Keith L. Black, MD

For this installment of the Living a Full Life series, guest editor Jame Abraham, MD, spoke with noted neurosurgeon Keith L. Black, MD, Chair of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center’s Department of Neurosurgery and Director of the Maxine Dunitz Neurosurgical Institute. During his career, Dr. Black has performed more than 7,000 brain tumor operations, and his visionary discoveries, such as identifying the compound that enables chemotherapy to penetrate the blood-brain barrier, have revolutionized the treatment of brain cancer.

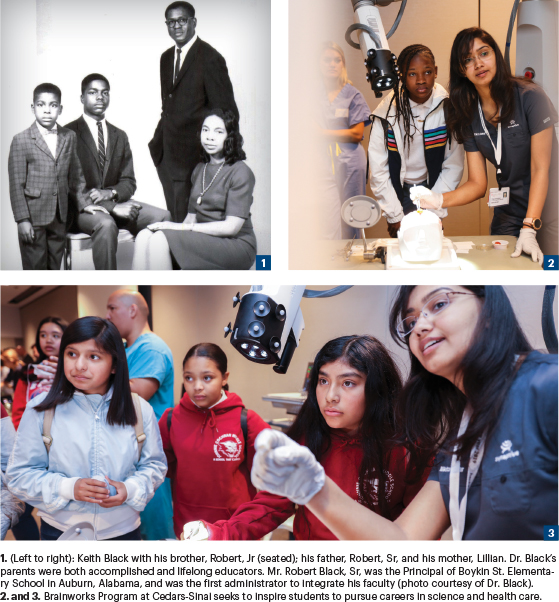

Pioneering neurosurgeon Keith L. Black, MD, was born in 1957, in Tuskegee, Alabama, a time and place that were at the tumultuous epicenter of the national Civil Rights Movement. “My parents actually lived in Auburn, but since the hospitals there were segregated, my mother had to travel to Tuskegee to give birth to me,” Dr. Black related. “Both my parents were educators; my father was the principal of the all-black Boykin Street Elementary School, where my mother taught first grade. I have an older brother, and we lived in Auburn until I was 10. It was an interesting time.”

KEITH L. BLACK, MD

On remembering his father: “He taught his students the philosophy of civil disobedience that led protests over segregation in front of the mayor’s office.”

On the current climate of civil unrest: “There’s a sense of disappointment that over the past 50 years, we are still dealing with the same issues that were around in the 1950s in terms of inequity and justice.”

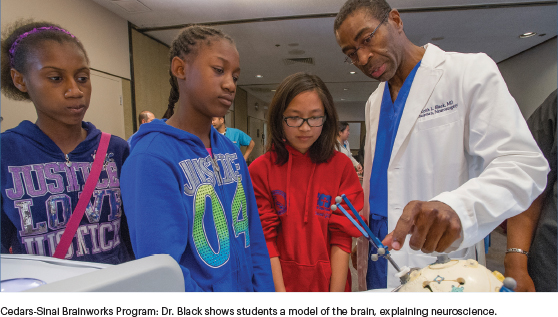

On the Brainworks mentorship program: “We bring students in from the 7th and 8th grades and give them the tools and guidance to learn the rudiments of neuroscience.”

Dr. Black continued: “I grew up in a middle-class Black community comprised largely of teachers and lawyers and others in the professional class, which served me very well in my developmental years. My father, who did his graduate training at the University of Pennsylvania, returned to Auburn to promote civil rights and integrate his school, not with White students, which wasn’t permitted, but to integrate the staff. He actually brought in White teachers and conducted what I would describe as behind-the-scenes activism. He taught his students the philosophy of civil disobedience that led protests over segregation in front of the mayor’s office,” said Dr. Black.

At the age of 10, Dr. Black’s family opted to leave the segregated South and relocate to Cleveland, Ohio, which offered better educational opportunities for Dr. Black. “Shortly after we settled in Cleveland, my interest in science and medicine began to bloom. My parents had sent my brother, who is 8 years older than me, up to a private school in New Hampshire, as they didn’t want him to be forced into a segregated school. Because of financial circumstances, we couldn’t afford to buy a house in Shaker Heights, but we rented so I could go to the district’s wonderful public-school system, which offered a terrific educational opportunity,” said Dr. Black.

