In the fight against breast cancer, we must employ a combination of strategies…. Nevertheless, based on our experience in Israel, when an organized quality-controlled national screening program is implemented, tangible results can be obtained.— Eliezer Robinson, MD, Miri Ziv, MA, and Lital Keinan-Boker, MD, PhD

Tweet this quote

Recent years have seen the publication of a considerable amount of scientific literature questioning the effectiveness of mammography screening in decreasing breast cancer mortality.1-4 This article explores how the Israeli experience has demonstrated the efficacy of organized national mammography screening, initiated by the Israel Cancer Association at the end of the 1980s.

Breast cancer is the most common site of cancer in Israel: About 5,000 women are diagnosed with the disease each year. According to the National Cancer Registry, in 2012 there was an incidence of 95.5 per 100,000 Jewish women and 50.9 per 100,000 Arab women.5 Due to the high prevalence of breast cancer in Israel, the Israel Cancer Association, a nongovernmental agency working toward the reduction of cancer morbidity and mortality in Israel, has focused many of its activities on initiatives ranging from the promotion of research, prevention, and early detection to the enhancement of treatment modalities and rehabilitation means for cancer patients and survivors.

We focus here on activities relating to promoting and implementing early detection methods aimed at reducing breast cancer mortality in Israel.

Early Breast Cancer Screening Efforts

Since the 1960s, the Israel Cancer Association has established a network of breast examination clinics throughout Israel. About 80 such clinics were operating in Israel in the 1980s, staffed by surgeons and physicians specializing in physical breast exams. Such Israel Cancer Association–financed clinics operated in all hospitals, and clinics staffed by volunteer physicians operated adjacent to Israel Cancer Association branches across Israel. During 30 years of activity at these clinics, breast cancer mortality rates did not change, and epidemiologic evaluations did not indicate there was any real benefit to this effort.

In the early 1980s, the Israel Cancer Association implemented a training program for breast self-examinations across Israel. Along with dedicated surgeons, seminars were held for family physicians throughout the country, clarifying the importance of early detection and giving these clinicians the opportunity to update their knowledge and skills on how to perform manual breast exams. Workshops were also held for nurses so they could instruct and teach women in their community. They received training and watched demonstrations of the breast self-examination technique, which at the time was commonly thought to be a potentially effective means for early detection of breast cancer.

Since then, two large-scale controlled research studies were conducted, revealing there is no inherent benefit to the breast self-examination technique.6,7 Within the European Community, it is currently recommended not to encourage women to practice or perform breast self-examination,8 and a similar recommendation was made by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.9

Patient Education, Screening Mammography, and Quality Assurance

Alongside training activities, informational material was published and media campaigns were launched, conveying the message of the significance of early detection, which can potentially increase the chances of a cure. Thousands of workshops were held throughout Israel in collaboration with the country’s four Health Care Sick Funds. Through this activity, various myths were dispelled. Many women came to understand that a lump does not inevitably lead to cancer and that cancer is not necessarily a death sentence.

The intensive activity initiated by the Israel Cancer Association enhanced awareness of the importance of early detection. The national statistics, however, still had not changed, and no downstaging or mortality decline was observed.

Initial findings from controlled trials proving the effectiveness of mammography screening were reported at the end of the 1980s.10-12 In addition, a mammography screening pilot program launched by the American Cancer Society in the Los Angeles area was reported. Upon consultation, it was recommended that quality-control standards be implemented for the mammography equipment (according to American College of Radiology [ACR] principles) before women were referred for screening.

In 1989, based on this updated information and consultation, the Israel Cancer Association Executive Board decided to initiate a National Mammography Screening Program in Israel. When the Israel Cancer Association brought the request before the Ministry of Health, the administration’s initial reaction was that this subject was not on its list of priorities at the moment and that there were not enough radiologists and pathologists in Israel to carry out the program. The Israel Cancer Association Executive Board informed the Ministry of Health administration that its sole request at this point was to determine the condition of the 20 mammography units in operation at that time, mainly in hospital settings.

