Francis S. Collins, MD, PhD

Dr. Collins is Director of the National Institutes of Health. Originally posted on March 19, 2018, to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Director’s Blog (https://directorsblog. nih.gov).

OVER THE PAST couple of weeks, we’ve lost two legendary scientists who made major contributions to our world: Sir John Sulston and Stephen Hawking. Although they worked in very different areas of science—biology and physics— both have left us with an enduring legacy through their brilliant work that unlocked fundamental mysteries of life and the universe.

I had the privilege of working closely with John as part of the international Human Genome Project, a historic endeavor that successfully produced the first reference sequence of the human genetic blueprint nearly 15 years ago, in April 2003.

Sir John Sultan. Photo by Jane Gitschier, PLoS.

As Founding Director of the Sanger Centre (now the Sanger Institute) in Cambridge, England, John oversaw the British contributions to this publicly funded effort. Throughout our many planning meetings and sometimes stormy weekly conference calls about progress of this intense and all-consuming enterprise, John stood out for his keen intellect and high ethical standards.

Most memorably, John was the most fierce and effective champion of making the vast troves of data generated by the Human Genome Project rapidly and publicly available to accelerate scientific discovery. In fact, he chronicled his experiences in helping to keep the Human Genome Project’s data free and open in his 2003 book, The Common Thread. John’s tireless efforts to promote data-sharing ultimately won over some of the more reluctant Human Genome Project partners and helped to establish a model of collaboration and data-sharing for many other large-scale biology projects. All of humankind is now benefiting from his vision, as researchers around the globe make use of these public data sets to advance human health.

The son of a former army chaplain and an English teacher, John graduated from Cambridge University in 1963 and did his postdoctoral research in the United States at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, California. He returned to Cambridge in the late 1960s and joined Sydney Brenner’s group in the Medical Research Council’s molecular biology lab. Researchers in the lab would occasionally repeat a remark attributed to Francis Crick, co-discoverer of DNA’s double-helix structure: “There is no point wasting good thoughts on bad data.” These words capture well John’s career as a scientist studying the model organism Caenorhabditis elegans, a transparent roundworm. His special gift was in developing strategies in C elegans to collect large amounts of good data that enabled good thoughts about its underlying biology. As John would say, by understanding the worm, it would be possible to understand life itself in all its mechanistic beauty.

Indeed, John was one of the first to understand that he could look intently through his microscope and follow along as cells divided in the worm, from egg to adult. It was exciting but demanding stuff, and John famously tracked the development of the young worm’s abdominal nerve tract over a weekend, becoming the first to follow in a living animal how genes instruct cells to move and sometimes die to create a needed biologic structure.

“From what I know about them, I’m quite sure that both Stephen and John considered it a privilege to spend their time on this planet in contemplation of its eternal mysteries. And for the fact they spent their time so extraordinarily well, we can all be forever grateful.”— Francis S. Collins, MD, PhD

Tweet this quote

Soon thereafter, John and his colleagues created a comprehensive cell lineage map for each of the 959 cells in C elegans. Their fundamental insights into the biology of a model organism have revolutionized our understanding of how genes control developmental processes and, when gone awry, can cause cancer or birth defects. For this amazing research and work that grew out of it, John was a co-recipient, with Brenner and colleague Robert Horvitz, of the 2002 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

It was a natural next step for John to co-lead the sequencing of the C elegans genome, which he did with Robert Waterston, producing the first complete DNA sequence of a multicellular organism in 1998. Moving on to the human genome, John and his Wellcome Trust–supported UK team ultimately contributed a full one-third of the human reference sequence. He is without a doubt one of the major heroes of this historic enterprise.

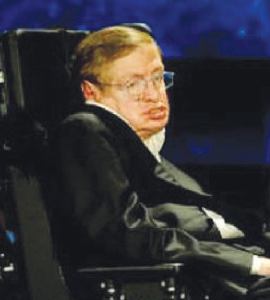

Stephen Hawking. Photo by Paul Alers, NASA.

I only met Stephen Hawking twice—once at the White House and once at the Pontifical Academy of Sciences at the Vatican. But he left a lasting impression on me, as he did on virtually all who knew of his work.

Like John Sulston, Stephen Hawking also studied at the University of Cambridge in the 1960s, earning a PhD in cosmology. During his first year at Cambridge, Stephen was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a progressively debilitating neurologic condition that he ably contended with throughout his life. He forged ahead with his studies, soon becoming a celebrity within the world of theoretical physics for his brilliant, dogma-dashing proofs about the quantum mechanics of black holes and the possibility that they could produce radiation.

In the 1980s, Stephen gained pop culture celebrity status with his bestseller A Brief History of Time, a lay overview of space, time, God, and the future. Like millions of other readers, I found that book to be amazing and illuminating. Other ways in which he helped to bring science to the masses included books that took readers on theoretical tours of the cosmos. A 2014 biographic film, The Theory of Everything, depicted the arc of Stephen’s phenomenal brilliance. “My goal is simple,” he once wrote. “It is a complete understanding of the universe, why it is as it is, and why it exists at all.”

Stephen never reached this complete understanding. Who could? But he certainly tried harder and contributed more than almost any other scientist of the current era. And he had a whole lot of fun along the way, sharing his keen observations on current events and his wry, self-deprecating sense of humor with many appreciative audiences, including viewers of The Simpsons, Star Trek: The Next Generation, and The Big Bang Theory.

From what I know about them, I’m quite sure that both Stephen and John considered it a privilege to spend their time on this planet in contemplation of its eternal mysteries. And for the fact they spent their time so extraordinarily well, we can all be forever grateful. ■

Disclaimer: This commentary represents the views of the author and may not necessarily reflect the views of ASCO or The ASCO Post.