Treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) with tyrosine kinase inhibitors is “the golden child success story of targeted treatment,” Jerald P. Radich, MD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, Seattle, Washington, told attendees at the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) 10th Annual Congress on Hematologic Malignancies. “I don’t know of any other story showing the power of knowing the actual target of the agent and the agent affecting its biology. These things have made a huge impact on overall survival,” he added.

Game Changers

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors have had a huge impact on overall survival of patients with CML. The trick for clinicians, Dr. Radich suggested, is choosing the most appropriate agent for a given patient. “This question drives clinical care,” he added.

Eight years after treatment initiation with imatinib (Gleevec) in the landmark IRIS trial, approximately half of study subjects remained on the drug. Treatment has been associated with a complete cytogenetic response rate of 83%, transformation-free survival of 92%, and overall survival of 85%,1 he noted.

“No matter how you slice it, these patients have done fantastically well,” Dr. Radich observed. “This therapy has greatly decreased progression to accelerated phase and blast crisis.”

Use of the second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors, nilotinib (Tasigna) and dasatinib (Sprycel), as first-line treatment has produced higher rates of major molecular and complete cytogenetic responses. However, he indicated, overall survival is “curiously” no better.

The fact that the agents are essentially equivalent gives clinicians excellent options both for initial treatment and treatment after switching for patients with suboptimal responses.

Accuracy of Early Predictions

“At 12 months, you can pick out patients who will do great, and others for whom you need to consider Plan B,” he continued. In IRIS, event-free survival at 12 months was approximately 90% for patients with BCR-ABL/ABL ratio ≤ 0.1%, compared with approximately 50% for those > 10%.

However, predictions are accurate by 3 months, based on the achievement of a molecular response, or not, he added. In patients with BCR-ABL/ABL < 9.8%, overall survival has been reported at 93%, compared with 57% for those with levels > 9.8%.2 “After 3 months of initiating treatment, you can get a pretty good idea about who will do well and who won’t,” said Dr. Radich.

This time cutoff is more nuanced under certain conditions. “A poor response at 3 months is different for the person who takes the drug daily, vs the patient having toxicity and taking treatment breaks,” he noted. He cautioned that adherence to treatment, by patient report, is unreliable.

Although European guidelines suggest waiting 6 months before switching treatment, those of the NCCN, which Dr. Radich coauthored, accept the 3-month mark. There is not much data for switching at either time point, he acknowledged, “so why wait?”

“Trials show that progression to accelerated phase and blast crisis usually occurs soon after starting treatment, so if you wait from 3 months to 6 months, you will lose some patients to this,” he maintained.

Can Mutations Drive Second-Line Treatment?

Approximately half of patients who progress or become resistant to tyrosine kinase inhibitors have BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations, and the available tyrosine kinase inhibitors target them differently.

“In the clinic, you will find patients with mutations who should respond to a drug but don’t, and some who should not respond, but do,” Dr. Radich said. In general, however, mutation analysis can guide second-line treatment, and the NCCN recommends the following steps for particular mutation subsets:

- T3151: Consider ponatinib [Iclusig], omacetaxine [Synribo], stem cell transplant, or a clinical trial

- Y253H, E255K/V, or F359V/C/I: Consider dasatinib or a clinical trial

- F317L/V/I/C, T315A, or V299L: Consider nilotinib or a clinical trial

- E255K/V, F317L/V/I/C, F359V/C/I, T315A, or Y253H: Consider bosutinib [Bosulif] or a clinical trial

“But remember, in the second-line setting, you are not as likely to cure patients,” he pointed out. Complete cytogenetic responses are observed in only about 50% of patients in this setting.

“Most of us think resistance may be forever. It’s time to start HLA typing (finding a donor takes about 4 months) and having the conversation about transplant,” Dr. Radich advised. “If the patient responds well, then follow him [or her]. If not, move to transplant.”

When should the patient on second-line therapy be switched to a different drug? Several studies suggest that the optimal time is 3 to 4 months after starting the second-line agent, especially in patients lacking a complete cytogenetic response, he said.