Apparently, the Israel Cancer Association had happened on a sore spot, as the Ministry of Health did not possess the equipment necessary to implement quality assurance on the mammography screening devices; thus, no information relating to these devices was available. Instead of “making headlines” regarding this revelation, the Israel Cancer Association opted for an agreement with the Ministry of Health, by which the Israel Cancer Association would finance the baseline survey regarding the existing mammography units and purchase the necessary equipment for their inspection. Concomitantly, the Ministry of Health undertook immediate action to implement the results of the baseline survey and to require the inspections according to ACR guidelines.

Challenges and Opportunities

A day after the survey results were obtained, the Director General of the Ministry of Health issued a directive to close five mammography units. Some of these units had extremely high radiation rates, which were certainly not suitable for diagnosing healthy women. These were outdated mammography devices situated in large hospitals.

The Israel Cancer Association had not yet begun to summon women for screening, so very few (primarily those with suspect palpable findings, for example) were examined by these devices. With financial assistance from the Israel Cancer Association, eight new mammography devices were purchased to replace those that were taken out of service.13

At this point, the Israel Cancer Association began to inform opinion leaders among health professionals of the importance of mammography screening and held a seminar for senior surgeons, oncologists, and family physicians, with the guidance of Edward A. Sickles, MD, Professor of Radiology and Senior Radiologist at the University of California, San Francisco. Immediately thereafter, several intensive workshops were held for radiologists, conducted by Dr. Sickles, along with Daniel B. Kopans, MD, PhD, Professor of Radiology and Senior Radiologist in the Breast Imaging Division at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical Center.

These workshops were aimed at training attendees on how to interpret a mammography screening image. Up until then, radiologists in Israel were solely trained in interpreting mammography images as a means of diagnosing findings that had been otherwise detected. Scores of radiologists from medical centers throughout Israel participated in these workshops. Meanwhile, skilled technicians from General Electric (manufacturer of the new devices purchased by the Israel Cancer Association) visited the mammography institutes and, via live demonstration, instructed attendees on how to correctly position the breast on the mammography unit to achieve optimal test results, as well as how to conduct daily and periodic quality-assurance tests on the equipment.

Fig. 1: ‘Invitation for Life’—one component of the media campaign targeting Israeli women, to clarify the importance of screening mammography.

Once this process was completed, the Israel Cancer Association launched a media campaign targeting the female population, which clarified the importance of the test (Fig. 1). The Ministry of Health responded positively to the Israel Cancer Association ‘s recommendation and instructed all national health-care plans to send a written invitation for a free mammography screening to all women over age 50 and up to age 75, every other year. (Women at higher risk of breast cancer are entitled to annual screening beginning at age 40, according to the attending physician’s recommendation.)

Eventually, a magnetic resonance imaging scan was also included in the health-care package for gene-mutation carriers. Several years later, the Ministry of Health included screening compliance as part of the quality indicators framework for monitoring the quality of health care provided by health-care funds.

The national program was evaluated according to European Union guidelines, and with this purpose in mind, the Israel Cancer Association enlisted the assistance of epidemiologist Gad Rennert, MD, PhD, who was officially appointed by the Ministry of Health as a Public Health Physician. The costs of the comprehensive evaluation program, which he implemented, have been covered by the Israel Cancer Association since 1992 and up to the end of 2013. (The Ministry of Health decided to transfer the responsibility for reporting the data to the Sick Funds. But to date, this move has not yet been completed.)

Gaps in Compliance and Care

Program statistics have revealed significant differences in compliance rates among various sectors of the population as well as between geographic and social peripheries. For example, in Omer, an affluent suburb of Beersheba, compliance rates were very high, as opposed to areas of Beersheba inhabited by low–socioeconomic status populations, where compliance rates were very low.

