Dr. Kenis: “‘It is bad enough to sacrifice a man,’ meaning me, said they [referring to the critics], ‘but to draw in a young doctor, what madness!’” Dr. Tagnon went on to say: “We both ignored these encouraging words, because my American experience had taught me to disregard objections to a worthy project and Yvon because of his adventurous and optimistic turn of mind.”1

Dr. Tagnon published his first study on cytotoxic chemotherapy in 19542 and one on hormonal therapy for breast cancer in 1958.3 Over the next decade, Dr. Kenis produced a number of studies of systemic chemotherapies for cancer, including procarbazine for the treatment of -Hodgkin lymphoma.4

France

Born on July 9, 1922, in Sermages, France, Georges Mathé, MD, an oncologist and immunologist, is internationally recognized as a pioneer of medical oncology in Europe and of bone marrow transplantation. He was a founding member and first President of both the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) and the Society of Medical Oncology, now known as ESMO.

During World War II, while studying to become a doctor, Dr. Mathé participated in the French Resistance. Arrested by the Germans, Dr. Mathé was imprisoned in Poland and returned to Paris after the Russians liberated Poland. In the early 1950s, Dr. Mathé accepted an internship in immunology and oncology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and he later specialized in hematology while working with Jean Bernard, MD, Head of Hematology at Saint-Louis Hospital in Paris.

In 1958, a tragic accident catapulted Dr. Mathé to international renown, when six physicians in Yugoslavia were exposed to lethal amounts of radiation after a reactor malfunctioned. One physician died of the exposure, and one was relatively unaffected. Dr. Mathé brought the remaining four physicians back to Paris, where he infused them with donor leukocytes, which produced some degree of engraftment and saved their lives, making him the first physician to perform a human allogeneic bone marrow transplant.5

The importance of this experiment cannot be overstated. First, it suggested that peripheral leukocytes may be a source of pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells. Second, it suggested that a bone marrow transplant might be life-saving in conditions causing marrow failure. Third, the experiment provided examples of graft-vs-host disease. In later studies, it was discovered that this immune reaction was beneficial to the treatment of acute leukemia, allowing cures in some patients, a phenomenon conceptualized as “adoptive chemotherapy.” Based on this success, in 1963, Dr. Mathé and Maurice Schneider, MD, performed the first bone marrow transplant on a patient with leukemia.

After founding the Service of Hemato-oncology at the Institut Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, Dr. Mathé joined the Hôpital Paul-Brousse in 1961 as Head of the Hematology Service. Several years later, Dr. Mathé was instrumental in creating the Institute of Oncology and Immunogenetics, a cancer research center, including the French research unit INSERM (Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale) at Hôpital Paul-Brousse, where he led basic research for the next 29 years.

Dr. Mathé died on October 15, 2010, at the age of 88. During his long medical career, he played a major role in the development of new anticancer agents, including oxaliplatin and aclacinomycin, as well as new combinations of chemotherapy for various solid tumors. His accomplishments as a scientist, clinician, and teacher inspired a generation of other notable medical oncologists in France, including Jean-Louis Amiel, MD; Léon Schwartzenberg, MD; and Albert Cattan, MD, among others. Each one achieving an academic professorship in France and advancing medical oncology in Europe.

Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany)

In 1990, the Democratic Republic of Germany, also known as East Germany, was reunited with the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany). As a result, the initial history of the advent of medical oncology in Germany included the two separate countries. Here we detail the development of the specialty of medical oncology in both West and East Germany.

The term “medical oncology” was coined in the United States in the 1970s and imported to Europe, including East and West Germany. Prior to the 1970s, the practice of oncology was fragmented throughout Europe due to the inactivation of cancer institutions that existed prior to World War II. At the time, medical oncology was in the realm of hematologists, since most malignancies that were responsive to chemotherapy were blood cancers, and the fundamental differences between hematologic malignancies and solid tumors were not yet realized. Also, medical practice in Germany was so compartmentalized, it made the American model of interdisciplinary cancer care all but impossible to replicate. The combination of these two factors hindered the development of medical oncology in Germany.

