The global toll of breast cancer on women is staggering. In 2018, nearly two million new breast cancer cases were diagnosed, an increase of more than 20% since 2008,1 and mortality rates have increased by 14%, bringing the annual number of deaths worldwide from the cancer to more than 611,625.2 Although breast cancer is potentially curable when found early, the mortality-to-incidence ratios for the disease are significantly worse for women living in low- and middle-income countries, where most patients present with late-stage disease, compared with women in high-income countries. For example, some of the mortality-to-incidence ratios reported in Middle, Eastern, and West Africa are as high as 0.55, compared with 0.16 in North America.3

“In high-income countries, women diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer generally live after their diagnosis, but unfortunately, that is not the case in low-resource countries, where the cancer is often detected at a late stage when cure is not possible,” said Sabrina Zucchello, Grants Manager at the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC). “In the settings of low- and middle-income countries, according to the ABC Global Alliance, it is estimated that between 50% and 60% of breast cancers are diagnosed at stage III or IV. In some countries, the percentage can be as high as 80%, compared with approximately 10% in high-income countries.”

The barriers to receiving life-saving breast cancer care in low-resource countries are many and include limited to no access to early detection programs and a shortage of cancer specialists—in Ethiopia, for example, there are just 4 oncologists for its 100 million citizens4—diagnostic tools, radiotherapy machines, and chemotherapies. Poverty, civil wars, and mass displacement compound the problem, as do fear, stigma, and lack of awareness surrounding the prevention and early detection of breast cancer.

“There is a lot of fear about cancer, and women risk being rejected by their family in many countries, so it is not easy to face a cancer diagnosis,” continued Ms. Zucchello. “As a result, many women use different mechanisms to cope, and ignoring the early signs of the disease is one. Many women are just not aware of the early signs of breast cancer. Even when the cancer is found at an early stage, crucial time can be lost between when the patient receives the diagnosis and is referred for the right treatment, which can take months.”

Making a Difference

To reduce the global burden of metastatic breast cancer and improve patient outcomes, in 2015, UICC, together with Pfizer Oncology, launched the Seeding Progress and Resources for the Cancer Community (SPARC) Metastatic Breast Cancer (MBC) Challenge (www.uicc.org/what-we-do/capacity-building/addressing-metastatic-breast-cancer-mbc). This challenge awards $25,000 grants to seed projects that address the specific needs of women living with metastatic breast cancer, raise public awareness on prevention and early detection strategies, influence national health-care policies, and strengthen local health-care systems.

Since the inauguration of the initiative, the SPARC MBC Challenge has provided $1,580,000 in grants to more than 50 awardees from 35 countries. These grants have translated to the

development of patient support groups and advocacy, patient education programs, and patient navigation models. Over the past 5 years, these projects have directly benefited more than 14,000 patients in low-resource countries; reached more than 140,000 people through advocacy campaigns and educational materials; and trained more than 2,300 medical professionals in palliative care, patient advocacy, and patient navigation.

Featured here are two of the 2017 awardees: Kara Magsanoc-Alikpala and Ebele Mbanugo, EdD. Both exemplify how one person can have a positive impact on the lives of thousands of women diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. “These two women are inspiring leaders, and both have a personal experience with breast cancer,” shared Ms. Zucchello. “Through that experience, Kara and Ebele were able to measure the immense need of patients with metastatic breast cancer in their communities and help fill the gaps in medical care. Through their efforts, they have turned their personal pain and loss into hope for others.”

Kara Magsanoc-Alikpala Founder, ICanServe Foundation, Manila, Philippines

Ms. Magsanoc-Alikpala began her work in patient advocacy after a mass she had detected in her left breast went undiagnosed for 2 years and resulted in a more advanced stage of lobular carcinoma. Told by her physician that she was too young to have breast cancer, even after a mammogram found the lump to be “suspiciously malignant,” it wasn’t until her father insisted she have the mass biopsied that the diagnosis was finally made. This lesson has stayed with her ever since, and she uses it to prevent other women from making the same mistake.

“I’m a journalist and in the business of gathering information and I didn’t know about breast cancer in young women. I felt shame for not knowing breast cancer can affect younger women and for not trusting my instincts,” said Ms. Magsanoc-Alikpala. “The cancer could have been diagnosed years before at an earlier stage, when I could have avoided undergoing chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation treatments, which nearly cost me the chance to have a child. I became a patient advocate to give back for having my wish come true to have a child.”

Providing Access to Cancer Care

In 1999, 2 years after her diagnosis, Ms. Magsanoc-Alikpala launched the ICanServe Foundation (www.icanservefoundation.org). It provides educational programs to raise awareness of the prevention and early detection of breast cancer in the Philippines, which had nearly 25,000 new cases in 2018, among the highest in Asia.5 With no national breast cancer screening program in the Philippines and a poverty rate of nearly 17%,6 timely checkups for the prevention and early detection of cancer are out of reach for many Filipino women.

