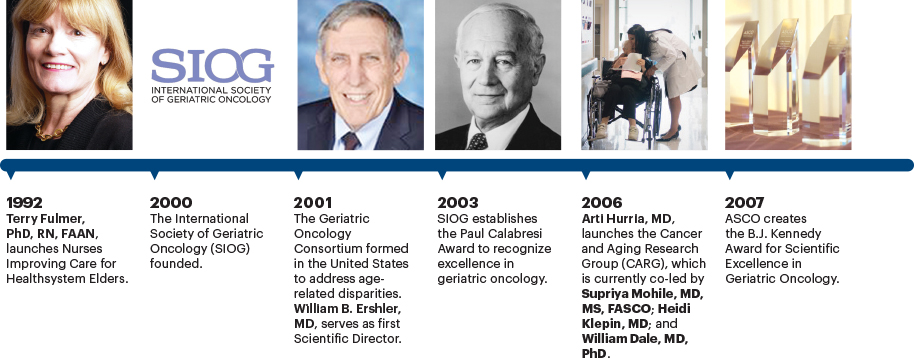

In part 1 of this three-part article, which was published in the October 10, 2020, issue of The ASCO Post, we chronicled the progress made in geriatric oncology up to the decade of the 1990s, which saw an explosion of research activity in the study of aging and cancer. In part 2, we review the activity in the field over the following 25 years. This period started with the founding of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) in New York in 2000, during the International Conference of Geriatric Oncology. We also look back to the 1990s with the evolution of geriatric oncology nursing, which will be discussed briefly herein and in greater detail in part 3.

Silvio Monfardini, MD

Lodovico Balducci, MD

Janine Overcash, PhD, APRN-CNP, FAANP, FAAN

Matti S. Aapro, MD

The first president of the organization was Paul Calabresi, MD, an international authority on the pharmacology of anticancer agents, a founding member of Brown Medical School, and ASCO President from 1969 to 1970. Dr. Calabresi was among the first medical oncologists to recognize the prominence of cancer in the elderly and study the effects of cytotoxic chemotherapy in older patients.

SIOG’s other founding members include three authors of this paper, Matti S. Aapro, MD; Lodovico Balducci, MD; and Silvio Monfardini, MD; as well as Gilbert B. Zulian, MD; Lazzaro M. Repetto, MD, PhD; Martine Extermann, MD, PhD; John M. Bennett, MD; and Riccardo A. Audisio, MD.

The organization was founded on several principles and goals to advance the study of cancer and aging, including:

- Providing an international forum for clinical and basic scientists, as well as other professionals, such as social workers and dietitians, involved in the study of cancer in older adults

- Issuing and updating consensus guidelines related to the management of older patients with cancer

- Promoting educational activities, both nationally and internationally

- Exploring practical ways to weave together oncologic and geriatric expertise by promoting multidisciplinary care

- Liaising with professional societies, including ASCO, the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR), and the American Geriatrics Society (AGS).

Since its inauguration, SIOG has accrued more than 1,900 members from 43 countries; it currently has 365 active members. Annual conferences are usually held in Europe or the United States. Other major achievements include the following:

- In 2003, SIOG established the Paul Calabresi Award, which recognizes a prominent expert in geriatric oncology; in 2017, the SIOG Lifetime Achievement Award was created.

- In 2004, SIOG issued its first guideline on the surgical management of older patients. Since then, the organization has issued 37 guidelines on specific tumors, geriatric assessment, and supportive care.1

- In 2010, SIOG launched the Journal of Geriatric Oncology, an international, multidisciplinary journal focused on advancing research in the pathogenesis, biology, treatment, and survivorship concerns of older adults with cancer.

SIOG currently has several working groups, including the Young SIOG Interest Group, which includes young clinicians and researchers working in the field of geriatric oncology; the Nursing and Allied Health Interest Group, which was established by nurses and allied health professionals working in the field of geriatric oncology; the ESMO/SIOG Cancer in the Elderly Working Group; and the SIOG COVID-19 Working Group.

The most significant events of this period can be reported as follows.