Despite these difficulties, in the early 1960s, Carl Gottfried Schmidt,MD, widely considered the “Father of Medical Oncology” in Germany, was the first physician to recognize the need to treat cancer in a specialized cancer center and succeeded in establishing the first German Comprehensive Cancer Center on the campus of the University Clinic in Essen. There he established departments for medical oncology, radiotherapy, tumor cell biology, and molecular biology,6 eventually becoming Chair of the Division of Medical Oncology. In this role, Dr. Schmidt mentored the first generation of German medical oncologists, including Dieter Hossfeld, MD; Walter Gallmeier, MD; Ulrich Schäfer, MD; Siegfried Seeber, MD; Werner Böcker, MD; and Reinhard Osieka, MD.

These physicians went on to launch, in 1976, the Working Group for Internal Oncology of the German Cancer Society, which led to the creation of a clinical trial group under the direction of Hans-Joachim Schmoll, MD, and introduced Germany to multi-institutional cancer clinical trials.

Over the next several decades, Dr. Schmidt held several leadership positions, including President of the German Cancer Society from 1967 to 1978 and President of the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) from 1981 to 1984. He died in 2003 at the age of 81.

German Democratic Republic (East Germany)

Unlike the Federal Republic of Germany, in the German Democratic Republic the field of medical oncology originated at a cancer research institute, the Central Institute of Cancer Research, and not at a university. It was initiated by German oncologist and chemist Stephan Tanneberger, MD, PhD. While working at the renowned Robert Rössle Clinic in Berlin (the cancer center of the Academy of Sciences), Dr. Tanneberger gained experience in treating patients with cancer and spent time working in the lab, researching chemotherapy.

On the basis of his laboratory and clinical experience in the 1960s and 1970s, Dr. Tanneberger used chemosensitivity tests to individualize treatment for patients using only the drugs that appeared most effective—an approach to treatment that wasn’t studied and applied in the United States until a -decade later. He published a number of groundbreaking papers on his approach and brought the concept into the public arena.

When Hans Gummel, MD, a distinguished cancer surgeon and Director of the Robert Rössle Clinic, died suddenly in 1973, Dr. Tanneberger was named his successor, at the age of 38. To compensate for his lack of experience in heading an international institution, Dr. Tanneberger spent the next year visiting cancer centers around the world, including Roswell Park Memorial Hospital in Buffalo, New York, the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, the Institut Krebsforschung in Vienna, the All-Union Cancer Centre in Moscow, and the Imperial Cancer Research Fund in London.7

In 1978, while Director of the Robert Rössle Institute, Dr. Tanneberger joined the faculty at the UICC to teach courses in chemotherapy for a program chaired by Silvio Monfardini, MD, in Bombay (now Mumbai), India. The experience sparked an enduring interest to help patients with cancer in the developing world.Dr. Tanneberger died in 2018 at the age of 83.

The Netherlands

Herbert Michael (Bob) Pinedo, MD, PhD, is credited with creating the first Division of Medical Oncology in the Netherlands—and one of the first in Europe—at the Utrecht University Hospital in 1972. As Head of the Internal Medicine Clinic at the hospital, Dr. Pinedo noticed there was a one-sided surgical approach to treating cancer in the Netherlands and decided to study other treatment options. He founded an oncology working group, underwent training, and spent 2 years as a visiting scientist at the Laboratory of Clinical Pharmacology headed by Bruce A. Chabner, MD, at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in Bethesda, Maryland. There he studied the pharmacology of methotrexate in mice.

In 1979, following his work at the NCI, Dr. Pinedo returned to the Netherlands and was appointed Professor of Medical Oncology and Director of the Department of Medical Oncology at the VU University Medical Center in Amsterdam. He also became head of the pharmacologic laboratory of the Dutch Cancer Institute. While teaching at the university, Dr. Pinedo made it his priority to teach students the philosophy of translational research and the importance of bridging the two worlds of scientists and clinicians.8

In addition to methotrexate, Dr. Pinedo’s research contributed to the discovery of several other anticancer drugs, including platinum-based chemotherapies for patients with testicular and ovarian cancers. In 1983, he set up the New Drug Development Office at the EORTC in Amsterdam, which coordinated studies of the EORTC Early Clinical Trials Group.