“The unmet medical need for poor women is financial,” explained Ms. Magsanoc-Alikpala. “Our National Health Insurance Program covers treatment only for women with early-stage breast cancer, but women who cannot afford to see a doctor for an annual physical exam rarely discover their breast cancer at an early stage. Palliative care and pain management services are available only for those who can afford such care. There are few programs to help support the medical needs of poor people, who have to pay for care out-of-pocket.”

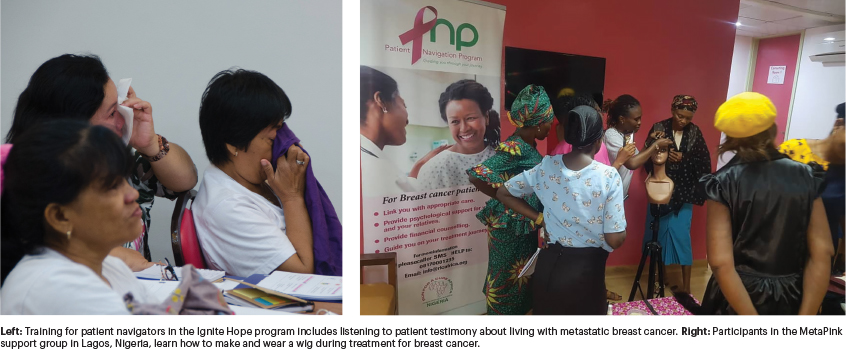

To improve care for women with breast cancer, especially those with metastatic disease, in 2016, Ms. Magsanoc-Alikpala applied for a $25,000 SPARC grant for her Ignite Hope: Patient Navigation Program. The goals of the initiative are to train patient navigators in four cities in metro Manila (Marikina, Malabon, Muntinlupa, and Taguig); enhance existing early breast cancer detection programs in these cities and establish programs for patients with late-stage disease to help them access free or low-cost services and medicines; and educate patients and their family members about the disease.

“There are still so many myths surrounding breast cancer in my country,” Ms. Magsanoc-Alikpala noted. “For example, some husbands think breast cancer is contagious and send their wives away. Many people believe having breast cancer is a death sentence, even when it is discovered at an early stage, so patient navigators can provide a lot of information.” Although the complete results of the Ignite Hope program (https://www.uicc.org/case-studies/strengthening-care-metastatic-breast-cancer-philippines-through-patient-navigation-and) are still being evaluated, since the program launched in 2018, 56 patient navigators have been trained throughout the four cities.

Bringing Universal Health Care to the Philippines

In addition to instituting a patient navigation program in the Philippines, in February 2019, Ms. Magsanoc-Alikpala realized another long-held dream: passage of the National Integrated Cancer Control Act. This legislation aims to provide timely access to cancer treatment for all patients throughout the Philippines and improve survival rates. Through her ICanServe Foundation, Ms. Magsanoc-Alikpala cofounded Cancer Coalition Philippines, which lobbied for passage of the law.

“The National Integrated Cancer Control Act can now become the health-care model for other countries to emulate,” she noted. “We are proud we were able to help get this law passed. At least there is hope in our country now that women with breast cancer and all adults and children diagnosed with cancer will have access to more affordable treatment and that the burdens on patients, including financial and stigmatization, will be eliminated.”

Ebele Mbanugo, EdD Executive Director, Run for a Cure Africa Breast Cancer Foundation, Lagos, Nigeria

For Dr. Mbanugo, 2007 was expected to be a very good year. She was pregnant with her first child and looking forward to her older sister’s wedding. However, the news that her mother, Ifeoma Nwankwo, had found a lump in her breast and that two of her aunts had just been diagnosed with cancer (one with breast and the other with colorectal) turned her joy into paralyzing fear and left her searching for information.

“When my mother was diagnosed with breast cancer, I knew nothing about the disease,” related Dr. Mbanugo. “It was not on our radar, and we were scrambling for information on her prognosis. After her mother underwent 6 weeks of chemotherapy followed by radiation therapy, the cancer went into remission. (However, she later died of cancer recurrence in 2016.) Once again, Dr. Mbanugo’s joy was tempered by sadness at the death of her aunt a few months after receiving a diagnosis of colorectal cancer. However, the tragedy also catapulted her to take action against a disease that had taken hold of her family.

In 2009, she organized a run in her hometown of Lagos, Nigeria, to raise awareness of breast cancer and funds to purchase mammography machines for local hospitals. The community event eventually led to the creation of the Run for a Cure Africa Breast Cancer Foundation (www.rfcafrica.org).