Federal Grants to Support Research and Clinical Programs in Geriatric Oncology

In 2005, the National Institutes on Aging (NIA) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) partnered to support clinical and basic research, as well as clinical programs, in geriatric oncology within the NCI-designated cancer center system. This effort was spearheaded by Rosemary Yancik, PhD, who had been among the first to bring attention to the magnitude of the cancer burden on aging Americans and the need for the establishment of the field of geriatric oncology. Dr. Yancik, a medical sociologist, served for many years at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in both the NIA and the NCI. During her tenure at the NIH, Dr. Yancik organized meetings with researchers interested in the study of cancer in the elderly.

The first step of this cooperative effort was a conference in Bethesda, Maryland, attended by the directors of the 39 cancer centers that were NCI-designated at the time, requests for proposals and programs dedicated to research in geriatric oncology sprouted from this meeting. The importance of this event in moving the field forward cannot be overestimated. For example:

It laid the foundation for ongoing research cooperation among the institutes at the NIH. One important recent consequence of this cooperation was a combined conference, in 2018, of extramural and intramural scientists from the NIA and the NCI on cancer in older patients, to define a research agenda for the next decade. Luigi Ferrucci, MD, Scientific Director of the NIA, referred to the event as “a dream team collaboration on cancer in aging.”

It established geriatric oncology programs throughout comprehensive cancer centers. As a result, many cancer centers now have geriatricians working alongside oncologists in the care of elderly patients and have sponsored research conferences and symposia on geriatric oncology.

The conference also sparked the investigation of novel methods to study cancer and aging beyond the classical clinical trial design, including the assessment of life expectancy and tolerance of treatment based on geriatric assessment and the use of rapid-learning databases to assess the outcome of patients who were ineligible for clinical trials.

It also led to the identification and correction of biases within NCI grant proposal review committees that had prevented funding of deserving proposals in geriatric oncology.

The BJ Kennedy Award for Scientific Excellence in Geriatric Oncology

Created by ASCO in 2007 in Honor of Byrl James “B.J.” Kennedy, MD, 1987–1988 ASCO President, the BJ Kennedy Award for Scientific Excellence in Geriatric Oncology recognizes members who have made outstanding contributions to the research, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer in the elderly and in bringing an understanding of geriatric oncology to fellows and junior faculty. This award might be considered a milestone because with its creation, ASCO acknowledged the legitimacy and the need of the geriatric oncology movement by rewarding clinical investigators in the field. Naturally, this award has contributed to the spreading of the geriatric oncology culture within the oncology community and motivated young investigators to enter the field:

SIOG Treviso Advanced Course

The launch of the SIOG Treviso Advanced Course, originally supported by the Catholic University School of Medicine in Rome and SIOG, was the brainchild of Dr. Monfardini and geriatrician Giuseppe Colloca, MD, and inspired by the principles of Roberto Bernabei, MD, Chief of Geriatrics at the Catholic University School of Medicine. Undoubtedly, Dr. Bernabei’s novel vision of geriatrics influenced the development of the field of geriatric oncology.

The Treviso Advanced Course was also supported by Dr. Balducci and represented a novel attempt to have geriatricians and oncologists work together. The program offers a successful model for the development of a dialog between geriatricians and oncologists and was endorsed enthusiastically by all the participants. Two years after its inception, the number of applications overwhelmed participation availability, and it became necessary to organize similar courses in other countries, including Australia and Brazil.

Advancement in Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment

Unsurprisingly, the comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA), which is used to assess the status of older people, has been the focus of many geriatric oncology studies. During the ASCO20 Virtual Scientific Program, four such studies were presented that should be practice-changing and provided irrefutable evidence that the quality of life of older patients can be improved by reducing treatment toxicity.2-5 Over the past 2 decades, CGA studies have focused on two main areas: clinical application and the development of screening tests capable of identifying patients who need a comprehensive geriatric assessment.

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment Classification: In 2000, Balducci et al6,7 proposed classifying older individuals into fit, vulnerable, and frail categories, based on their geriatric assessment, to guide the selection of cancer treatment. According to this classification system, fit patients could receive full-dose treatment, frail patients would mainly receive symptom management, and vulnerable patients would be treated with special precautions and, when possible, rehabilitation.

This approach was the first attempt to treat cancer in the elderly based on geriatric assessment. It received worldwide application and demonstrated utility in some clinical trials. Tucci et al showed that frail patients with large cell lymphoma benefited more from reduced doses of chemotherapy than full doses.8

Today, this classification has only historical interest for several reasons. It was a commonsense classification not based on clinical data, and the definition of frailty is obsolete.9 Indeed, the definition of frailty is still controversial.

