In patients with intermediate- to high-risk smoldering multiple myeloma, treatment with single-agent lenalidomide, vs observation, led to a 72% reduction in the risk of disease progression at 3 years.1 Results of the phase III E3A06 study were presented at a press briefing in advance of the 2019 ASCO Annual Meeting by Sagar Lonial, MD, FACP, of Emory University, Atlanta.

“We showed, in the largest randomized study to date in smoldering myeloma, that we can prevent the development of symptomatic myeloma in a significant fraction of patients,” Dr. Lonial said. More than 90% of the intervention group remained progression-free at 3 years, he reported.

We don’t know that a true treatment strategy makes a difference, but we’ve shown that intervention can make a difference.— Sagar Lonial, MD, FACP

Tweet this quote

Although patients with smoldering multiple myeloma—an early, asymptomatic entity lacking the presence of CRAB criteria (elevated calcium, renal failure, anemia, bone lesions)—are typically monitored and not treated, some researchers have questioned whether early intervention could improve outcomes and even cure the disease before its full impact is felt.

“There’s no question that patients with multiple myeloma need immediate treatment to reverse evidence of organ damage, but a challenge we’ve struggled with is trying to identify patients without organ damage who are at highest risk of disease progression, and trying to intervene,” Dr. Lonial said.

Patients classified as having smoldering disease generally have a risk of disease progression of about 10% per year. After 5 years, approximately half of these patients will have symptomatic disease, he said.

Previous Findings by Spanish Myeloma Group

The study builds upon earlier work by The Spanish Myeloma Group, who reported in the smaller 2015 PETHEMA trial that lenalidomide/dexamethasone improved progression-free and overall survival, vs observation, in patients at high risk of disease -progression.2

That study, however, was criticized in ways that were avoided by the current study design: patients were not screened with advanced imaging techniques; investigators applied an outdated definition of high risk; and the regimen included dexamethasone, making it impossible to isolate the effect of lenalidomide, he said.

“The fact that the study did not use modern imaging [to screen for eligibility] is important, because patients with negative x-rays may have bone disease by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or positron-emission tomography (PET) scan,” Dr. Lonial noted. “In our study, we required MRI before study entry to be sure we were not enrolling patients who already had myeloma, which was the main criticism of the Spanish trial.”

E3A06 also eliminated dexamethasone, which can suppress or eliminate the malignant clone and produce a temporary response, as opposed to control the clone, as was the aim of using single-agent lenalidomide, he said.

The previous trial, therefore—while considered important—did not change the standard of care, “but now,” he said, “with the E3A06 trial, in aggregate with the PETHEMA trial, many of us would argue that early intervention with a prevention strategy can reduce the risk of conversion to symptomatic myeloma.”

E3A06 Details

E3A06 was a randomized phase III intergroup trial that tested the effect of single-agent lenalidomide compared with observation in patients classified as having intermediate-risk or high-risk smoldering myeloma. Eligibility required ≥ 10% plasma cells and abnormal serum free light chain ratio (< 0.26 or > 1.65).

In an initial phase II run-in phase, 44 patients received lenalidomide to demonstrate safety. In the phase III trial, 182 patients were randomly assigned to either lenalidomide (25 mg/d for 21 of 28 days) or observation. Baseline characteristics were similar between the arms. Median follow-up was 71 months for the phase II portion and 28 months for phase III. The primary endpoint was progression-free survival.

Significant Reduction in Risk of Progression

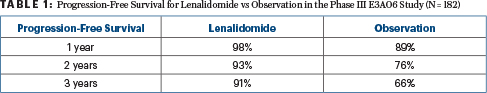

At 3 years, 87% of the phase II cohort, all of whom received lenalidomide, were progression-free, as were 78% at 5 years. For the phase III comparison, the 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year progression-free survival rates were 98%, 93%, and 91% for lenalidomide vs 89%, 76%, and 66%, respectively, for observation (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.28; P = .0005), as shown in Table 1. The overall response rate with lenalidomide was 47.7% for the phase II study and 48.9% for the phase III, with no responses seen in the observation arm.

Interestingly, when broken down into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups, each subset was found to benefit “almost equally” from early intervention. “This suggests that while high-risk patients may be the ones we target now, a fertile area of further investigation may be the intermediate group, for whom no trial has yet shown benefit in preventing symptomatic disease. We do see a benefit for the intermediate-risk patients, but the overall survival follow-up is too short to say these patients should all be treated,” he concluded.

Low–intermediate-risk patients were enrolled when the study loosened eligibility criteria for only slightly abnormal free light chain ratios. Although they, too, derived benefit, this is not a group to consider for treatment at this time, he added.

Adverse Events

Grade 3 to 4 nonhematologic toxicities were observed in approximately 28% of patients, and grade 3 to 4 hematologic toxicity (primarily neutropenia) in about 6%. The cumulative incidence of invasive secondary primary malignancies was 5.2% for lenalidomide and 3.5% for observation.

There were no differences in quality-of-life scores between the arms. However, 80% of patients in phase II and 51% in phase III discontinued lenalidomide.

Looking Ahead

A preventive strategy for smoldering myeloma is likely to be less intensive than the treatment strategies employed for symptomatic disease, he said. “We are focusing on enhancing immune surveillance of the existing malignant clone and preventing that clone from progressing, as opposed to eradicating the disease, which is the goal of treatment,” Dr. Lonial said.

Ongoing studies are, in fact, pursuing more aggressive interventions, such as combining lenalidomide, dexamethasone, and daratumumab, or other new active agents. Other studies are evaluating the benefit of induction therapy, consolidation, transplant, and 2 years of maintenance in smoldering disease, he said.

“We don’t know that a true treatment strategy makes a difference, but we’ve shown that intervention can make a difference,” he said. “Now is the time to explore other ideas, with more intensive regimens and with a different focus.” ■

DISCLOSURE: Dr Lonial has consulted or advised for Celgene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen Oncology, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Amgen, AbbVie, Takeda, Merck, and Juno Therapeutics; and has received research funding from Celgene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Takeda.

REFERENCES

1. Lonial S, Jacobus SJ, Weiss M, et al: E3A06: Randomized phase III trial of lenalidomide versus observation alone in patients with asymptomatic high-risk smoldering multiple myeloma. 2019 ASCO Annual Meeting. Abstract 8001. To be presented June 2, 2019.

2. Mateos M-V, Hernandez M-T, Giraldo P, et al: Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for high-risk smoldering multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 369:438-447, 2013.