Don S. Dizon, MD, FACP, FASCO, Director of Pelvic Malignancies Program at Lifespan Cancer Institute and Director of Medical Oncology at Rhode Island Hospital was born and reared in Guam. He also is Professor of Medicine and Professor of Surgery at Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island.

“I am the only son of a family of five children. My inspiration to become a doctor was through the television show St. Elsewhere. There was a scene where a resident had a difficult patient encounter, which was followed with an even more difficult conversation with his attending, who was quite critical of him. I remember the resident crying in the hallway about what had happened, and for some reason, it resonated with me,” said Dr. Dizon.

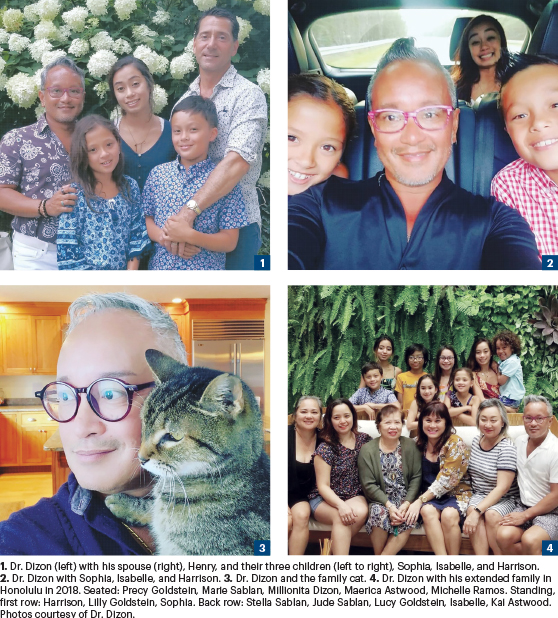

DON S. DIZON, MD, FACP, FASCO

TITLE

Director of Pelvic Malignancies Program, Lifespan Cancer Institute; Director of Medical Oncology, Rhode Island Hospital; Professor of Medicine and Professor of Surgery, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island

MEDICAL DEGREE

MD, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, New York

ON BEGINNING HIS CAREER AT MSK

“Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) ended up being my most memorable interview. I spoke with Dr. George Bosl, Chair of Medicine at the time. Naturally, I was nervous, but my apprehension didn’t last long, as Dr. Bosl’s demeanor put me at ease. Without saying it, Dr. Bosl let me know that at MSK, oncology was much more than treating cancer; it was a multidisciplinary holistic approach of care that was patient-centered. I knew MSK would be a great place to begin my career.”

Although Dr. Dizon’s parents applauded his determination, they were also concerned about the long path to a career in medicine. “My parents were worried that medicine was a very hard road, so they encouraged me to volunteer at the hospital in Guam. I did volunteer work in the emergency room at Guam Memorial Hospital before I went to college. And then in college, my passion for medicine did not waiver. However, when I entered the University of Rochester for my undergraduate work, I wasn’t sure I could get into medical school, simply because I don’t test well. The college experience allowed me the opportunity to explore other fields, and I fell in love with English literature and religious studies, so should medicine not work out, I was going to be okay because I had other passions to explore,” he explained.

The Imposter Syndrome

After completing his undergraduate work, Dr. Dizon applied to several medical schools but eventually decided to remain at the University of Rochester for his medical school training. Even though it was familiar ground, Dr. Dizon recalls feeling out of place as he took the initial steps of his medical career.

“When I walked into my first class of 100 medical students, it was this sense that I should not be there. The imposter syndrome—a psychological occurrence in which people doubt their skills, talents, or accomplishments and have a persistent internalized fear of being exposed as frauds—was significant to me. And I do remember, Cynthia Brown, a Black student in my class who saw the look on my face, and said: ‘No, we all belong here. You belong here, so we sit down.’ It was fantastic. She made me feel welcome and eased my sense of insecurity,” he related.

Asked what circumstances or persons influenced his decision to become an oncologist, Dr. Dizon responded: “As a third-year student at Strong Memorial Hospital, my first rotation was in obstetrics and gynecology. I fell in love with the field and got to do a surgery with the GYN oncologist at Rochester to remove a pelvic mass. I was just blown away by the complex operative field they were working in. The female pelvic anatomy was just so fascinating to me that I thought I wanted to be a surgeon and do gynecologic oncology. But in that same rotation, I had the experience of having pregnant women not want me in their delivery room. At the time, I felt I could not go through a residency and deal with that kind of rejection: not only because it’s a stranger coming into the delivery room, but it was a man coming into the delivery room. And so that convinced me not to do obstetrics and gynecology.”

The Decision Is Made: Oncology

According to Dr. Dizon, it was a patient’s sudden death that ultimately rebooted his interest in oncology, a decision he never looked back on. “When I went into my medicine rotation at Rochester, one of my first patients was an elderly gentleman with a new diagnosis of leukemia. I got to know him and his family. Then one day, I came into the hospital, and he wasn’t there; he had died suddenly overnight. What I remember was feeling the grief of not only not being there for this person I had followed and had come to know on a personal level when he died, but also the grief of knowing I wasn’t going to see his family again because I had gotten very close to them,” he recalled.

Dr. Dizon noted that his career-altering clinical experience was more than 20 years ago, at a time when treatment options for patients with acute leukemia were few and largely ineffective. “In fact, I remember the only options were very toxic chemotherapies. That was the moment I thought oncology might be a good field because there was so much that could be done. Since I was raised in the South Pacific, in a culture that saw death as a part of life, it did not scare me. I thought if I could be present in those tough doctor-patient conversations and provide hope and clarity, I could help people face the end of their lives,” he added.