In 2002, Repetto et al10 confirmed the previous observations that the CGA provided additional information on the fitness of older patients with cancer. In 2012, Puts et al published the first systematic review of geriatric assessment in older adults in oncology11; it included 73 studies on the topic and found that geriatric assessment might take as little as 10 minutes or as long as 45 minutes. Specific domains of the geriatric assessment were associated with an increased risk of therapeutic toxicity and mortality. In two studies, the authors found that geriatric assessment had impacted as many as 50% of clinical decisions. Two years later, the authors updated their review in the Annals of Oncology with an evaluation of 34 additional studies.12

Undoubtedly, a major development of the CGA has been the construction of two instruments capable of predicting the risk of chemotherapy-related toxicity in patients aged 65 years and older with solid tumors and lymphomas. The Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH) score13 and the Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG) instrument14 were developed with the cooperation of different institutions, and the CARG instrument was validated within the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB).15 This information demonstrated the feasibility of cancer research based on the estimate of functional age within a major cooperative group. These studies should be considered landmarks and groundbreaking in the field.

Predicting the Risks of Chemotherapy Complications: Other Methods to predict the risk of chemotherapy complications based on the geriatric assessment have been proposed and deserve mention—for example, the Elderly Cancer Patients (ELCAPA) survey, which collected prospective information on a cohort of patients aged 70 and older in France.16 The authors were able to define four different patient profiles at different risks of death, chemotherapy-related complications, and hospital readmissions.

Other studies used the geriatric assessment tool to predict early mortality.17,18 Also of historical interest is the development of two models used to estimate long-term mortality (up to 14 years) for older individuals living in the community.19,20 These models were published in the general geriatric literature and are widely used by geriatric oncologists to estimate the potential risks and benefits of cancer chemotherapy.

The benefits of geriatric assessment were also established in hematologic malignancies other than lymphoma. Palumbo et al21 subdivided 869 patients with multiple myeloma aged 65 and older undergoing three different clinical trials into three categories: fit, nonfit, and frail, based on geriatric assessment and a different risk of therapeutic toxicity and mortality. Klepin et al22 demonstrated that in patients aged 60 and older diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia, physical and cognitive functions were predictors of survival. The geriatric assessment tool demonstrated that age was a risk factor for the development of disability after chemotherapy.23,24

Studies have shown that geriatric assessment might have revealed as many as 70% of non–cancer-related interventions that were necessary for the wellness of older individuals. This area is still underdeveloped and is an extremely important focus of future investigations.

Benefit of a Shortened Geriatric Assessment: A main concern of the utilization of the CGA is the time it takes to complete the test. Several investigators have explored the value of using a shortened assessment to identify individuals in need of full assessment.

In preparing the ASCO Guideline for Geriatric Oncology, Mohile et al25 conducted a systematic review of the medical literature. These authors recommended that clinicians use instrumental activities of daily living to assess patient function; a thorough history or validated tool to assess comorbidity; a single question for falls; the Geriatric Depression Scale to screen for depression; the Mini-Cog or the Blessed Orientation-Memory-Concentration test to screen for cognitive impairment; and an assessment of unintentional weight loss to

evaluate nutrition. In addition, the guideline recommends either the CARG or CRASH tool to obtain estimates of chemotherapy toxicity risk and the Geriatric-8 or Vulnerable Elders Survey–13 to help predict mortality.

Birth of the Cooperative Groups

In 2001, the Geriatric Oncology Consortium (GOC) was formed in the United States, with the mission of addressing age-related disparities in cancer research, education, and treatment. The first Scientific Director of the GOC was William B. Ershler, MD, and the Executive Director was Jody Simon, RPh. The main scientific product of the GOC before it merged into the CARG was a randomized controlled study of supportive care with pegfilgrastim in older patients receiving chemotherapy.26

Other important groups include the following:

- The French Geriatric Oncology Group, created in 2002, is supported by the Unicancer hospital network system in France and is dedicated to cancer care in the elderly.