Paying It Forward

“When my aunt was diagnosed with colorectal cancer, her son was told to take her home so she could spend the Christmas holiday with her family,” Dr. Mbanugo continued. “That really hit me hard because it would have devastated my siblings and me if our mother’s doctor had said that to us. Launching the breast cancer run was a way for me to pay it forward and help women receive free breast cancer screening and give them a better chance at survival.”

Although the incidence of breast cancer is declining in some parts of the world, it is increasing in Nigeria, where the number of new cases in 2018 reached 26,310.7 Nigeria also has the highest mortality rate from the cancer of any other country in Africa, estimated at 10,000 each year,8 and 75% of patients are diagnosed at stage III or IV.9

Contributing Factors to Late-Stage Diagnosis

Many assorted factors contribute to the high incidence of late diagnoses and deaths in Nigeria. They include a lack of awareness of the symptoms of breast cancer, little to no access to screening facilities, a dearth of oncology specialists—fewer than 70—to provide care for a country with an estimated population of 186 million,10 poverty, confusion over how to navigate the Nigerian health-care system, as well as the myths and stigma surrounding the disease.

Bringing Empowerment to Breast Cancer Survivors

With the $25,000 grant Dr. Mbanugo received from the SPARC MBC Challenge, she launched the MetaPink program (https://www.uicc.org/case-studies/improving-quality-life-

metastatic-breast-cancer-patients-nigeria) to provide information and resources to patients with late-stage breast cancer to improve their quality of life and overall prognosis. Through this program, patients have access to monthly support group meetings, which include makeup tutorials, information about their treatment plan and its potential side effects, and question-and-answer sessions with medical professionals. The program has been a revelation to many participants.

“When we started the support group meetings, more than 26 women came. I asked the women what their diagnosis was, and not one of them could articulate what their diagnosis meant,” commented Dr. Mbanugo. “They were told they had breast cancer, and that’s why they came to the meeting. In our culture, we don’t question what a doctor tells us to do; we just do it.”

Dr. Mbanugo continued: “Through our support group meetings, we are able to build patients’ self-efficacy. We give them questions to ask their doctor, for example, what type of cancer do I have? What does HER2-positive breast cancer mean? What is my prognosis? One of our biggest accomplishments with the program is helping women to become educated about their disease. Women have to be able to see they have some power and control over their cancer.”

DISCLOSURE: Ms. Zucchello, Ms. Magsanoc-Alikpala, and Dr. Mbanugo reported no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Breast Cancer Research Foundation: Breast cancer statistics and resources. Available at www.bcrf.org/breast-cancer-statistics-and-resources. Accessed June 4, 2020.

2. Roser M, Ritchie H: Cancer. July 2015; updated November 2019. Available at https://ourworldindata.org/cancer. Accessed June 4, 2020.

3. Martei YM, Pace LE, Brock JE, et al: Breast cancer in low- and middle-income countries: Why we need pathology capability to solve this challenge. Clin Lab Med 38:161-173, 2018.

4. Mortimer JE: ASCO International course helps Ethiopia realize its goal of improving cancer care. June 27, 2016. Available at https://connection.asco.org/magazine/asco-international/asco-international-course-helps-ethiopia-realize-its-goal-improving. Accessed June 4, 2020.

5. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC): The Global Cancer Observatory, IARC, World Health Organization: Philippines. Available at https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/608-philippines-fact-sheets.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2020.

6. Republic of the Philippines National Economic and Development Authority: Preliminary report of the 2018 full-year official poverty statistics of the Philippines. December 6, 2019. Available at www.neda.gov.ph/as-delivered-statement-on-the-official-poverty-statistics-of-the-philippines-for-the-full-year-2018/. Accessed June 4, 2020.

7. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC): The Global Cancer Observatory, IARC, World Health Organization: Nigeria. Available at https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/566-nigeria-fact-sheets.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2020.

8. Beaumont CE, Nwankwo E: Promoting early diagnosis of breast cancer in Nigeria using materials designed to cross communication barriers of fear, taboo, and literacy between health-care teams and the community at risk from breast cancer. JCO Global Oncol 4(suppl 2):jgo.18.58300, 2018.

9. Nwankwo E: MetaPink program: Simplifying the breast cancer journey for patients with advanced stage breast cancer in Nigeria. JCO Global Oncol 4(suppl 2):jgo.18.38600, 2018.

10. Aruah CS: The current status of cancer care in Nigeria: Challenges and solutions. Available at https://indico.cern.ch/event/767986/contributions/3357238/attachments/1813272/2969805/Simeon_in_botswana_-_the_current_status_of_radiotherapy_in_nigeria-2.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2020.