In this installment of The ASCO Post’s Global Oncology series, guest editor Chandrakanth Are, MBBS, MBA, FRCS, FACS, spoke with Isabel T. Rubio, MD, PhD, Head of Breast Surgical Oncology at Clinica Universidad de Navarra, Madrid. Dr. Rubio is active in many societies and is a founding member and past President of the Spanish Association of Breast Surgeons (AECIMA), European Society of Breast Cancer Specialists (EUSOMA) President (2020–2023), European Society of Surgical Oncology (ESSO) President (2022–2024), member of the Exceutive Committee of the European Cancer Organization (ECO), member of the Board of the Breast Surgical Division of the European Union of Medical Specialist (UEMS), a member of the American Society of Breast Surgeons, and a member of the Outreach Committee of the Society of Surgical Oncology (SSO).

Isabel T. Rubio, MD, PhD

An Early Introduction to Medicine

Please tell us a bit about where you were born and why you chose a career in medicine.

I was born in Salamanca, a city in northwestern Spain. It is home to the University of Salamanca, which was founded in 1218 by King Alfonso IX, one of the oldest universities in Europe. My father was a head and neck surgeon, and my mother was a pediatrician, so I was living in an environment of medicine as far as I can remember. I think largely because of that early introduction to medicine, my own path was sort of destined. When I was obtaining my medical degree at the Faculty of Medicine in Salamanca, I had the opportunity to join my father in the operating room, and I soon realized I would like to be a surgeon. I didn’t have any specialty in mind, so I just did a general surgery residency. And while doing that, I usually spent my summers in the Cottage Hospital in Santa Barbara, where I observed another way of doing medicine and surgery.

What incited your interest in breast cancer?

When I was doing my residency, women with breast cancer were generally treated by mastectomy alone, as there were very few options. I thought it was not fair, because there were patient preferences or discussions. So, I realized this was a clinical area that desperately needed to improve; plus, it was very challenging and had an exciting future that I wanted to be part of. It was that simple.

GUEST EDITOR

Chandrakanth Are, MBBS, MBA, FRCS, FACS

Professional Path

Please tell us about your career path to your current position.

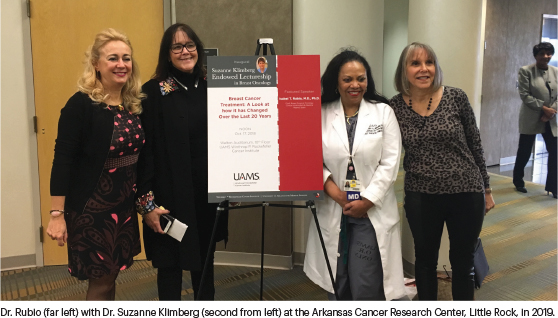

During my residency, and still to this day in Spain, there is no postgraduate training in breast surgical oncology. So, I looked for a breast surgical fellowship opportunity in the States. I found two potential positions—one at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and another at the University of Arkansas for Medical Science. However, I’d have to wait a year for the UCLA fellowship, so I interviewed with V. Suzanne Klimberg, MD, and got that fellowship. I spent 2 years in Little Rock doing a breast surgical oncology fellowship, which was very good training. It opened my eyes to different ways of doing medicine and a challenging world of cancer surgery that was unlike anything during my general surgery residency. It was a very fruitful time there, and in that period, Suzanne Klimberg became my mentor. I learned what a mentor meant and how important it is to develop your professional and personal career.

Then I went to MD Anderson Cancer Center for 7 months, because at that time, they were planning to open an MD Anderson branch in Madrid. My experience working in the multidisciplinary cancer care approach was extremely valuable, as was the whole experience in the United States.

After that, I returned to Spain and moved to Barcelona to the Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, where the Chief of Medical Oncology was Jose Baselga. He was looking for breast cancer surgeons, and I spent 15 years there as Head of the Breast Surgical Unit, working very closely with Dr. Baselga. He had a great vision of how to develop translational research, so it was also an important period of career development.

European Cancer Landscape

Can you tell us about the cancer landscape in Europe, from your perspective as President of EUSOMA and Head of Public Affairs at ESSO?

In Europe, cancer is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity, and it also is a major economic burden. The number of people diagnosed with cancer in Europe has been rising about 50% in the past 20 years. Europe also has an aging population, which adds to the cancer burden. There are differences in survival rates depending on the cancers and the demographics across the diverse European continent.