Dr. Pinedo served as President of ESMO from 1987 to 1989 and is founder of the ESMO fellowship program. He is currently a Visiting Professor at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Italy

Medical oncology in Italy was developed within cancer institutes and in community and university hospitals, inspired by the work of many prominent clinicians and researchers, including Silvio Garattini, MD, Director of the Mario Negri Institute for Pharmacological Research, and Gianni Bonadonna, MD, considered the “Father of Italian Oncology.”

Born in 1934, Dr. Bonadonna was educated in Milan and obtained his fellowship training at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. He returned to Italy and joined the Istituto Nazionale Tumori in Milan, known predominantly as a surgical institution. There Dr. Bonadonna introduced the practice of medical oncology, which was initially received by colleagues with both sarcasm and pessimism. He later became Director of the Division of Medical Oncology at the institution.

Dr. Bonadonna’s most formidable legacy is in his pioneering work in the area of combination chemotherapy. He drove the success of doxorubicin in Italy and initiated the first step toward a formal set of rules for new drug development in oncology. Doxorubicin had been developed by Federico Arcamone, MD, and tested by Aurelio di Marco, MD, at the Istituto Nazionale Tumori. The initial findings with the agent, indicating a broad spectrum of antitumor activity, as well as cardiac effects, were later confirmed in large studies by Dr. Monfardini in Italy in 1969, as well as by researchers in the United States.

The most important studies led by Dr. Bonadonna were in the treatment of breast cancer and Hodgkin lymphoma. In 1975, he presented the first report of a randomized controlled study on the efficacy of the combination regimen containing cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF), which showed a reduced recurrence rate and prolonged survival in women with operable breast cancer. CMF remained the standard of care for adjuvant treatment in breast cancer until 1980 and is still the preferred therapy of many clinicians. Dr. Bonadonna is also considered the father of the combination chemotherapy regimen ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine) for the management of Hodgkin lymphoma, which is still the gold standard treatment of the disease.

It is impossible to overstate the influence that Dr. Bonadonna had on the development of the field of medical oncology throughout Italy and the world. He was honored for his many achievements with numerous awards, including ASCO’s naming of the Gianni Bonadonna Breast Cancer Award, which recognizes an active clinical and/or translational researcher with a distinguished record of accomplishments in advancing the field of breast oncology who also has exceptional mentoring abilities.

After suffering a near-fatal stroke in 1995, Dr. Bonadonna founded the Michelangelo Foundation and wrote books about his own experience of illness, which revealed his spiritual reawakening. He died on September 7, 2015, at the age of 81.

Other Italian Notables

There are several other early pioneers in the field of Italian medical oncology we would like to acknowledge, including Gino Luporini, MD, who became Director of the first Medical Oncology Unit at an Italian community hospital, the San Carlo Borromeo Hospital in Milan. While there, Dr. Luporini and his colleagues, Franco Montinari, MD; Maurizia Clerici, MD; and Roberto Labianca, MD, introduced the concept of supportive and palliative care.

Other Italian cities, including Padua, Rome, and Naples, spawned notable contributors to the field of medical oncology. In 1966, in Rome, Aldo Barduagni, MD, headed the first Division of Medical Oncology at the Regina Elena Cancer Institute. His pupils included Federico Calabresi, MD; Massimo Lopez, MD; Edmondo Terzoli, MD; and Francesco Cognetti, MD.

Eight years later, in Naples, Angelo R. Bianco, MD, launched an oncology division within the Department of Medicine of the University of Naples Federico II Medical School after spending a number of years at the NCI, as a visiting scientist. His effort led to the institution of the first University Chair in Medical Oncology and contributed to the recognition of medical oncology as a medical specialty in Italy.

