I read with great interest the results from the phase II ZUMA-12 study of axicabtagene ciloleucel, presented during the 2020 American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting & Exposition.1 But the results raised several questions for me.

Syed Ali Abutalib, MD

Axicabtagene ciloleucel, an autologous anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on October 18, 2017, for the treatment of adults with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) after two or more lines of systemic therapy. The approved indications included diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) not otherwise specified, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, high-grade B-cell lymphoma, and DLBCL arising from follicular lymphoma.2 Earlier this year on March 5, 2021, the treatment received FDA approval for adults with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma (FL) after two or more lines of systemic therapy.3

According to the authors of this multicenter, open-label, single-arm study,1 this is the first clinical trial evaluating CAR T-cell therapy as a first-line treatment in patients with high-risk LBCL. Eligible subjects met two criteria for high-risk LBCL: (1) double- or triple-hit lymphoma by fluorescence in situ hybridization per investigator or LBCL with an International Prognostic Index (IPI) score ≥ 3; and (2) a positive interim fluorodeoxyglucose–positron-emission tomography (FDG-PET, defined as Deauville score [DS] 4 or 5), after two cycles of an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and an anthracycline-containing regimen. The patients underwent leukapheresis (≥ 2 weeks after prior systemic therapy) and optional nonchemotherapy bridging at the investigator’s discretion, followed by a conditioning chemotherapy regimen of cyclophosphamide at 500 mg/m2/d and fludarabine at 30 mg/m2/d for 3 days, and a single infusion of axicabtagene ciloleucel at a target dose of 2 × 106 CAR T cells/kg.

The primary endpoint was investigator-assessed complete response rate per Lugano classification. Key secondary endpoints included objective response rate, frequency of adverse events, and levels of CAR T cells and cytokines in the blood and serum. As of July 15, 2020, 31 patients have been enrolled and treated, and as of January 24, 2020, in a planned interim analysis, 15 patients were treated with axi-cel with at least 3 months of follow-up.1

The interim analysis of ZUMA-121 found that among 12 response-evaluable patients, the investigator-assessed overall response rate was 92% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 62%–100%), with a complete response rate of 75% (95% CI = 43%–95%), and 75% of patients had ongoing responses at data cutoff. Among 15 patients treated (safety analysis set), the investigator-assessed overall response rate was 93% (95% CI = 68%–100%), with a complete response rate of 80% (95% CI = 52%–96%), and 86% of patients had ongoing responses at data cutoff.

If we are switching a potentially curative anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and an anthracycline-containing regimen based on the assumption that interim FDG-PET2 is truly positive, then the term ‘front-line therapy’ is a misnomer.— Syed Ali Abutalib, MD

Tweet this quote

The most common grade ≥ 3 adverse events (≥ 25% of patients) were white blood cell count decrease (40%), anemia (27%), and encephalopathy (27%). Grade ≥ 3 cytokine-release syndrome and neurologic events occurred in 20% and 27% of patients, respectively. All adverse events were resolved by the time of the data analysis.

Is It a Front-Line Study or Not?

Question 1: If the assumption is that there is early failure in response to front-line therapy (based on abnormal interim FDG-PET2 [ie, FDG-PET after two treatment cycles]), meaning patient will not achieve a complete response, then how does one define next-line or subsequent therapy—still as front line?

Answer: If we are switching a potentially curative, anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and an anthracycline-containing regimen based on the assumption that interim FDG-PET2 is truly positive, then the term “front-line therapy” is a misnomer. In my opinion, it is also not classified as “consolidation,” as this would be the case if front-line autologous transplant was preplanned for patients with chemosensitive disease, but such is not the condition in ZUMA 12.1 I believe it is best to refer to this strategy as “early salvage” or “early second-line” therapy, which would still count as progress!

Question 2: Does a positive interim FDG-PET2 in newly diagnosed DLBCL always imply early treatment failure?

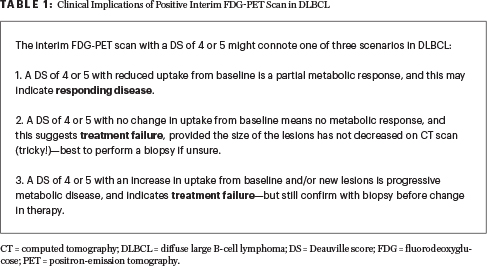

Answer: To date, the results of interim FDG-PET2 scan remains elusive and may imply types of responses other than early treatment failure in DLBCL (Table 1). A negative interim FDG-PET does carry a high negative predictive value (but is also not perfect).

