Cancer-related pain does not exist in a vacuum. To effectively treat it, clinicians should understand the contributing factors. Proper assessment and management of cancer pain at the end of life can significantly alleviate patient suffering, according to Eduardo Bruera, MD, FAAHPM, Department Chair of Palliative Care and Rehabilitation Medicine in the Division of Cancer Medicine at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

“One of the challenges of pain in cancer patients close to the end of life is that it doesn’t come alone,” said Dr. Bruera at the 2015 Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer/International Society of Oral Oncology (MASCC/ISOO) International Symposium on Supportive Care in Cancer, held recently in Copenhagen.1 “It comes accompanied by fatigue, emotional distress, and the beginning of cognitive change, and it is in that context that we must assess and manage pain.”

He added, “Some patients have circumstances tougher than others, especially in countries where the likelihood of getting a painkiller is close to zero. The vast majority of patients who will die of cancer will never get a single dose of an opioid analgesic.”

Assessment of Pain

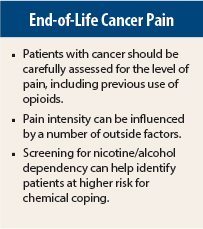

Dr. Bruera advised that clinicians first assess the pain mechanism (eg, cancer, infection, procedure), the intensity of pain and other symptoms, and previous use of opioids. “You might spend 25 minutes figuring out exactly what the pathophysiology is, and then you propose an opioid that made the patient very sick a few weeks ago, and your credibility is down the drain,” he said.

He recommended use of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System, which is completed by the patient and can measure multiple symptoms in less than 2 minutes.

When cancer patients are screened regularly, more symptoms are identified. “[With screening], you can discover eight symptoms in a visit vs two if [you rely on] the patient to volunteer the information,” he said. Screening also allows for comparison over time and quality assurance, which helps clinicians to understand how they are doing and what they can do better.

Pain Intensity: Only One Component

Pain intensity can be a useful numerical expression … but is “just a component of information for us,” said Dr. Bruera. Myriad factors can influence the number a patient uses to describe his or her pain (eg, the actual cancer, targeted therapy, divorce, emotional burden, loss of a job). “These are all part of the experience of suffering that affects patients, and that’s what they express.”

According to Dr. Bruera, the “ideal management of pain” includes a painkiller that is effective 24 hours a day; use of routine laxatives; and consideration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, adjuvant drugs, physical techniques, and anticancer therapy. He recommended the use of any strong opioid (morphine, hydromorphone, oxycodone, fentanyl, methadone, oxymorphone) and stated that they all have similar effects and toxicity.

Slow-release opioids are not better painkillers and have no reduced side effects, he told the audience. They are also five times more expensive than short-acting opioids. “For 35% of patients to whom I prescribe a slow-release opioid, the insurance company refuses to pay for it, and I need to change their painkiller,” he said. “Be aware that that can be a problem. However, they are more convenient, as the patient takes them less often.”

Dr. Bruera encouraged the use of adjuvant drugs, including corticosteroids, bisphosphonates, acetaminophen, and methylphenidate. “Certainly corticosteroids are fantastic, and methylphenidate can have a wonderful effect if the patient gets sleepy,” he said. “For neuropathy, we frequently end up having to make a litany of regimen changes (for example, trying opioids plus gabapentin, triycyclics, baclofen, lamotrigine, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors)—the question is which one works better for your patient.”

Practical Approach to Assessment

If a patient is not responding well to an opioid, Dr. Bruera recommends an enhanced assessment in which three amplifiers of expression should be identified: delirium, somatization (“total pain”), and addictive history.

Delirium can be caused by cancer, but it can also be caused by opiates. “Opiates can lead the patient to opiate-induced neurotoxicity, but it is important that we don’t universally blame the opioid, because there are other factors,” he said.

“A patient can get disinhibited because of the delirium, and they may perceive that their pain is worse,” he explained. “Patients with delirium will ‘hyperexpress.’”

If opioid-induced neurotoxicity occurs, begin opioid rotation and increase hydration, he advised. “Stop all of the offending drugs that you can, and it really doesn’t matter to which opioid you go,” said Dr. Bruera. “What matters is that you make the diagnosis that there’s opioid toxicity and you start the rotation, which is reasonably easy when methadone is not involved.”

Dramatic improvement in refractory pain symptoms has been demonstrated in most rotation studies. “One of the results when you rotate is that people feel better; their pain gets better,” he added.

Other Tools

The CAGE-AID questionnaire, which screens for alcohol and drug problems, can help to screen patients at high risk for using drugs, nicotine, or alcohol as a means of coping.

“Patients with nicotine or alcohol dependence might convey a higher risk for chemical coping with opiates,” said Dr. Bruera. “But absence of a history of chemical coping is no security at all,” he warned.

“The booze doesn’t matter. It’s a marker for the way your patient will cope chemically with an opioid,” he said. “Screening does not diagnose chemical coping, but the apparent behaviors are the ones that make the diagnosis.”

If a patient demonstrates chemical coping, educate the patient and family, create a supportive environment, prevent dose escalation, and rule out psychiatric disorders, he advised.

Finally, Dr. Bruera focused on the prevention of constipation, calling it a “huge issue.” “There is an underestimation of the suffering component of constipation in our cancer patients,” he said. “There’s no tolerance, and it’s completely underdiagnosed.” Appropriate diagnosis of constipation, education of the patient, and aggressive use of laxatives are crucial to alleviating this bothersome side effect.

“Ultimately, when a patient comes to me with increased pain, it might be cancer-related, but it could have nothing to do with the cancer,” said Dr. Bruera. “Close to the end of life, we address human suffering. And people have the right to call it whatever they want to call it.” ■

Disclosure: Dr. Bruera reported no potential conflicts of interest.

Reference

1. Bruera E: Cancer pain at the end of life: Rational and realistic management choices. 2015 MASCC/ISOO Annual Meeting. Parallel Session PS22. Presented June 27, 2015.