And, in 1975, in Padua, Mario V. Fiorentino, MD, organized a medical oncology service within the Division of Radiation Oncology at the Civil Hospital of Padua. His alumni included Giuseppe Cartei, MD; Vinicio Fosser, MD; Adriano Paccagnella, MD; and Vittorina Zagonel, MD; all of them became chiefs of medical oncology units in major hospitals.

Spain

By the end of the 1960s, there were several oncologists involved in developing medical oncology in Spain, although the field wouldn’t be officially recognized as a specialty in the country until 1981. At the Fundación Jiménez Díaz University Hospital in Madrid, Jesús de Vicente, MD, worked with Argentinian medical oncologist Hernán Cortés-Funes, MD, PhD, to establish a specialty in internal medicine and medical oncology in Spain.9

After his medical training in Madrid, Dr. Cortés-Funes participated in the Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program at the NCI. In 1978, he cofounded the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology with Dr. Vicente, who served as the society’s first President. Dr. Cortés-Funes served as President of ESMO from 1990 to 1991.

Other early Spanish pioneers include José Maria Montero, MD; Manuel Gonzáles Barón, MD; Ángel Durán Pérez Navarro, MD; and Salvador Juárez Alonso, MD. By the mid-1970s, medical oncology departments had been established in many regions of Spain. Of note was the contribution of Antonio Brugarolas, MD, who, after training at Roswell Park Memorial Hospital, returned to Spain in 1973 as Head of Medical Oncology at Asturias General Hospital in Oviedo. He played an important role in the recognition of the medical oncology specialty in Spain.

Switzerland

Some of the early influencers of medical oncology in Switzerland include Georg Martz, MD, who established a medical oncology unit at the University Hospital in Zurich in 1960; his assistant Kurt Brunner, MD; Pierre Alberto, MD, who, in 1988, played a key role in establishing the ESMO Examination for Medical Oncology; and Franco Cavalli, MD, FRCP, who was born in Locarno, a town in the Italian region of Switzerland, and served as Scientific Director of the Oncology Institute of Southern Switzerland in Bellinzona until 2017.

Dr. Brunner did his training at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and Roswell Park Memorial Hospital, where he gained experience in how to design and conduct prospective randomized cancer clinical trials under the tutelage of David Karnofsky, MD; Joseph Burchenal, MD; and James Holland, MD. In 1965, he published a seminal paper on new cytotoxic agents. He later became Head of the Division of Medical Oncology at the University Hospital of Bern.

Dr. Brunner was an early advocate of the importance of developing a national cooperative group for clinical research on new cancer treatments, and he pleaded with the Swiss parliament to authorize the launch of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK). Under his direction, SAKK conducted numerous clinical trials, including a pivotal study showing the benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy for non–small cell lung cancer.10

Further Achievements of Early Swiss Oncologists

For many years, Dr. Alberto was Professor of Medical Oncology at the University Hospital of Geneva, where he pioneered multiple aspects of modern, integrated cancer care. A strong advocate of multicenter clinical trials, he was elected President of SAKK in 1975.

Dr. Alberto was among the first to recognize the importance of communicating with patients about their cancer and understanding the challenges that their diagnosis and treatment brought to their everyday lives. He also introduced the use of specialist cancer nurses into his practice and provided a model for training nurses in oncology care.

After finishing medical school in 1968, Dr. Cavalli spent the next 2½ years studying psychiatry and then trained in internal medicine, before switching to oncology. In a 2013 interview with The ASCO Post, Dr. Cavalli explained his decision: “By the time I started internal medicine, I was disappointed in psychiatry,” he said. “During this period, I met a fascinating professor named Kurt Brunner, MD, who influenced my decision to switch careers. He said that my combined interests in human behavior and science made oncology a perfect fit. He was right.”11

Dr. Cavalli specializes in the treatment of lymphomas and was the founder of the International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma, the leading international forum for basic and clinical research in lymphomas, which is now held every 2 years in Lugano, Switzerland. He was also the founding Editor and Editor-in-Chief of the Annals of Oncology, Europe’s premier medical oncology journal. Dr. Cavalli has been a leading voice in spreading the practice of medical oncology in developing countries, especially in Central America.