Treatment Selection Based on Toxicity

For front-line therapy, the NCCN maintains there is no real difference in first- vs second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors in terms of efficacy or toxicity, although toxicity profiles do differ. Some toxicities are common to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor class, whereas others are unique to the drug, and this can help guide treatment selection among patients with underlying comorbidities.

Common side effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors are myelosuppression, increased transaminase levels, and change in electrolytes. Particular to imatinib are edema/fluid retention, myalgia, hypophosphatemia, and gastrointestinal side effects. The most concerning toxicity with dasatinib is pulmonary arterial hypertension; this tyrosine kinase inhibitor is also associated with pleural/pericardial effusions and bleeding risk.

As for other agents, nilotinib can increase the risk of cardiovascular events and is associated with increased pancreatic enzymes, indirect hyperbilirubinemia, hyperglycemia, and QT prolongation. With bosutinib, diarrhea, nausea, emesis, and rash are seen. Ponatinib is associated with thrombotic events and can also increase pancreatic enzymes, hypertension, and skin toxicity.

Discontinuing Treatment in Robust Responders

Some patients will continue to do well after treatment discontinuation, Dr. Radich noted. Studies have shown that among patients who are polymerase chain reaction–negative for several years and discontinue treatment, approximately 65% will relapse, usually within the first 3 months, but almost 40% will remain negative for BRC-ABL mutation for 2 to 3 years.3 Fortunately, patients who relapse and restart treatment usually return to a complete molecular remission.

“We don’t know the long-term consequences of this practice; therefore, these patients should be on a clinical trial,” he emphasized. With unopposed BCR-ABL activity, major clones may be downgraded, but minor clones may lie dormant and eventually create resistance, he said.

Dr. Radich suggested that clinicians consider treatment discontinuation in robust responders but continuing treatment when response is merely “good.” Patients with poor responses should be considered for transplant.

Key Messages

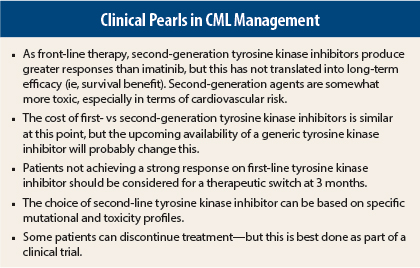

Dr. Radich summed up his talk regarding CML treatment with several key messages (see sidebar). He emphasized that although the NCCN Guidelines are “generic,” patients are clearly not generic, and their situations dictate individualized treatment. Second-generation agents, for example, may be preferred for the 30-year-old who wants to have children and does not want continuous treatment. These agents are more likely to produce a complete molecular response, which is required for treatment discontinuation. However, for the 70-year-old with some heart disease, disease control (and hopefully increased survival), without undue cardiac toxicity, may be the treatment goal, and for this patient, imatinib should be sufficient.

Finally, he added, “If the patient looks like chronic phase, but ‘smells like’ accelerated phase/blast crisis,” a second-generation agent is better. “Your clinical judgment trumps everything else.” ■

Disclosure: Dr. Radich reported no potential conflicts of interest.

References

1. Deininger M, O’Brien SG, Guilhot F, et al: International randomized study of interferon vs STI571 (IRIS) 8-year follow up: Sustained survival and low risk for progression or events in patients with newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase treated with imatinib. 2009 ASH Annual Meeting. Abstract 1126. Presented December 5, 2009.

2. Marin D, Ibrahim AR, Lucas C, et al: Assessment of BCR-ABL1 transcript levels at 3 months is the only requirement for predicting outcome for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. J Clin Oncol 30:232-238, 2012.

3. Rousselot P, Charbonnier A, Cony-Makhoul P, et al: Loss of major molecular response as a trigger for restarting tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy in patients with chronic-phase chronic myelogenous leukemia who have stopped imatinib after durable undetectable disease. J Clin Oncol 32:424-430, 2014.