Thus, it became evident that despite the fact that the mammography screening test is provided free of charge, it is imperative that the service be made accessible to specific populations, particularly in Arab villages and in geographic and social peripheries, which are heavily populated by women who are less aware of the importance of the test. Consequently, the Israel Cancer Association Executive Board decided to purchase a designated mobile mammography screening unit.

Fig. 2: Uptake of mammography and its impact on screening compliance rate disparities in one Israeli district. CHS = Clalit Health Services. Source: Schwartzman H.14

One example of the impact of the mobile mammography unit was reported in one of the districts of the Clalit Health Services health-care fund, where eight clinics located in neighborhoods with low socioeconomic status demonstrated significantly lower compliance rates than the district average. By recruiting the mobile mammography unit and through a concerted team effort, this disparity was eliminated (Fig. 2).14

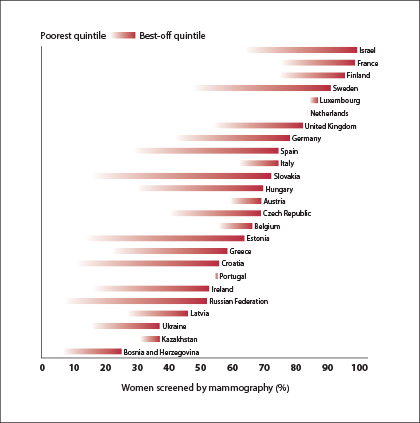

Fig. 3: Breast screening in selected member states of the World Health Organization European region, by wealth status. Source: World Health Organization.15

In fact, after initiation of the mobile mammography unit’s operation, a World Health Organization survey of the European Region revealed that Israel ranked first in compliance rates (Fig. 3).15 Moreover, the program continued to bridge gaps among diverse sectors of the population. The gap in compliance rates between Jewish and Arab women steadily narrowed,16 and in 2011, Professor Rennert reported the complete elimination of disparities observed in mammography screening compliance rates between Arab and Jewish women in Israel. The disparity was also reduced among ultra-Orthodox women, new immigrant women, and others.

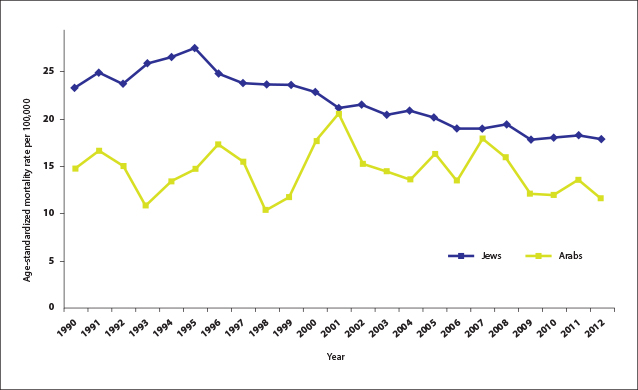

In the initial years of the program, Jewish women responded more quickly to the call to be screened. As a result, in 2010, the Central Bureau of Statistics and the National Cancer Registry reported a 25% decrease in breast cancer mortality rates among these women from 1998 to 2012 (from 23.6 per 100,000 in 1998 to 17.9 per 100,000 in 2012).17

An Organized Breast Cancer Screening Program

In Israel, the entire population is medically insured and entitled to all the medications and procedures included in the health-services basket. In other words, Jewish and Arab women who have been diagnosed with breast cancer are entitled to the same treatment, provided by the same physicians and multidisciplinary medical staff at the same hospitals.

Fig. 4: Breast cancer mortality in Israeli women, 1990–2012. Source: Israel National Cancer Registry.17

From 1990 to 2000, the mortality rates of Arab women had risen by 20%, alongside their increasing incidence rates, which doubled from 22.5 per 100,000 in 1990 to 50.9 per 100,000 in 2012 (Fig. 4).17 This rise in incidence and mortality rates is apparently due to a corresponding change in the lifestyle of Arab women: Compared with 1990, they now give birth later in life, to fewer children, breastfeed less, put on weight, and lead a more sedentary lifestyle. However, once they reached a screening compliance rate similar to that of Jewish women, a first-ever decrease in mortality was reported among Arab women, from a rate of 20.6 per 100,000 in 2001 to 11.5 per 100,000 in 2012.