It’s something that we are really working on. There has been a Europe Beating Cancer Plan, which has been promoted and designed by the European Commission. The aim is to tackle all the cancer pathways; to that end, they have focused on four key action points: prevention, diagnosis and treatment, early detection, and quality-of-life issues. This is a huge program, where they’ve invested millions of euros, with the goal of reducing cancer care inequities in Europe.

Can you offer a view of the outcomes landscape across the 28 countries of Europe?

Probably the main differences in approach and outcomes are between the Western European countries and the Eastern European countries. For example, we established breast cancer screening programs in the late 1980s in Spain and in other Western European countries. The screening compliance rate in Sweden is about 95%; however, in Romania, it’s only 9%. So, that represents a huge disparity between a Western and Eastern European country. And we see a similar trend in colorectal and cervical cancers. Cancers are detected at a later stage, and survival is decreased. Naturally, it’s a huge public health problem.

We also see more access-to-care barriers in the Eastern part of Europe plus a lack of innovative medical technologies, access to drugs, to cancer centers, to support groups, among other things. It will take a huge effort to close the gap between West and East in Europe, but we’re working on it, it will be a great effort to try to implement all the EU recommendations into the Member States.

From the day you started your career, how has cancer care changed in Europe?

Over the past 20 years, the changes have been so great. I think first and foremost has been the widespread acceptance and use of cancer prevention screening programs. And the public awareness about lifestyle-related cancers has also been a tremendous advance. Along with that, we’ve seen the birth of personalized cancer care and the growing use of less invasive (surgical de-escalation treatments) and less toxic treatments. Quality-of-life measures and palliative care have also emerged and become part of mainstream oncology practice, adding better outcomes for survivors. And now, targeted therapy is here to stay, and new immunotherapies have increased survival rates in patients who were running out of options in systemic treatment.

The progress we’ve seen will build momentum, and over the next 10 years, I’m confident we will solve many of the challenges that 20 years ago we never dreamed were possible. It’s a very exciting time in oncology.

Goals of the European Society of Breast Cancer Specialists

How are you addressing those disparities in your leadership role as President of EUSOMA?

For one, we are doing a lot of advocacy to get more patients into cancer centers, as it is one way to ensure high-quality cancer care for all our patients with cancer. But Europe is kind of a difficult continent; despite all our data-driven recommendations, every country has its own pricing and reimbursement guidelines that drive its decisions. So, reaching consensus is very difficult. Moreover, oncology at large in Europe has a very productive working relationship, but each separate state and nation has its own system, which doesn’t always agree with our recommendations. And, as you know, even in a wealthy country like the United States, there are lively debates and disagreements over how best to allocate cancer care resources.

EUSOMA has developed a set of benchmark quality indicators that could be adopted by breast centers to allow standardized auditing and quality assurance and to establish an agreed minimum standard of care. If you don’t measure how you manage patients with cancer, you will not be able to improve anything. The EUSOMA breast cancer database is probably one of the largest in Europe.

Role of Breast Cancer Surgeons

There’s an ongoing debate about general surgeons performing cancer surgery. What’s your opinion on this issue?

The truth is that when you’re trained as a general surgeon, you think you can do cancer surgery also. I appreciate that level of confidence, but cancer surgery requires a deep knowledge of cancer biology that many general surgeons simply don’t have. And then the science behind cancer treatments, diagnosis, and prevention is moving so fast that even I have trouble keeping up with all the publications.

I am a breast cancer specialist. I cannot imagine a surgeon operating on a hernia in the morning and doing breast cancer surgery in the afternoon. How could you keep up with the evolving new techniques in multidisciplinary cancer care, attend meetings, and tumor boards? Therefore, I think we need to convince governments and every member state that patients with cancer deserve to have surgery from cancer surgeon specialists, because otherwise they are not going to receive high-quality cancer care.

That said, given that about 80% of our patients with cancer will need surgery, ESSO plans to standardize surgical oncology interventions by creating a core curriculum that can be applied across the continent. Taking challenges that affect all our patients and standardizing the management approach is one way to create better outcomes across the board. In other words, we need to be specific about identifying a need and developing a remedy. Otherwise, we can lose focus by seeing things too broadly.

Research Interests

Can you briefly describe the research you’re involved in?