United Kingdom

In correspondence with Dr. Monfardini for this article, John F. Smyth, MD, Assistant Principal and Emeritus Professor of Medical Oncology at the University of Edinburgh and ESMO Past-President, described the development of medical oncology in the United Kingdom: “In the UK, [medical oncology as a specialty] started in the 1960s at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London. Gordon Hamilton Fairley, MD, was a consultant clinical hematologist, but he had a special interest in Hodgkin disease and acute myeloid leukemia and was the first physician to be allocated beds [in the hospital] exclusively for malignant diseases. He named his department Medical Oncology,” Dr. Smyth recounted.

“In 1970, London University gave him a Chair, and he was the first Professor of Medical Oncology in the United Kingdom. The development of the specialty was fostered by two philanthropic organizations: the Cancer Research Campaign (CRC) and the Imperial Cancer Research Fund (ICRF), which funded professorships and training opportunities. The leaders of the National Health Service were not convinced that management of cancer should be considered a funding priority. In 1973, Derek Crowther, FRCP, FRCR, became the second Professor of Medical Oncology [in the UK], at the Christie Hospital in Manchester. After working with Gordon, he obtained the Chair of Medical Oncology at the Christie, funded by the CRC in 1974,” Dr. Smyth said.

Dr. Smyth continued: “In 1976, Michael Whitehouse, MD, also of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, was appointed to another CRC Chair in Southampton. These three units were originally focused on the treatment of lymphoma, which led to some controversy with British hematologists. When they started treating solid tumors, conflicts developed with radiation oncologists.”

A Lasting Legacy

Sadly, Dr. Fairley was killed by an IRA terrorist bomb while walking his dog in London on October, 23, 1975. He was just 45 when he died, but he left a lasting legacy on the development of medical oncology as a medical specialty in the United Kingdom. In recognition of his contributions to the field of medical oncology and to honor his memory, ESMO has named an award after him—the Hamilton Fairley Award, which is presented to candidates who are internationally recognized for lifetime achievements in science and clinical/laboratory research.

In 1978, Dr. Smyth was appointed the first Chair of Medical Oncology in Scotland, funded by the ICRF at the University of Edinburgh. Prior to that appointment, Dr. Smyth led a lung cancer unit at The Royal Marsden Hospital in London and was determined to treat solid tumors, especially lung, breast, and ovarian. In Scotland, Dr. Smyth was welcomed by both surgical and radiation oncologists.

In his Presidential Address at the Association of Cancer Physicians, in 2007, Dr. Crowther recalled that “the development of medical oncology … had its roots in academia with clinical research and teaching within a university and hospital environment. Medical oncology became a recognized medical subspecialty in the United Kingdom under the auspices of the Royal College of Physicians, and academic departments of medical oncology were developed outside London in England and Scotland during the 1970s.”12

We would be remiss if we didn’t mention the enormous contributions of Kenneth Bagshawe, CBE, FRCP, FRCOG, FRCR, to the field of medical oncology. He is best known for his pioneering research in choriocarcinoma in the 1950s and 1960s and his subsequent development of the methotrexate/mercaptopurine combination regimen to treat the disease. Dr. Bagshawe provided medical care for patients with cancer before medical oncology was defined as a specialty.

After working at St. Mary’s Hospital Medical School from 1946 to 1952, Dr. Bagshawe became a research fellow at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore and later served as Professor of Medical Oncology at Charing Cross Hospital Medical School in London, and Chair of the Cancer Research Campaign’s Scientific committee.

As mentioned in part 1 of this feature, we have attempted to name many of the pioneers who facilitated the development of medical oncology in Europe, but we realize there are individuals absent in this discussion whocontributed significantly and to whom we owe great debt and also extend our gratitude. We have endeavored to outline the recent history of medical oncology in Europe, concentrating on progress made beginning in 1985. Our goal in chronicling this history is to encourage young investigators to learn from the past, to better cope with the challenges they may face today and in the future, and to bring the same level of optimism and determination to their work that these European pioneers in medical oncology brought to theirs. We are optimistic about future advances in medical oncology worldwide, and we hope you have enjoyed this historical perspective.

