“Physicians are afraid of morphine … Doctors [in Kenya] are so used to patients dying in pain … they think that this is how you must die. They are suspicious if you don’t die this way — [and feel] that you died prematurely.”

—Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. John Weru of Nairobi Hospice, Kenya, June 2007

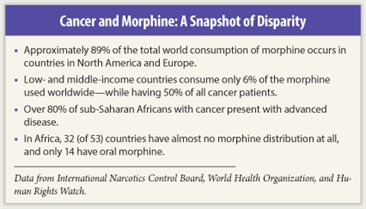

Despite initiatives by the world’s major health and policy organizations, 80% of persons worldwide suffering from severe pain still lack adequate access to morphine or other opioid analgesics—morphine is virtually nonexistent in over 150 countries. The global scope of unnecessary suffering is difficult to quantify, and—considering that morphine, which can alleviate more than 90% of cancer pain, costs pennies to produce—some pain experts consider depriving people in severe pain access to opioids tantamount to cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment by omission.

Epidemic in Developing Nations

In desperately poor areas of the globe, providing opioids for late-stage cancer pain is often a low clinical and political priority, competing with limited medical resources allocated for younger, healthier patients with a better chance of survival. Moreover, in the developing world, absence of government commitment, fractured infrastructure, and complex cultural and regulatory factors add extra barriers to pain-relief efforts on the ground.

In desperately poor areas of the globe, providing opioids for late-stage cancer pain is often a low clinical and political priority, competing with limited medical resources allocated for younger, healthier patients with a better chance of survival. Moreover, in the developing world, absence of government commitment, fractured infrastructure, and complex cultural and regulatory factors add extra barriers to pain-relief efforts on the ground.

“In areas such as sub-Saharan Africa, we’re dealing with ministries of health that are understaffed and underresourced, which leaves them little time to address an issue like access to morphine. At the same time, the ministry of health is the only governmental body with the authority and the skills to create and sustain change on a national level. In my experience, there’s no productive way to work around the government, so we need to be able to maximize those connections,” said Meg O’Brien, PhD, Director of the Global Access to Pain Relief Initiative (GAPRI), a joint program of the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) and the American Cancer Society.

“At GAPRI, one of our chief strategic interventions, and the focus of our programmatic work, is actually placing technical staff inside ministries of health, such as a Special Assistant to the Director,” said Dr. O’Brien. This type of intervention, explained Dr. O’Brien, was borne of the assumption that ministries of health in developing nations are not opposed to broad access to pain relief; they are simply overwhelmed with red tape and administrative issues.

“The health ministry simply doesn’t have anyone with capacity for navigating these quite complex bureaucratic issues. We give them someone who wakes up every day and focuses on a work plan that we’ve developed jointly with the ministry of health, following up on all the details, contracts, procurements, and such,” said Dr. O’Brien.

Dr. O’Brien stressed that many of the barriers to pain products stem from a bureaucratic void. “Our mission suffers because there is never anyone in the ministries of health whose job title includes pain relief. Since there’s no department, no one gets penalized at the end of the year for underperformance,” commented Dr. O’Brien.

“At UICC, we’ve found that a one-component intervention strategy doesn’t work. For instance, if we get the supply issue right, but we don’t work on demand; if we train clinicians, but we don’t work on procurement; if we raise awareness, but don’t provide training; it’s getting one right to the exclusion of the other, and things don’t move forward,” said Dr. O’Brien. She added, “For that level of coordination, we need to work closely with the ministries of health. It’s a time-consuming but necessary measure to bring relief to patients in pain.”

New Tools Needed

According to Willem Scholten, PharmD, MPA, Team Leader, Access to Controlled Medicines, World Health Organization (WHO), “Governments often create their own shortages by overregulating controlled substances on a national basis. The supply chains in these countries are delicate; any disruption can have severe consequences for pharmacies and patients.”

According to Willem Scholten, PharmD, MPA, Team Leader, Access to Controlled Medicines, World Health Organization (WHO), “Governments often create their own shortages by overregulating controlled substances on a national basis. The supply chains in these countries are delicate; any disruption can have severe consequences for pharmacies and patients.”

In 2007, under Dr. Scholten’s lead, the WHO developed The Access to Controlled Medicines Program to improve availability of pain medicines controlled under the drug conventions. One initiative was to improve the clinical tools needed to advance pain control efforts. “The WHO cancer pain guidelines, more than 15 years old, were not evidence-based. To convince policymakers around the world about pain, we needed new treatment guidelines, also covering all types of pain. We have finished the first set, the pharmacological treatment of persistent pain in children. The adult guidelines will follow,” said Dr. Scholten.

Another part of the program focused on policy guidelines: Ensuring Balance in National Policies on Controlled Substances. “The guidelines have a country checklist for methods to improve pain relief, using an even approach between prevention of drug misuse and the availability of opioid analgesics. The guidelines are an important tool for nations struggling with this challenge,” commented Dr. Scholten.

In addition to the guidelines, Dr. Scholten explained that WHO works with a variety of nongovernmental organizations and consortiums, conducting workshops in nations across the world, analyzing specific access barriers, whether cultural, economic, or political, and problem-solving ways to resolve inadequate pain control problems.