We’re researching the de-escalation of surgical treatments, because we have realized that sometimes bigger surgery doesn’t always confer the best outcomes. We just need to perfect the process of matching patients with the best type of surgery. The use of genomic platforms, not only for prognosis and predictive treatments in cancer but also for prevention, along with liquid biopsy methods to detect high-risk patients will be exciting research over the next 5 years. Another area of improvement is in communication to patients with cancer and how to improve the shared decision-making. Cancer surgeons need to be trained in communication as well.

As a community, I think it’s important to acknowledge the role of big data in the evolution of oncology. We see patients, operate on patients, do research, but sometimes we lack evidence-based data of the clinical results of our efforts to share with other cancer centers. For example, in Europe, research has shown there are poor-quality data capturing real-world studies. We need to make a collaborative effort to gather all the data in databases, so we can share and compare the clinical information among cancer centers, which will help us understand more about outcomes in the real-world setting.

Inside the European Society of Surgical Oncology

I know you are halfway through your presidency with the European Society of Surgical Oncology. Can you tell us about your organization?

The European Society of Surgical Oncology was established in 1981, and it has national affiliated societies from the 21 member states in Europe. In addition, we also have many partnerships with other international societies, and one of our missions is to advance the practice of cancer surgery through training and education. There is a whole portfolio of webinars, hands-on courses, and fellowships in all organ-based cancers.

We also are involved in trying to reduce the disparities in cancer surgery quality between the countries. I am the first female president and am honored that we have included an inclusion and equity committee in the society, because we need to support and promote women in the field of surgical oncology. If we look at medical schools and general surgery residencies, the number of female surgeons is increasing. Yet we don’t see that increase as much into leadership positions, and I think it’s something we need to focus on. We have already studied the gaps; we know where the problem is, now we need to find the solution.

Words of Wisdom for Junior Faculty

Let’s say I have a junior faculty member who wants to become you. What would your advice be?

Over the past decade or so, the world has realized there needs to be a change in the way women in the medical workforce are viewed. And by that I’m not saying we need to give women benefits that we don’t give to others, but we need to realize that women bear children and are primary caregivers. In the past, we had to choose between having children or a career. Our unconscious attitudes, which have arisen from preformed associations, can affect what we say and do without our knowledge, and they may even contradict our conscious beliefs, which can affect how women progress in surgery.

And without enough women at the top, where are the role models for future female surgeons? How will the gender gap in cancer surgery ever be closed? There are too few female mentors in surgery, and the lack of female role models in surgical leadership contributes to the perpetuation of male stereotypes.

We need men to work all this out too and to understand there is a problem with gender bias. To solve it, there’s a need for everyone to realize some things need to change. And I think that sometimes, women don’t ask enough or demand enough. So, my advice to women in oncology who want to move up the career ladder into leadership positions is to be assertive and confident. Fortunately, many of the leading oncology societies are making efforts to support women’s career efforts.

The Impact of COVID-19 on Cancer in Europe

Can you briefly tell us about the effect of COVID-19 in the European cancer population?

COVID-19 has left behind a horrible effect on the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer and in cancer in general. I think over the next couple of years, we will see the multiple ways the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted cancer. Given how the pandemic interrupted so many vital services needed for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer on a global level, it will take time to fully capture and analyze the data.

For example, we published a study from some 49 breast-certified centers in Europe looking at screening programs during the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that in those certified centers, around 20% of the patients will have an increase in the stage of cancer when they come to see us. That’s a big number, and it’s important to note these data are from just one study of breast cancer. My concern is that we haven’t spent enough time and energy gathering and sharing data to prepare for another global health crisis.

Furthermore, I’m not sure whether institutions and governments fully realize the impact COVID-19 had on the health workforce. We do see increased levels of burnout among cancer care specialists, so I’m disappointed that 3 years after the COVID-19 pandemic, we don’t see enough efforts taken to solve this very crucial issue.

What’s at stake here is public health globally. Therefore, national governments, professional societies, and hospitals should enact proactive policies and provide critical leadership and funding for burnout prevention programs. On the European level, I think the European Commission has a plan to begin addressing some of the issues related to COVID-19–induced stress on workers and systems, which is a good start. But we need to accelerate those efforts before it’s too late.

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Rubio has received honoraria from AstraZeneca and MSD.