- The CARG was founded in 2006 by the late Arti Hurria, MD, and is currently co-led by Supriya Mohile, MD, MS, FASCO; Heidi Klepin, MD; and William Dale, MD, PhD. The mission of the CARG is to foster collaboration among all clinical investigators in geriatric oncology research. Its goals include reliably assessing older patients at highest risk for adverse outcomes from cancer and its treatments; developing effective interventions to improve outcomes for vulnerable older adults and their caregivers; mentoring the next generation of geriatric cancer researchers; and disseminating research findings widely to inform clinical practice.

- The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Cancer in the Elderly Task Force (ETF) was founded in 2015 with the aim of developing, conducting, coordinating, and stimulating research on elderly patients with cancer. Following the CALGB model created in 1995, the ETF established close interactions with disease-oriented committees. Since its inception, the scope of activity of the ETF has included a common language within EORTC to account for the diversity in the older population of patients, to establish a rapid-answer database and the development of specific clinical trials in elderly patients.

Guidelines for the Treatment of Older Adults With Cancer

As mentioned earlier, SIOG has issued 37 guidelines in the management of older patients with cancer. In addition, the following guidelines represent important progress in the care of older patients:

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Senior Adult Oncology, version 2.2014.27

- ASCO Guideline for Geriatric Oncology,25 which prompted the acceptance of geriatric assessment as a clinical instrument by practicing oncologists throughout the world.

Some Examples of Research Advances in Cancer Care Management in Elderly Patients

The following studies highlight important milestones in the management of older adults with cancer:

2002—Coiffier et al28 reported that the combination chemotherapy regimen of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) was superior to CHOP alone in patients aged 65 or older and diagnosed with large B-cell lymphoma.

2004—Two cooperative groups reported the results from randomized controlled trials demonstrating that docetaxel prolonged the survival of patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. These seminal studies paved the way for a number of clinical trials investigating chemotherapy and hormone therapy in older patients with different stages of prostate cancer.29,30

2011—Quoix et al reported that combination chemotherapy was superior to single-agent treatment in older fit individuals with non–small cell lung cancer. All the patients in the study had undergone a geriatric assessment prior to their recruitment into the trial.31

2014—Goede et al reported that the combination of obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) was superior to chlorambucil alone, in terms of both disease-free and overall survival.32 The historical significance of this study cannot be overstated, since it demonstrated for the first time an improvement in overall survival in older patients with CLL and inaugurated a series of randomized studies in older patients evaluated with a geriatric assessment.

Advent of Geriatric Oncology Nursing

The field of geriatric oncology nursing is a merger of two disciplines that combined to meet the complex needs of older people with cancer. An essential premise of geriatric health care is the use of disciplinary medical teams that include nurses, physicians, social workers, pharmacists, dietitians, physical therapists, and chaplains to address age-related needs of older patients.33

During the 1980s in the United States, multidisciplinary teams were conducting geriatric evaluation in hospitals and long-term care settings that included nurses in the role of direct patient care.34,35 A form of comprehensive geriatric assessment was first proposed in the late 1930s.36 It has evolved into what is known today as comprehensive geriatric assessment, was adopted by the National Institutes of Health in 1987,36 and has been integrated into oncology. The use of multidisciplinary medical teams conducting comprehensive geriatric assessment in geriatric oncology was the catalyst for the establishment of the field of geriatric oncology nursing.

Important Milestones in the Evolution of Geriatric Oncology Nursing

1980s—In 1988, the Oncology Nursing Society recognized the need for specialty nursing care for older patients and established a Gerontology/Oncology Focus Group to promote networking among members with an interest in the care of older adults with cancer.37

1992—Nurses Improving Care for Healthsystem Elders was founded by Terry Fulmer, PhD, RN, FAAN, who wanted to improve education for nurses working in health-care facilities in the United States and Europe.38

1996—The Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing (HIGN) at New York University’s Rory Meyers College of Nursing was founded to support nursing students, faculty, and nurses at all levels of care. Many of the providers trained by the HIGN are focused on oncology nursing and are associated with academic medical centers to advance gerontology practice and research in caring for older adults with complex needs.39

Also in the 1990s, geriatric oncology ambulatory care clinics were developed to adequately treat older patients with cancer.40 The role of geriatric oncology nurses has grown over the decades, and they now have a voice in the development of programs in geriatric oncology for organizations such as ASCO, SIOG, the Gerontological Society of America, the NCCN, and the EORTC.