“At the World Health Assembly in 2005, a resolution was adopted to improve access to pain control medicine worldwide. Prior to that, the issue received little attention. It remains a huge challenge, but I am confident that as awareness continues to grow, we will see vast improvements in how we treat patients in pain,” said Dr. Scholten.

Rethinking the UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs

Opium is not only central to the relief of pain; it is also an internationally regulated substance. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the British expanded opium trade in Asia; by the end of the 1800s, growing consumption of the narcotic caused global concern, resulting in the 1909 International Opium Commission, setting the stage for the first international convention to regulate narcotics—the Hague Opium Convention of 1912. Flash-forward to 1961, when the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs led to highly restrictive international drug-control laws.

Opium is not only central to the relief of pain; it is also an internationally regulated substance. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the British expanded opium trade in Asia; by the end of the 1800s, growing consumption of the narcotic caused global concern, resulting in the 1909 International Opium Commission, setting the stage for the first international convention to regulate narcotics—the Hague Opium Convention of 1912. Flash-forward to 1961, when the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs led to highly restrictive international drug-control laws.

According to Allyn Taylor, JSD, of the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University Law Center and former legal adviser to WHO, ensuring medical availability of opioids constitutes a key but historically neglected aim of the international drug regime and a core legal obligation of the 183 countries that have ratified the UN Single Convention. “The twin aims of the Single Convention, as specified in its preamble and text, are to control the use and trafficking of substances with abuse potential while assuring availability of these drugs for scientific and medical purposes,” stressed Professor Taylor.

Implementing the aims of the Single Convention is a principal legal responsibility of the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) under the Convention. But according to Professor Taylor, driven largely by concern over illicit use of pain narcotics, the INCB has been historically lopsided in its mission, focusing primarily on problems of diversion and abuse, not ensuring access to pain medication. “This strict criminal justice approach to the Single Convention has hindered the capacity of many countries, particularly low-income nations, to ensure medical availability for their populations,” said Professor Taylor.

Onerous Burdens of Scheduling

Professor Taylor explained that issues involved in the scheduling of drugs are just one example of aspects of the Single Convention that impede the legitimate availability of pain medication. Schedule One, which morphine falls under, is subject to numerous legal restrictions on the international and local level, including onerous export-import records and authorizations. In short, bureaucratic and regulatory burdens of the scheduling process create unintended barriers to pain relief.

Professor Taylor explained that issues involved in the scheduling of drugs are just one example of aspects of the Single Convention that impede the legitimate availability of pain medication. Schedule One, which morphine falls under, is subject to numerous legal restrictions on the international and local level, including onerous export-import records and authorizations. In short, bureaucratic and regulatory burdens of the scheduling process create unintended barriers to pain relief.

“It’s important to note that many developing countries lack the resources needed to comply with the scheduling requirements and the attendant regulatory burden of the Single Convention. If a medicine is scheduled or rescheduled, poor states may simply ban a medicine with important public health purposes,” she stated.

Professor Taylor emphasized that although the Single Convention and the INCB play an important role in limiting illicit diversion of analgesics, there has long been a need for better balance between criminal justice and humanitarian needs. The risk of diversion of pain medication into illegal channels has not traditionally been one of the most critical challenges in international drug control.

However, over the past few years, nations as well as international organizations responsible for implementing the Single Convention, including the INCB and the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), have begun to to address the imbalance at the international level. “Both the INCB and the UNODC are evolving in their application of the Single Convention and are working more effectively with state parties, WHO, and other stakeholders to improve access to pain medication,” concluded Professor Taylor.

An Essential Human Right

According to Diederik Lohman, Senior Researcher, Health and Human Rights, Human Rights Watch, under international human rights law, governments must address a major public health crisis that affects millions of people every year; they must take steps to ensure that people have adequate access to pain treatment.

According to Diederik Lohman, Senior Researcher, Health and Human Rights, Human Rights Watch, under international human rights law, governments must address a major public health crisis that affects millions of people every year; they must take steps to ensure that people have adequate access to pain treatment.

Mr. Lohman stressed that in many low-income countries, the bulk of policy and monetary allocations are spent on curative treatments, even though the vast majority of patients in these regions present with late-stage or incurable disease. “For example, in India, approximately 70% of cancer patients are first diagnosed with advanced disease; however, the resources spent on palliative care are negligible, which means that about 70% of Indian cancer patients are basically forgotten,” said Mr. Lohman.

In pursuing steps to improve pain treatment, countries should draw on the expertise and assistance of the WHO Access to Controlled Medicines Programme and the International Narcotics Control Board. “To break out of this vicious cycle, individual governments and the international community must fulfill their obligations under international human rights law,” concluded Mr. Lohman. ■

Disclosure: Professor Taylor, Mr. Lohman, and Drs. O’Brien and Scholten reported no potential conflicts of interest.

SIDEBAR: Private/Public Health-care Divide Creates Disparity in Cancer Pain Treatment in South Africa

Approximately 15% of South Africa’s people have private health-care insurance and use private hospitals and clinics; another 10% also use private care paid out of pocket. However, the remaining 75% of South Africans use public health care, which is spread out over rural and urban areas.

Approximately 15% of South Africa’s people have private health-care insurance and use private hospitals and clinics; another 10% also use private care paid out of pocket. However, the remaining 75% of South Africans use public health care, which is spread out over rural and urban areas.