There remain several barriers to recommending an interim FDG-PET scan in high-risk DLBCL. These barriers include the fact that there is no standard time for interim scanning (eg, after cycles 2, 3, or 4); the question of what constitutes a positive or negative FDG-PET scan, considering the high incidence of interreader disagreement; and whether there should be different values and/or methods used in the interim setting compared with those for pre- and posttreatment FDG-PET scan. Furthermore, many other variables such as cell of origin (ie, germinal center B-cell–like [GCB] vs non-GCB), timing of last chemotherapy, growth factor, inflammatory response, necrosis, and type of therapy used may lead to false-positive FDG-PET scan results.4-17

Interim Positive FDG-PET Scan and Biopsy

In a 2010 study by Moskowitz et al, interim FDG-PET scan did not identify patients at high risk for a poor outcome.4 The investigators reported on 97 patients with advanced-stage DLBCL, of whom 38 patients were deemed FDG-PET–positive after four cycles of accelerated R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone); however, only 5 patients (13%) had evidence of viable DLBCL in the biopsy specimen. On the contrary, two patients with a negative interim FDG-PET biopsy underwent a repeat biopsy at the conclusion of therapy, for persistent FDG-PET–positive disease at the same site; the repeat biopsy demonstrated active DLBCL. Thus, in these patients, interim biopsies likely missed the viable tumor. Sampling error is another concern.

To date, the results of interim FDG-PET2 scan remains elusive and may imply types of responses other than early failure in DLBCL.— Syed Ali Abutalib, MD

Tweet this quote

Most recently, a 2021 study by Tokola et al demonstrated a favorable prognosis for patients with positive interim FDG-PET who had negative biopsies.5 Moreover, a negative FDG-PET seems to be predictive in DLBCL, according to a large meta-analysis by Burggraaff et al published in 2019.18 This analysis included 19 studies and found a negative predictive value of 80% (range = 64%–95%). This systematic review also showed the challenges in positive interim FDG-PET cases, with the positive predictive value ranging widely from 20% to 74%.

Eligibility Criteria for Change of Therapy: What Is Missing?

Question 3: Does an IPI ≥ 3 in DLBCL accurately identify patients with an extremely dismal prognosis?

Answer: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is a heterogeneous set of diseases, with patients exhibiting a wide range of outcomes.19-22 In the study by Ziepert et al, the IPI score was highly significantly associated with the event-free survival, progression-free survival, and overall survival endpoints in patients treated with R-CHOP or R-CHOP–like chemotherapy regimens.20 For an IPI of 3, the 3-year estimates for event-free, progression-free, and overall survival were 53.2%, 58.6%, and 65.1%, and for IPI 4 and 5, they were 49.5%, 55.8%, and 59.0%, respectively.

Ruppert et al evaluated 2,124 patients with DLBCL treated with front-line R-CHOP or R-CHOP–like chemotherapy across seven multicenter randomized clinical trials. They showed 5-year overall survival estimates of 67% among patients with an IPI of 3 and 54% for those with an IPI greater than 3.22 These large data sets imply that a significant proportion of patients with a high IPI (≥ 3) are long-term survivors, and this score does not identify patients with an overall survival below 50%.

It would be useful to carefully identify new clinical, molecular, and imaging markers (other than the strategy used in ZUMA-12) that can better identify patients at high risk of early treatment failure in the rituximab era. Disappointingly, at the present time, such a prognostic model in patients with IPI ≥ 3 DLBCL does not exist.

Question 4: Are there any long-term double-hit lymphoma/triple-hit lymphoma survivors using the current front-line therapy of R-CHOP or its variant with or without radiation therapy (in limited-stage disease)?