GUEST EDITOR

Jame Abraham, MD, FACP

A Passion for Science

Dr. Black’s nascent interest in science developed into a passion. “When I was in the 8th grade, I would ride my bicycle out to Case Western Reserve University and sit in the medical library, flipping through the pages of Index Medicus, looking for potential research projects. Actually, a lot of the projects were focused on cancer. I even developed a relationship with an oncologist who directed me to an apprenticeship program for high school students from minority backgrounds, where I began to learn basic laboratory skills,” said Dr. Black.

After the apprenticeship program, Dr. Black’s enthusiasm for research and medicine accelerated. While still in high school, he was offered a part-time job at Cleveland’s St. Luke’s Hospital, as an assistant to Frederick Cross, co-inventor of the Cross-Jones artificial heart valve. “Dr. Cross was kind enough to introduce me to his PhD researcher, Dr. Jones, and I volunteered in the lab, basically cleaning test tubes and other menial chores. Eventually, I worked my way up to an assistant, as they performed transplant surgeries and heart valve replacements on laboratory dogs. During this work, I felt the force of the heart valve’s pressure might damage red blood cells. The lab had just purchased a scanning electron microscope, and I asked Dr. Jones if I could do an experiment looking at red blood cells from the dogs who underwent heart valve replacements. At first, Dr. Jones was reluctant to let a high school student experiment with the new and costly microscope, but my persistence paid off. I was able to conduct my experiments of red blood cell damage,” said Dr. Black.

Dr. Jones was so impressed with the young prodigy that he let Dr. Black attend some of Dr. Cross’ heart surgeries and draw blood from patients on the heart-lung bypass machine, so he could perfect the technique of preparing the sample slides. “We had to incubate the blood overnight. One thing I noticed the next day in the incubated blood of patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass was the cell morphology had transformed. I was able to refocus my research on that observation,” shared Dr. Black.

Early Science Experiments

Dr. Abraham asked Dr. Black whether there were any seminal events that spurred such intense interest in science. Dr. Black commented: “I was always interested in what made live things work. I’d look at my older brother’s science books and become fascinated with anatomy, spending hours identifying various body parts and organ systems. My father was also important in my maturation from interest to actual doing. One day, my father came home from the local slaughterhouse with a cow heart he’d purchased for me to dissect.”

Dr. Black’s observations formed the groundwork for his first scientific paper, published at age 17. The paper also won him the prestigious National Westinghouse Science Talent Search competition, which solidified his decision to pursue a career in science and medicine. Following his graduation from Shaker Heights High School, Dr. Black was accepted to the University of Michigan Medical School’s accelerated program, allowing him to complete an undergraduate degree and medical school in 6 years. He received his medical degree at the age of 23.

A Lifelong Mentor

Dr. Abraham asked what initiated Dr. Black’s research efforts at the University of Michigan. “During my first year of medical school,” Dr. Black noted, “I realized I could master the accelerated course work, so I turned back to research, which was my original passion. I made an appointment to meet with the head of one of the school’s research programs. Once there, I was connected with a cardiologist Dr. Otello Randall, who became a lifelong mentor and friend. He was one of the only Black cardiologists at the university at that time. Working with him not only formed my scientific foundation, but in our discussions, he gave me pearls of wisdom that have served me well throughout my career to this very day,” said Dr. Black.

A Brain Surgeon Arrives

After taking his first course in neuroanatomy, Dr. Black realized he’d found his true passion: the human brain. Dr. Black spent the next 3 years at the University of Michigan Medical School researching stroke prevention as he continued his medical training. “My research on stroke transitioned to investigating mechanisms of blood-brain barrier regulation, and ultimately that work allowed me to begin research efforts on increasing the ability of chemotherapeutics to cross the blood-brain barrier for treatment of brain tumors. Along with my clinical rotations during residency, I was able to conduct my research projects,” said Dr. Black.

After Dr. Black completed his internship and neurosurgical residency at the University of Michigan in 1978, he accepted a position as Assistant Professor of Neurosurgery at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). During this career move, Dr. Black needed to decide whether to continue his work as a neurovascular surgeon or as a brain tumor surgeon. “I decided to focus on brain tumors, as I saw an opportunity to further my research on delivering therapeutics across the blood-brain barrier to treat malignancies of the brain,” said Dr. Black.