In other words, in the past, despite the fact that Arab women received the same treatment, they had poorer survival because their disease was diagnosed at a later stage. Once their mammography screening compliance rates reached high levels, so they were diagnosed early and treated in a timely manner, a significant decline in their mortality rates was also observed.

Conclusions

To a great extent, experience in Israel has served as a “lab” for examining the effectiveness of breast cancer–detection methods. The Israel Cancer Association’s efforts to promote a national chain of physical breast examination clinics and to train women to perform breast self-exams have indeed enhanced breast cancer awareness, and have dissipated myths and misconceptions, but they have not helped to improve outcomes. Conversely, the Israel Cancer Association–initiated National Mammography Screening Program has helped achieve a reduction in breast cancer mortality rates in Israel.

The trends in the Arab female population in Israel attest to the fact that once their screening compliance rates improved, and they were diagnosed and treated at an early stage, they also attained significantly enhanced survival rates. Most importantly, a significant reduction in breast cancer mortality was achieved.

In the fight against breast cancer, we must employ a combination of strategies, including research promotion (to find more effective prevention and early detection methods and treatment modalities), implementation of professional standards for comprehensive breast units, and improved access to updated treatment modalities. Nevertheless, based on our experience in Israel, when an organized quality-controlled national screening program is implemented, tangible results can be obtained. ν

Disclosure: Dr. Robinson, Ms. Ziv, and Dr. Keinan-Boker reported no potential conflicts of interest.

References

1. Raftery J, Chorozoglou M: BMJ 343:d7627, 2011.

2. Marmot MG, Altman DG, Cameron DA, et al: Br J Cancer 108:2205-2240, 2013.

3. Independent UK Panel on Breast Cancer Screening: Lancet 380:1778-1786, 2012.

4. Autier P, Esserman LJ, Flowers CI, et al: Nat Rev Clin Oncol 9:599-605, 2012.

5. Lifshitz I, Fishler Y, Dichtier R, et al: Israel National Cancer Registry and Israel Center for Disease Control statistics, Ministry of Health, 2015.

6. Semiglazov VF, Moiseenko VM, Manikhas AG, et al: Vopr Onkol 45:265-271, 1999.

7. Thomas DB, Gao DL, Self SG, et al: Natl Cancer Inst 89:339-340, 1997.

8. McCready T, Littlewood D, Jenkinson J: J Clin Nurs 14:570-578, 2005.

10. Tabár L, Gad A, Holmberg L, et al: Diagn Imaging Clin Med 54:158-164, 1985.

11. Shapiro S: World J Surg 13:9-18, 1989.

12. Shapiro S: J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr (22):27-30, 1997.

13. Israel State Comptroller and Ombudsman: 46th Annual Report for 1995 [in Hebrew]. Jerusalem, 1996.

14. Schwartzman H: Presented at the joint conference of the Israeli Association of Public Health Physicians, the Israeli Family Physicians and the Israeli Oncologist Association, Ramat Gan, Israel, November 2008.

15. WHO World Health Statistics 2008. Part 1: Ten highlights in health statistics. Available at www. int/who/publications/world_health_statistics/EN_WHS08_Full.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2016.

16. Rennert G: The Annual Report of the National Israeli Breast Cancer Screening Program [in Hebrew]. Israel Ministry of Health and Israel Cancer Association. Jerusalem, 2010. Available at www.cancer.org.il/dover_news/new.aspx?NewId=1668. Accessed July 6, 2016.

17. Liphshitz I, Fishler Y, Dichtiar R, et al: [in Hebrew] Israel National Cancer Registry, the Israel Center for Disease Control, Ministry of Health, 2015. Available at www.health.gov.il/PublicationsFiles/breast_cancer_oct2015.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2016.