Answer: Approximately 5% to 10% of DLBCL cases possess chromosomal rearrangements involving MYC, BCL2, and/or BCL6, termed double-hit or triple-hit lymphomas, according to the 2016 WHO classification.23 Indeed, a small minority of patients (more with limited- than advanced-stage disease) are cured with a front-line nontransplant approach.24-28 A key retrospective analysis of 97 double-hit lymphoma patients who maintained first complete remission for at least 3 months with anti-CD20 and an anthracycline-based regimen had remarkable 3-year relapse-free and overall survival rates of 80% and 87%, respectively.25

It would be useful to carefully identify new clinical, molecular, and imaging markers that can better identify patients at high risk of early treatment failure in the rituximab era.— Syed Ali Abutalib, MD

Tweet this quote

Another retrospective series of 129 patients with double-hit lymphoma published by investigators at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center reported 3-year event-free and overall survival rates of 29% and 38%, respectively.26 A U.S. multicenter retrospective study of 311 patients with double-hit lymphoma reported 2-year progression-free and overall survival rates of 40% and 49%, respectively.27 In a prospective, multicenter, single-arm, phase II study of 53 patients with advanced disease, the 2-year event-free and overall survival rates were 71% and 76.7%, respectively.28

Unfortunately, patients with refractory or relapsed disease suffer extremely poor outcomes due to suboptimal responses to salvage chemotherapy. For example, in the MD Anderson series, the 3-year overall survival rate from the time of first progression was only 7%.25 Henceforth, in such patients, it would be reasonable to utilize a novel therapy (eg, CAR T-cell therapy) in a clinical trial, provided a reliable prognostic model or biomarker exists (ie, not FDG-PET2 using DS) that can signal early treatment failure. Such a risk-adopted approach would spare many patients from the unwanted toxicity of ineffective treatment and would maintain the possibility of a cure. Disappointingly, at the present time, such a model in double-hit and triple-hit lymphomas does not exist.

Justifying Change in Treatment

If the answer to the last three questions above is yes, then the decision to make an early change in therapy is justified, with an aim to increase the odds of a cure. However, if the answer is no, then why perform an interim FDG-PET2 scan, which is costly and will expose the patient to unnecessary radiation, inconvenience, and the additional toxicity of experimental therapy?

There is a paramount need to successfully identify patients with high-risk B-cell lymphoma who are likely to have a suboptimal response soon after the initiation of first-line therapy, to spare them from the unwanted adverse effects of ineffective treatment and to maintain the possibility of cure with second-line or early-salvage therapy. However, it is important to acknowledge that changing therapy based on the assumption that front-line therapy failed to be effective is neither a continuation of front-line therapy nor consolidation therapy. That said, most experts agree this likely represents early salvage therapy, which appears to be a superior strategy to treating patients with progressive disease relapse.

As the approach to personalized treatment continues to evolve, efforts are advancing to identify early treatment failure more accurately, thus opening the door to successful early intervention in patients with high-risk B-cell lymphoma.

Dr. Abutalib is Associate Director of the Hematology and BMT/Cellular Therapy Programs and Director of the Clinical Apheresis Program at the Cancer Treatment Centers of America, Zion, Illinois; Associate Professor at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science; and Founder and Co-Editor of Advances in Cell and Gene Therapy.

Disclaimer: This commentary represents the views of the author and may not necessarily reflect the views of ASCO or The ASCO Post.

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Abutalib has served on the advisory board for AstraZeneca.

REFERENCES

1. Neelapu, SS, Dickinson M, Ulrickson ML, et al: Interim analysis of ZUMA-12: A phase 2 study of axicabtagene ciloleucel as first-line therapy in patients with high-risk large B-cell lymphoma. 2020 ASH Annual Meeting & Exposition. Abstract 405. Presented December 6, 2020.

2. U.S. Food & Drug Administration: FDA approves axicabtagene ciloleucel for large B-cell lymphoma. Available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-axicabtagene-ciloleucel-large-b-cell-lymphoma. Accessed August 24, 2021.

3. U.S. Food & Drug Administration: FDA grants accelerated approval to axicabtagene ciloleucel for relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma. Available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-axicabtagene-ciloleucel-relapsed-or-refractory-follicular-lymphoma. Accessed August 24, 2021.

4. Moskowitz CH, Schöder H, Teruya-Feldstein J, et al: Risk-adapted dose-dense immunochemotherapy determined by interim FDG-PET

in advanced-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 28:1896-1903, 2010.

5. Tokola S, Kuitunen H, Turpeenniemi-Hujanen T, et al: Interim and end-of-treatment PET-CT suffers from high false-positive rates in DLBCL: Biopsy is needed prior to treatment decisions. Cancer Med 10:3035-3044, 2021.