DISCLOSURE: Drs. Monfardini and Balducci reported no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Tagnon H: Address in honor of Dr. Yvon Kenis on the occasion of his retirement from the Service of Medicine at Institut Jules Bordet, 29 June 1987. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 24:507-508, 1988.

2. Tagnon H: Chemotherapy of cancer: Current research and hopes. Ann Soc R Sci Med Nat Brux 7:139-151, 1954.

3. Van Rymenant M, Tagnon H: Role of hormones as modifyingagents of the hormonal status in cancer: Hormone therapy of generalized breast cancer. Acta Chir Belg 57(suppl 1):79-129, 1958.

4. Kenis Y: On the treatment of generalized Hodgkin’s disease with procarbazine (Natulan). Brux Med 48:447-456, 1968.

5. Martin D: Dr. Georges Mathé, transplant pioneer, dies at 88. The New York Times, October 20, 2010. Available at www.nytimes.com/2010/10/21/health/research/21mathe.html. Accessed October 11, 2021.

6. Hossfeld DK: Obituary: Professor Carl Gottfried Schmidt. Eur J Cancer 40:921, 2004.

7. Fricker J: A reverence for life in turbulent times. Cancer World, November/December 2008, pp 26-32. Available at https://archive.cancerworld.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/2457_pagina_26-32_masterpiece.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2021.

8. Wagstaff A: Bob Pinedo: Bringing two worlds together. Cancer World, September-October 2004, pp 28-33. Available at https://archive.cancerworld.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Masterpiece-1.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2021.

9. González Barón M: [Notes on the beginnings of medical oncology in Madrid], in [History of Medical Oncology in Spain]. Madrid, Spanish Society of Medical Oncology, 2009.

10. Brunner KW, Marthaler T, Müller W: Effects of long-term adjuvant chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide (NSC-26271) for radically resected bronchogenic carcinoma. Cancer Chemother Rep 4:125-132, 1973.

12. Crowther D: A brief history of medical oncology: A personal perspective. The presidential address at the 2007 meeting of the Association of Cancer Physicians.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the following colleagues who contributed many hours of their time in the reconstruction of the history of the establishment of medical oncology in Europe, which was often provided in the absence of published material.

Silvio Garattini, MD, Former Director of the Mario Negri Institute for Pharmacological Research (1961–2018); research scientist, physician, and professor in chemotherapy and pharmacology

Maurice Schneider, MD, of the University of Nice Sophia Antipolis, Nice, Provence-Alpes-Cote d’Azur, France

John Smyth, MD, Assistant Principal at the University of Edinburgh; Emeritus Professor of Medical Oncology, University of Edinburgh

Peter Voswinkel, Medical Historian, German Society of Haematology and Oncology, Berlin

Dieter Hossfeld, MD, of the Medizinische Klinik, Universitätsklinikum Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany

Hans-Joachim Schmoll, MD, Professor of Medicine Klinik Innere Medizin IV-Hämatologie-Onkologie, Martin Luther University in Halle-Wittenberg, Germany

Franco Cavalli, MD, Professor of Medical Oncology at the Medical Facility in Bern, Switzerland; Scientific Director, Oncology Institute of Southern Switzerland, Bellinzona, Switzerland

Matti S. Aapro, MD, President, European Cancer Organisation (2020–2021); Dean, Multidisciplinary Oncology Institute in Genolier, Switzerland

Alberto Costa, MD, PhD, Chief Executive Officer of the European School of Oncology

Dr. Monfardini is Chair of the European School of Oncology program on history of European Oncology, in Milan, Italy. Dr. Balducci is Professor of Oncology and Medicine at the University of South Florida College of Medicine and Chief of the Division of Geriatric Oncology, Senior Adult Oncology Program at H. Lee Moffit Cancer Center & Research Institute, Tampa, Florida.