Today, the practice of geriatric oncology nursing continues to develop and evolve to meet the needs of older people with cancer in health-care settings worldwide. In summary, the nursing profession is particularly attunned to unraveling and managing the complexity of aging and cancer, and nurses are at the forefront of developing geriatric expertise in cancer care. [Editor’s note: See the next issue of The ASCO Post for more about the important role of geriatric oncology nursing in the history of geriatric oncology.]

Conclusion

The aim of chronicling this history was to describe the efforts of many people over the almost 40 years that led to the development of the field of geriatric oncology. Among the main accomplishments of these pioneers was overcoming ageism in the management of cancer. Another was the shift of focus of care from the relatively simple approximation of the disease to the complex reality of each patient. The unraveling of this complexity required the contribution of professionals from various oncology specialties, geriatricians, nurses, dietitians, and social workers.

Purposefully, we did not address the question of whether geriatric oncology should be considered another subspecialty of oncology, because a definite answer does not appear possible at this moment. Irrespective of whether geriatric oncology should be considered a specialty, a task force, or both, the construct of geriatric oncology is dynamic and congruous with the new developments of our understanding of both cancer and aging.

DISCLOSURE: The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Dubianski R, Wildes TM, Wildiers H: SIOG guidelines—Essential for good clinical practice in geriatric oncology. J Geriatr Oncol 10:196-198, 2019.

2. Qian CL, Knight HP, Ferrone CR, et al: Randomized trial of a perioperative geriatric intervention for older adults with cancer. ASCO20 Virtual Scientific Program. Abstract 12012.

3. Soo WK, King M, Pope A, et al: Integrated geriatric assessment and treatment (INTEGERATE) in older people with cancer planned for systemic anticancer therapy. ASCO20 Virtual Scientific Program. Abstract 12011.

4. Li D, Sun CL, Kim H, et al: Geriatric assessment-driven intervention (GAIN) on chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: A randomized controlled trial. ASCO20 Virtual Scientific Program. Abstract 12010.

5. Mohile SG, Mohamed MR, Culakova E, et al: A geriatric assessment intervention to reduce treatment toxicity in older patients with advanced cancer: A University of Rochester Cancer Center NCI community oncology research program cluster randomized clinical trial. ASCO20 Virtual Scientific Program. Abstract 12009.

6. Balducci L, Beghe C: The application of the principles of geriatrics to the management of older patients with cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 35:147-154, 2000.

7. Balducci L: Evidence-based management of cancer in the elderly. Cancer Control 7:368-376, 2000.

8. Tucci A, Ferrari S, Bottelli C, et al: A comprehensive geriatric assessment is more effective than clinical judgment to identify elderly diffuse large cell lymphoma patients who benefit from aggressive therapy. Cancer 115:4547-4553, 2009.

9. Balducci L: Frailty: A common pathway in aging and cancer. Interdiscip Top Gerontol 38:61-72, 2013.

10. Repetto L, Fratino L, Audisio RA, et al: Comprehensive geriatric assessment adds information to Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status in elderly cancer patients: An Italian Group for Geriatric Oncology Study. J Clin Oncol 20:494-502, 2002.

11. Puts M, Hardt J, Monette J, et al: Use of geriatric assessment for older adults in the oncology setting: A systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst 104:1133-1163, 2012.

12. Puts MT, Santos B, Hardt J, et al: An update on a systematic review of the use of geriatric assessment for older adults in oncology. Ann Oncol 25:307-315, 2014.

13. Extermann M, Boler I, Reich R, et al: Predicting the risk of chemotherapy toxicity in older patients: The Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH) score. Cancer 118:3377-3386, 2012.

14. Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, et al: Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: A prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 29:3457-3465, 2011.

15. Hurria A, Mohile S, Gaira A, et al: Validation of a prediction tool for chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol 34:2366-2371, 2016.

16. Ferrat A, Audereau E, Paillaud E, et al: Four distinct health profiles in older patients with cancer: Latent class analysis of the prospective ELCAPA cohort. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 71:1653-1660, 2016.

17. Soubeyran P, Fonck M, Blanc-Bisson C, et al: Predictors of early death risk in older patients treated with first-line chemotherapy for cancer. J Clin Oncol 30:1829-1834, 2012.