Pioneering Surgical Techniques

Along with his research on the blood-brain barrier, Dr. Black spent the next decade tackling surgical issues in brain surgery, perfecting brain tissue–sparing techniques, and continuing his research to discover new ways of delivering novel chemotherapeutics to brain tumors. His research bore fruit, and in 1994, Dr. Black patented a novel therapy, using RMP-7, a synthetic version of bradykinin that allows agents to attack brain tumors without damaging healthy tissue. After a decade at UCLA, Dr. Black accepted a leadership position at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in the Center’s Maxine Dunitz Neurological Institute. By then, his reputation as a leader in neurologic malignancies had drawn national attention.

At Cedars-Sinai, Dr. Black continued his pioneering work, developing novel strategies in immunotherapy as well as new surgical approaches to resect tumors while sparing vital brain tissue. In 2007, Dr. Black opened a new brain tumor research center at Cedars-Sinai, named for the renowned late defense attorney, Johnnie L. Cochran, who was a patient of Dr. Black and a close friend. Dr. Black’s autobiography, Brain Surgeon, was published in 2009.

Unrest and Unity: Still Work Ahead

As the son of a civil rights advocate who grew up under the South’s segregation policies, Dr. Black reflected on today’s civil unrest. “I look at what’s happening today with multiple emotions. To begin, there’s a sense of disappointment that over the past 50 years; we are still dealing with the same issues that were around in the 1950s in terms of inequity and justice. When we examine not only police brutality, but also disparities in education and health care among Black individuals, it becomes obvious we have a long way to go in the effort to achieve justice and equality in a society that is far less color-

blind than it should be.”

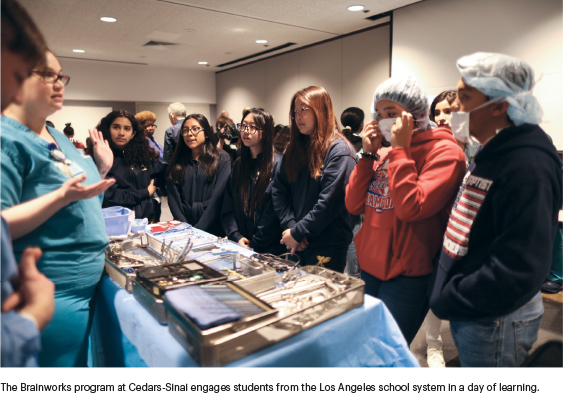

For the past 20 years, Dr. Black has focused on mentorship to help bring bright young talent from diverse backgrounds into medicine. “We started a program at Cedars called Brainworks, where we bring students in from the 7th and 8th grades and give them the tools and guidance to learn the rudiments of neuroscience. We also have other programs at Cedars for students from challenged backgrounds, including the Pauletta and Denzel Gifted Scholars program and the Ray Charles Scholars program, and I am working with the University of Michigan on a program called Pathways. So, we can do numerous things on a grassroots level to help the underserved have a better chance for success, despite the social biases they may confront on a daily basis,” said Dr. Black.

“Despite the challenges, I’m encouraged to see so many White people standing shoulder to shoulder with Black people during the protests. This needs to be a process we commit to and remain focused on, for however long it takes, before substantive change has been made to the system,” said Dr. Black.

Words for ASCO Colleagues

Toward the end of Dr. Abraham’s interview, Dr. Black addressed his ASCO colleagues. “As a clinical scientist I’m hopeful in the progress we’ve made over the past decades in some of the brain cancers we treat, particularly with some of the emerging immune strategies. That said, the progress has not been as rapid as we’d like to see. I would encourage my fellow ASCO members to think outside of the box, considering strategies we’ve potentially overlooked in our search for solutions in this challenging setting.”

Dr. Black continued: “To deliver better care, it’s important for members of ASCO to understand we all carry biases, both conscious and unconscious. It is vital to grapple with unconscious bias to deliver high-quality equitable care, regardless of a patient’s color or socioeconomic background. The Society has taken steps in that direction, and although there’s a lot of work ahead, I remain optimistic about a fairer and equal nation.”

How does a super busy brain surgeon decompress? “I have a great wife, who is also a physician, and we have two children, so family life is the best way to get away from the stress of work. I also enjoy outdoor sports and traveling. I love the ocean, and when I get the chance, I venture out to sail and scuba dive; it truly brings you to another world.”