A Memorable Interview at MSK

During his third year of residency at Yale New Haven Hospital, it was time to apply for fellowships, a process weighted with enormous career consequences. “I applied across the country, not sure where I was going to go. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) ended up being my most memorable interview. I spoke with Dr. George Bosl, Chair of Medicine at the time. Naturally, I was nervous, but my apprehension didn’t last long, as Dr. Bosl’s demeanor put me at ease. Remarkably, he didn’t ask me pointed questions about biology or chemistry or even my career goals. What he really wanted to know was who I was as a person and what were the most memorable clinical experiences I’d had and how those encounters shaped my approach to caring for patients with cancer. Without saying it, Dr. Bosl let me know that at MSK, oncology was much more than treating cancer; it was a multidisciplinary holistic approach of care that was patient-centered. The interview with Dr. Bosl was remarkable. I knew MSK would be a great place to begin my career,” he commented.

Elation and Insecurity

Matching into an oncology fellowship is extremely competitive. In many cases, the interview process is the determining factor of whether an applicant is accepted, which seems to have been the case with Dr. Dizon.

“When I was accepted into the MSK fellowship program, I was very excited at first, but again, the underlying feeling that they made a mistake was there,” he continued. “I think my training at MSK not only put me in connection with people who would become leaders in our field—Arti Hurria, Jake Dupont, Renier Brentjens, to name several—but it taught me you could be a researcher and a humanist at the same time. MSK is where I found I could still be a gynecologic oncologist with a medical oncology background, and I embraced that. I worked under Drs. David Spriggs and Carol -Aghajanian as my mentors, and Dr. Paul Sabbatini was also a huge influence on how I ended up setting up my own practice. They informed the way I talk with those I treat,” he said.

A New Career Path Emerges

During his fellowship, Dr. Dizon met Dr. Michael Krychman, who ran the center’s sexual health clinic and later served as Co-Director of the Sexual Medicine and Rehabilitation Program at MSK. “Dr. Krychman and I would chat about people we both had seen. And we ended up writing a case report about the toxicities of liposomal doxorubicin on the female genital area. It was a first report of its kind. I stayed at MSK for a little bit doing phase I clinical trial work and working in gynecologic oncology. However, when I had my first child, a daughter, my partner and I decided it was time to move where our family were and ended up in Providence, Rhode Island, at Women and Infants Hospital with Dr. Cornelius O. ‘Skip’ Granai,” he said.

After leaving MSK and his work with Dr. Krychman, Dr. Dizon saw a large unmet need in female sexual health after chemotherapy. “I remember going to Skip and asking if he would let me start a sexual medicine and rehabilitation program. And the first question he had was not how are you going to bill for it but how are you qualified to run this? So that forced me to do some self-inspection. I decided to go back as a sex educator and completed a course at Planned Parenthood, where I was the only physician. But that professional learning experience was fantastic for me. And Skip let me start that clinic, which we call the Center for Sexuality, Intimacy, and Fertility,” he noted.

Dr. Dizon continued: “And I worked with a gynecologist, Dr. Doreen Wiggins, to start that program. We published our first papers about how gynecologic oncologists, although well equipped to discuss sexuality, were not having these conversations, largely because of cultural bias and time constraints. When I was recruited back to Rhode Island Hospital, I started the Oncology Sexual Health First Responders Program, which is for colleagues who can look to our clinic as the first place they can turn to.”

A Slow Roll-Out of Programs

Asked how the mission to integrate sexual health issues into mainstream oncology was going, Dr. Dizon said: “Well, it’s been slow. We are still multiple steps back when it comes to offering resources related to sexuality compared to where we are in oncofertility. That said, I’m encouraged by the small steps people have taken to learn about the field and then to start their own programs. And my only request when I do talks on sexual health is that my colleagues who are touching people with cancer make it a point to at least allow for the conversation. And I think that’s really what it comes down to.”

A Closing Thought

Asked to share a closing thought with readers of The ASCO Post, Dr. Dizon responded: “When I was starting out as an attending, I heard from multiple people that the pathway to full professor should be narrow in focus so become an expert in a specific area. And I think that was true traditionally, but looking back on my own career, I followed my passions. If it was something I believed in, I pursued it. I continue to do research in gynecologic oncology, but along the way, I developed a specialty in sexual health after cancer. And then, I developed an interest in the use of social media in oncology as a basis as well.”

Dr. Dizon continued: “I’m very grateful that ASCO has always supported us and our work. More recently, I’ve become attuned to the disparities in cancer care and cancer outcomes for the LGBTQ community. To that end, I started to advocate on behalf of diversity in access to clinical trials, equity in accessing services, and helping the LGBTQ community to identify themselves through sexual orientation and gender identity questions. That work has sort of informed what I’m doing now with SWOG, where I have been named Vice Chair for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, as well as professional integrity. I’m excited to see what we can do in terms of those initiatives. And I’m grateful the American Cancer Society afforded me the opportunity to become an editor of CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. I would advise all young people entering this field to find a passion and follow it. That path might not always be the easiest, but in the end, it will be the most rewarding.”

Decompression Time

How does a super busy oncology innovator decompress? “That’s where my writing comes in because it is a discipline that requires a certain kind of concentration that I find therapeutic. And certainly, ASCO supported my online writing through ASCO Connection for a very long time. I appreciate that opportunity to reflect on things in the clinic. But in addition to that, I am an avid knitter. And I’m working on a sweater as we speak. I enjoy social media as a link between who I am professionally and personally. Naturally, being the father of a young child is transportive. So, despite the stressors of a very challenging career, I have a rich life out of work, which keeps things in perspective. And I love what I do in the world of oncology, so that’s a huge plus.”