Periodic drug shortages are an unavoidable reality in our complicated pharmaceutical supply chain; however, over the past several years, drug shortages have expanded to crisis levels, putting vulnerable patients at risk. In 2010, there were 178 drug shortages reported to the FDA, 132 of which were sterile injectable products. Since most chemotherapy is delivered by injection, the shortages have hit the oncology community especially hard.

Despite the inevitable finger-pointing, this is a complex issue with no single cause and no clear end in sight, puzzling the regulators and legislators looking for solutions. The ASCO Post recently spoke with several leading health-care experts to gain insight into the drug shortage problem.

FDA: Faster Communication Needed

Capt. Valerie Jensen, RPh, Associate Director

of FDA’s Drug Shortage Program, told The ASCO Post that drug manufacturers are not required by law to report information about shortages. “We usually find out about shortages through interactions with health-care professionals or associations. Our primary role is to contact manufacturers that are having problems and offer assistance to ramp up production by, for instance, helping them find additional manufacturing sites or new suppliers,” said Capt. Jensen.

Capt. Valerie Jensen, RPh, Associate Director

of FDA’s Drug Shortage Program, told The ASCO Post that drug manufacturers are not required by law to report information about shortages. “We usually find out about shortages through interactions with health-care professionals or associations. Our primary role is to contact manufacturers that are having problems and offer assistance to ramp up production by, for instance, helping them find additional manufacturing sites or new suppliers,” said Capt. Jensen.

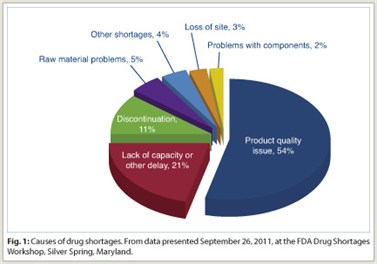

Capt. Jenson explained that most of the injectable shortages that affect oncologic agents stemmed from product quality-assurance issues and manufacturing delays (Fig. 1). “We’ve seen an upswing in particulate  contamination occurring in injectable product vials. There’s also been an increase in sterility-issue production delays,” commented Capt. Jensen.

contamination occurring in injectable product vials. There’s also been an increase in sterility-issue production delays,” commented Capt. Jensen.

Moreover, during the past few decades, the pharmaceutical manufacturing industry has consolidated. Consequently, most sterile injectables have only one manufacturer that produces at least 90% of a particular drug. “Getting a product line up and running is an involved, time-consuming process. With fewer manufacturers, the market has less capacity to produce sterile injectable drugs if a production problem occurs at one site. To that end, we are encouraging companies to report problems early and to have backup plans, such as alternative production sites,” said Capt. Jensen.

Legislative Proposals

Joseph M. Hill, MA, Director of Federal Legislative Affairs for the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) echoed FDA’s assertion that manufacturing issues are the biggest cause of shortages. “The shortage problem is multifactorial, but what we are hearing about most are production line issues, such as line contaminations that force shutdowns.”

Joseph M. Hill, MA, Director of Federal Legislative Affairs for the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) echoed FDA’s assertion that manufacturing issues are the biggest cause of shortages. “The shortage problem is multifactorial, but what we are hearing about most are production line issues, such as line contaminations that force shutdowns.”

Mr. Hill, who has done considerable work on Capitol Hill, commented that the President’s recent Executive Order 13588 (Reducing Prescription Drug Shortages) has helped call attention to the seriousness of the problem. “The Order gives no new authority, but it signals that no one can hide from the problem, because it’s reached the White House,” said Mr. Hill.

Asked about legislative solutions, Mr. Hill noted that there are two bills—one in the House, one in the Senate—that establish early warning systems that would mandate manufacturers to notify the FDA as soon as a problem occurs, or within 6 months in the case of impending discontinuation of a drug. The Preserving Access to Life Saving Medications Act (S. 296 and H.R. 2245) was introduced by Sens. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and Robert Casey (D-PA) in the Senate and by Reps. Diane DeGette (D-CO) and Thomas Rooney (R-FL) in the House of Representatives.

Asked about legislative solutions, Mr. Hill noted that there are two bills—one in the House, one in the Senate—that establish early warning systems that would mandate manufacturers to notify the FDA as soon as a problem occurs, or within 6 months in the case of impending discontinuation of a drug. The Preserving Access to Life Saving Medications Act (S. 296 and H.R. 2245) was introduced by Sens. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and Robert Casey (D-PA) in the Senate and by Reps. Diane DeGette (D-CO) and Thomas Rooney (R-FL) in the House of Representatives.

“This legislation would simply subject companies to civil monetary penalties for failure to report problems that might cause shortages or delays in production,” said Mr. Hill.

ASHP is supportive of both bills, Mr. Hill explained, because the FDA has cited that the agency has been able to avoid 195 shortages this year alone, when they had early warning information available. “Both bills require manufacturers to work with the FDA on contingency plans for the production of injectable drugs. For instance, if the issue were related to raw materials, companies would need a backup source. Or manufacturing redundancies could be created with additional inventory,” said Mr. Hill.

Although the details of the contingency plans are not spelled out, ASHP felt it was a way to get the ball rolling. “We really need to think about having sustainable and robust backup plans in place, especially in the case of lifesaving medications,” concluded Mr. Hill.

Is the Physician Payment Model to Blame?

In a recent New England Journal of Medicine editorial that garnered much attention in the lay press,1 the authors wrote that two economic incentives are the culprits for the shortage crisis: Manufacturers have slowed production of generic drugs due to lowering profits, and oncologists have more financial incentive to administer brand-name drugs than injectable generics.

