Dermatologic Events in Oncology is guest edited by Mario E. Lacouture, MD, an Associate Member in the Division of Dermatology, Department of Medicine, at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York. He is a board-certified dermatologist with a special interest in dermatologic conditions that result from cancer treatments and the author of many publications, including the recently published Skin Care Guide for People Living With Cancer. The series is intended to offer oncologists guidance in recognizing and treating the skin toxicities associated with anticancer agents.

The realization that targeted blockade of specific components of the MAP kinase pathway can be used to treat melanoma is considered by many to be one of the watershed moments in melanoma therapeutics. The resultant use of vemurafenib (Zelboraf) for the treatment of a subset of metastatic melanomas harboring the BRAF V600E mutation continues to be embraced with much enthusiasm by patients, physicians, and researchers.

However, this enthusiasm is somewhat mitigated by the observation that responses to BRAF inhibitor therapy are often not durable. Moreover, targeted therapy has the potential to paradoxically unmask the expression of other driver mutations, leading to a heightened risk for developing other cancers such as squamous cell carcinomas and second primary melanomas. Therefore, patients receiving vemurafenib therapy will likely benefit from periodic cutaneous surveillance examinations aimed at detecting and treating any second primary melanomas (as well as squamous cell carcinomas), while these neoplasms are thin and more easily curable.

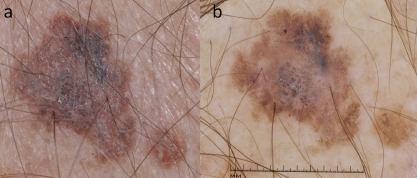

Research and clinical observations have revealed that melanomas and nevi that harbor the BRAF V600E mutation involute when the patient is given vemurafenib. While the new and darkening/enlarging nevi and the new melanomas developing in these individuals are BRAF wild-type, they do harbor other driver mutations such as in NRAS (Fig. 1) that may paradoxically activate the very same pathway targeted by vemurafenib, leading to unchecked proliferation. Given the paucity of targeted therapies for advanced BRAF wild-type melanomas, it behooves the clinician to diagnose these second primary malignancies as early as possible, while they are potentially amenable to cure via surgical excision.

A more formal evaluation to determine the degree of volatility of melanocytic lesions in patients on BRAF inhibitors is currently underway at multiple institutions. At Memorial Sloan-Kettering, we sequentially followed patients receiving vemurafenib with photographic images. Average photographic follow-up was 261 days (n = 21). The average number of combined new and changing melanocytic lesions per patient was 13.1, 16.4, 9.5, and 6.1 for the upper back, lower back, chest, and abdomen, respectively. Of all new and changing lesions, 38 were biopsied, revealing 31 benign melanocytic lesions and 7 melanomas (18% of lesions biopsied).

Management Recommendations

Patients on BRAF inhibitor therapy would benefit from periodic skin surveillance examinations. One proposal suggests skin examinations be performed at baseline, week 4, and every 12 weeks following initiation of therapy. Although not mandatory, obtaining photographs of the entire cutaneous surface can facilitate identifying new or changing lesions on subsequent examinations (Fig. 2). Additional evaluation of all new and changing lesions with dermoscopy can further increase the sensitivity and specificity for melanoma detection.

It is important to be aware that many nevi in these individuals will demonstrate clinical, dermoscopic, and histologic features of dysplastic nevi. The biologic potential of these “atypical” nevi remains to be elucidated. That said, many issues remain unresolved, including the advantages of intermittent dosing, the optimal frequency of surveillance skin examinations, even after therapy, and optimal frequency of examination after cessation of therapy.

Since patients with a previous melanoma are at increased risk for developing subsequent primary melanomas, many experts recommend lifelong surveillance examinations performed at least every 6 to 12 months. In addition, these patients should be instructed on the importance of protecting their skin from exposure to ultraviolet radiation and educated on the benefits of monthly skin self-examination looking for any new or changing lesions. ■

Disclosure: Dr. Marghoob and Ms. Yagerman reported no potential conflicts of interest.