18. Brunello A, Fontana A, Zefferri V, et al: Development of an oncological-multidimensional prognostic index (Onco-MPI) for mortality prediction in older cancer patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 142:1069-1071, 2016.

19. Cruz M, Covinsky K, Widera EW, et al: Predicting 10 year mortality in older adults. JAMA 309:874-876, 2013.

20. Schonberg MA, Davis RB, McCarthy EP, et al: External validation of an index to predict 9-year mortality of community dwelling adults 65 and older. J Am Ger Soc 59:1444-1451, 2011.

21. Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Mateos MV, et al: Geriatric assessment predicts survival and toxicities in elderly myeloma patients: An International Myeloma Working Group Report. Blood 125:2068-2074, 2015.

22. Klepin HD, Geiger AM, Tooze JA, et al: Geriatric assessment predicts survival for older adults receiving induction chemotherapy for acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood 121:4287-4294, 2013.

23. Shahrokni A, Wu AJ, Carter J, et al: Long-term toxicity of cancer treatment in older patients. Clin Geriatr Med 32:63-80, 2016.

24. Decoster L, Kenis C, Schallier D, et al: Geriatric assessment and functional decline in older patients with lung cancer. Lung 195:619-626, 2017.

25. Mohile SG, Dale W, Somerfield MR, et al: Practical assessment and management of vulnerabilities in older patients receiving chemotherapy: ASCO Guideline for Geriatric Oncology. J Clin Oncol 36:2326−2347, 2018.

26. Balducci L, Al-Halawani H, Charu V, et al: Elderly cancer patients receiving chemotherapy benefit from first-cycle pegfilgrastim. Oncologist 12:1416-1424, 2007.

27. Hurria A, Wildes T, Blair SL, et al: Senior adult oncology, version 2.2014: Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 12:82-126, 2014.

28. Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, et al: CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 346:235-242, 2002.

29. Petrylak DP, Tangen CM, Hussain MH, et al: Docetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 351:1513-1520, 2004.

30. Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, et al: Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 351:1502-1512, 2004.

31. Quoix E, Westeel V, Zalcman, et al: Chemotherapy in elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 74:364-368, 2011.

32. Goede V, Fischer K, Busch R, et al: Obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med 370:1101-1110, 2014.

33. Fulmer T, Flaherty E, Hyer K: The geriatric interdisciplinary team training (GITT) program. Gerontol Geriatr Educ 24:3-12, 2003.

34. Allen CM, Becker PM, McVey LJ, et al: A randomized, controlled clinical trial of a geriatric consultation team: Compliance with recommendations. JAMA 255:2617-2621, 1986.

35. Rubenstein LZ, Wieland D, English P, et al: The Sepulveda VA Geriatric Evaluation Unit: Data on 4-year outcomes and predictors of improved patient outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc 32:503-512, 1984.

36. Jiang S, Pingping L: Current development in elderly comprehensive assessment and research methods. Biomed Res Int 2016:3528248, 2016.

37. Bond SM, Bryant AL, Puts M: The evolution of gero-oncology nursing. Semin Oncol Nurs 32:3-15, 2016.

38. Fulmer T, Mezey M, Bottrell M, et al: Nurses Improving Care for Healthsystem Elders (NICHE): Using outcomes and benchmarks for evidence-based practice. Geriatr Nurs 23:121-127, 2002.

39. New York University Rory Meyers College of Nursing. Available at https://nursing.nyu.edu/innovation/hartford-institute-geriatric-nursing. Accessed October 12, 2020.

40. Overcash J: Integrating geriatrics into oncology ambulatory care clinics. Clin J Oncol Nurs 19:E80-E86, 2015.

Dr. Monfardini is Director of the Geriatric Oncology Program at Instituto Palazzolo, Fondazione Don Gnocchi, in Milan, Italy. Dr. Balducci is Professor of Oncology and Medicine at the University of South Florida College of Medicine and Chief of the Division of Geriatric Oncology, Senior Adult Oncology Program at H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute. Dr. Overcash is Professor of Clinical Nursing and Co-Director of the Academy for Teaching Innovation, Excellence, and Scholarship. Dr. Aapro is a Member of the Board, Genolier Cancer Center in Genolier, Switzerland, and of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) until September 2020.