Responding to the latter supposition, Derek Raghavan, MD, PhD, President, Levine Cancer Institute, commented, “I appreciate the authors’ attempt to address the complex and vexing problem of drug shortages, in which the end result is suboptimal care for our patients. For instance, several drugs on the shortage list are used in acute leukemia, which is an example of a disease where the gains have been hard fought and hard won. For a doctor to have to deviate from the best management strategy for his or her patient because of a drug shortage is nothing short of a national disgrace,” he noted.

Responding to the latter supposition, Derek Raghavan, MD, PhD, President, Levine Cancer Institute, commented, “I appreciate the authors’ attempt to address the complex and vexing problem of drug shortages, in which the end result is suboptimal care for our patients. For instance, several drugs on the shortage list are used in acute leukemia, which is an example of a disease where the gains have been hard fought and hard won. For a doctor to have to deviate from the best management strategy for his or her patient because of a drug shortage is nothing short of a national disgrace,” he noted.

“That said,” Dr. Raghavan continued, “the editorial attributed part of the shortage problem to private practice community oncologists who are supposedly purchasing and hoarding more expensive brand-name agents. As an academic physician, I’ll defend my colleagues in the community setting by stating that I am unaware of any reliable data to support this proposition, and I actually think it is illogical—many of the current shortages relate to nononcological agents and pain medications, and have nothing to do with patterns of oncology practice.”

Dr. Raghavan stressed that, absent hard data, the most likely explanation for the problem is actually a growing number of generic drugs that do not have a sustainable level of profitability for the manufacturer. “It has nothing to do with purported practice patterns in which physicians opt to use higher-priced drugs to increase their margins. In fact, with respect to patient costs, many oncologists choose the least costly alternative. To assert that private practice oncologists are making treatment decisions based only on profitability of one drug over another, leading to drug shortages, is an offensive and unfounded theory,” concluded Dr. Raghavan.

Take Medicare Out of Pricing

Asked to weigh in on the shortage issue, internationally regarded policy expert Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, Diane v.S. Levy and Robert M. Levy University Professor and Vice Provost for Global Initiatives at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, said, “At this juncture, it’s important to note that we are not exactly sure what’s driving the shortages.”

Asked to weigh in on the shortage issue, internationally regarded policy expert Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, Diane v.S. Levy and Robert M. Levy University Professor and Vice Provost for Global Initiatives at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, said, “At this juncture, it’s important to note that we are not exactly sure what’s driving the shortages.”

Dr. Emanuel explained that because of a lack of resources, the FDA’s ability to help manufacturers that are experiencing production issues get back on line has been hampered, which contributes somewhat to the problem.

“However, the payment system, particularly the advent of the Medicare Modernization Act (MMA), which substantially lowered drug reimbursement rates, is a larger part of the problem. If manufacturers were making larger per-dose profits on generic drugs, they wouldn’t allow their production lines to go down.”

Dr. Emanuel conceded that there is no “magic bullet” cure for the shortages. Although he does not advocate returning to the pre-MMA reimbursement model that created perverse incentives, he offered that taking Medicare out of the pricing system would help stabilize the market. “When these injectable drugs come off patent, put them on Part B. After about 18 to 24 months, the prices would drop by about 90%. Let pharmacy benefit managers handle them and you’ll see market-driven fluctuations,” said Dr. Emanuel, adding that if the law of supply and demand is allowed to work, drug shortages will cause the prices to rise, giving manufacturers incentives to fill the need.

From ASCO

ASCO President Michael Link, MD, commented, “Everyone agrees that the drug shortage crisis is a multifactorial problem. Production issues in the supply chain are definitely part of the problem that needs to be addressed. However, many of us believe that the underpinning issue is an economic factor. The reality is that many of these generic drugs are priced so low that there’s no incentive for manufacturers to produce them or invest in the necessary infrastructure to prevent or fix a production problem.”

ASCO President Michael Link, MD, commented, “Everyone agrees that the drug shortage crisis is a multifactorial problem. Production issues in the supply chain are definitely part of the problem that needs to be addressed. However, many of us believe that the underpinning issue is an economic factor. The reality is that many of these generic drugs are priced so low that there’s no incentive for manufacturers to produce them or invest in the necessary infrastructure to prevent or fix a production problem.”

“For our part,” he continued, “the Society has been at the forefront of this issue, getting the message out so that it gains the national attention it deserves. This is not just a cancer problem; it is a widespread issue affecting many generic drugs that patients across the country depend on. From our perspective, although multiple issues come into play, the most straightforward way, although admittedly difficult in today’s economic environment, would be to find creative ways to increase the market price of generics—as in Europe, where the shortages are less of a problem—so that companies have enough profit margin to make production, safety, and distribution viable.”

Conclusions

As Dr. Emanuel noted, there is no magic bullet that can prevent all drug shortages. The complexity of manufacturing processes, the requirement for safe and high-quality products, and consolidation and globalization of the pharmaceutical supply chain all contribute to fluctuating product supplies. Moreover, various economic factors driven by Medicare reimbursement policy and the stressors of free-market supply and demand cycles influence profitability incentives for drug manufacturers.

With all these factors in mind, there are fundamental measures that Congress, FDA, and other stakeholders can apply to ensure that the U.S. health-care system does not again experience the crisis-level shortages that doctors and their patients are currently struggling with (see sidebar on “Policy Recommendations”). ■

Disclosure: Dr. Link has received research support from Seattle Genetics. Capt. Jensen, Mr. Hill, and Drs. Emanuel and Raghavan reported no potential conflicts of interest.

Reference

1. Gatesman ML, Smith TJ: The shortage of essential chemotherapy drugs in the United States. N Engl J Med 365:1653-1655, 2011.