6. Schöder H, Polley MC, Knopp MV, et al: Prognostic value of interim FDG-PET in diffuse large cell lymphoma: Results from the CALGB 50303 clinical trial. Blood 135:2224-2234, 2020.

7. Mamot C, Klingbiel D, Hitz F, et al: Final results of a prospective evaluation of the predictive value of interim positron emission tomography in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP-14 (SAKK 38/07). J Clin Oncol 33:2523-2529, 2015.

8. Adams HJ, Kwee TC: Prognostic value of interim FDG-PET in R-CHOP-treated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 106:55-63, 2016.

9. Sun N, Zhao J, Qiao W, et al: Predictive value of interim PET/CT in DLBCL treated with R-CHOP: Meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int 2015:648572, 2015.

10. Kim J, Lee JO, Paik JH, et al: Different predictive values of interim 18F-FDG PET/CT in germinal center like and non-germinal center like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Ann Nucl Med 31:1-11, 2017.

11. Dührsen U, Müller S, Hertenstein B, et al: Positron emission tomography-guided therapy of aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas (PETAL): A multicenter, randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 36:2024-2034, 2018.

12. Schmitz C, Hüttmann A, Müller SP, et al: Dynamic risk assessment based on positron emission tomography scanning in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Post-hoc analysis from the PETAL trial. Eur J Cancer 124:25-36, 2020.

13. Minamimoto R, Fayad L, Advani R, et al: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Prospective multicenter comparison of early interim FLT PET/CT versus FDG PET/CT with IHP, EORTC, Deauville, and PERCIST criteria for early therapeutic monitoring. Radiology 280:220-229, 2016.

14. Lunning MA, Armitage JO: Role of PET scan in lymphomas, in Abutalib SA, Markman M (eds): Cancer Consult: Expertise for Clinical Practice, pp 389-397. Hoboken, NJ; Wiley; 2015.

15. Cheson BD, Kostakoglu L: FDG-PET for early response assessment in lymphomas: Part 2: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, use of quantitative PET evaluation. Oncology (Williston Park) 31:71-76, 2017.

16. Barrington SF, Mikhaeel NG, Kostakoglu L, et al: Role of imaging in the staging and response assessment of lymphoma: Consensus of the International Conference on Malignant Lymphomas Imaging Working Group. J Clin Oncol 32:3048-3058, 2014.

17. Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al: Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: The Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol 32:3059-3068, 2014.

18. Burggraaff CN, de Jong A, Hoekstra OS, et al: Predictive value of interim positron emission tomography in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 46:65-79, 2019.

19. International Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project: A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med 329:987-994, 1993.

20. Ziepert M, Hasenclever D, Kuhnt E, et al: Standard International Prognostic Index remains a valid predictor of outcome for patients with aggressive CD20+ B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol 28:2373-2380, 2010.

21. Zhou Z, Sehn LH, Rademaker AW, et al: An enhanced International Prognostic Index (NCCN-IPI) for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated in the rituximab era. Blood 123:837-842, 2014.

22. Ruppert AS, Dixon JG, Salles G, et al: International prognostic indices in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A comparison of IPI, R-IPI, and NCCN-IPI. Blood 135:2041-2048, 2020.

23. Kluin PM, Deckert M, Ferry JA: Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the CNS, in Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al (eds): WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, pp 300-302. Lyon, France; International Agency for Research in Cancer; 2017.

24. Torka P, Kothari SK, Sundaram S, et al: Outcomes of patients with limited-stage aggressive large B-cell lymphoma with high-risk cytogenetics. Blood Adv 4:253-262, 2020.

25. Landsburg DJ, Falkiewicz MK, Maly J, et al: Outcomes of patients with double-hit lymphoma who achieve first complete remission. J Clin Oncol 35:2260-2267, 2017.

26. Oki Y, Noorani M, Lin P, et al: Double hit lymphoma: The MD Anderson Cancer Center clinical experience. Br J Haematol 166:891-901, 2014.

27. Petrich AM, Gandhi M, Jovanovic B, et al: Impact of induction regimen and stem cell transplantation on outcomes in double-hit lymphoma: A multicenter retrospective analysis. Blood 124:2354-2361, 2014.

28. Dunleavy K, Fanale MA, Abramson JS et al: Dose-adjusted EPOCH-R (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and rituximab) in untreated aggressive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with MYC rearrangement: a prospective, multicentre, single-arm phase 2 study. Lancet Haematol 5:e609-e617, 2018.