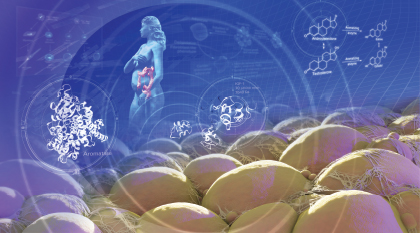

The above illustration depicts the labyrinth of etiologic pathways that may be involved in triggering the metabolic mechanisms leading to obesity-related cancers. (See “Understanding the Biologic Triggers” below.)

Illustration by Adam Questell © 2017

Research is still lacking to support a link between obesity and an increased risk of developing all types of cancer. Nevertheless, a review1 of more than 1,000 epidemiologic studies by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), a division of the World Health Organization, examining the preventive effects of weight control on cancer risk has found strong evidence that being overweight or obese increases the risk of developing at least 13 types of cancer. The cancer types include esophageal, gastric cardia, colorectal, liver, gallbladder, pancreatic, uterine, kidney, ovarian, meningioma, thyroid, and postmenopausal breast cancers, as well as multiple myeloma.

According to Graham A. Colditz, MD, DrPH, MPH, Associate Director of Prevention and Control at the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, and Chair of the IARC working group, taken together, these malignancies account for 20% of all new cancer diagnoses, making obesity the second greatest environmental risk factor for developing cancer after smoking. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 40% of all cancers diagnosed in the United States are linked to tobacco use.2

As we become more successful with tobacco control, we are left with obesity as a dominant cause of cancer, and the United States is leading the world in the level of overweight and obese people.— Graham A. Colditz, MD, DrPH, MPH

Tweet this quote

“As we become more successful with tobacco control, we are left with obesity as a dominant cause of cancer, and the United States is leading the world in the level of overweight and obese people,” said Dr. Colditz.

Concerning Statistics

Data show in just over 3 decades, the rate of obesity among adults in the United States has more than doubled and more than tripled among children.3 Today, more than one-third of Americans (over 72 million) are obese, and another one-third are considered overweight. Among adults, overweight is defined as a body mass index of 25 to 29.9 kg/m2 and obesity as a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or more.

In addition to increasing the risk of cancer onset, being overweight or obese also elevates cancer survivors’ risk of recurrence after initial treatment and can worsen overall survival, particularly in breast cancer4 and pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia.5 The devastating toll obesity takes on cancer occurrence and cancer-related death is found in the statistics: Each year, about 120,000 cancer diagnoses are attributed to excess body weight,6 which results in 15% to 20% of cancer-related mortalities.7 The association between excess weight and cancer onset has become so strong, ASCO devoted its December 10, 2016, issue of the Journal of Clinical Oncology (JCO) to the publication of studies investigating obesity and cancer prognosis, impact on treatment, potential biologic mechanisms, and approaches to weight loss.

Figure 1. Total Attributable Direct and Indirect Costs ($ Millions), by Condition, 2014. Source: Waters H, DeVol R.8 Reprinted with permission from the Milken Institute.

The impact of obesity on the health of the U.S. economy is devastating as well. According to a recent report by the Milken Institute, Weighing Down America: The Health and Economic Impact of Obesity, the total cost of treating health conditions related to obesity, including cancer, heart disease, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease, and the attendant loss of productivity at work exceed a staggering $1.4 trillion annually (see Figure 1)—more than twice what the United States spends on national defense.8

Understanding the Biologic Triggers

Although the exact hormonal and metabolic mechanisms that might trigger obesity-related cancer are not fully understood, research is beginning to shed light on a labyrinth of etiologic pathways involved in the process. According to a study9 published in JCO on the role of obesity in endometrial cancer risk—more than half of endometrial cancers are attributable to obesity—visceral fat is composed of adipocytes and preadipocytes, as well as infiltrating macrophages and stromal, nerve, and stem cells. Together, they secrete adipokines, which increase endometrial proliferation and promote tumorigenesis. In addition, adipose tissue is a source of mesenchymal stem cells, which support tumor growth and progression.

Adipocytes, preadipocytes, and mesenchymal stem cells within fat tissue are a source of aromatase, the enzyme responsible for the conversion of androgens to estrogen. Higher levels of estrogen in women with obesity cause increased cellular proliferation and increased double-stranded DNA breaks, contributing to genetic instability. Higher amounts of estrogen may also be responsible for the development of other cancers, including breast and ovarian cancers.

Finally, elevated levels of insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) as well as hyperglycemia in women with obesity can fuel endometrial growth and endometrial cancer progression. Higher levels of insulin and IGF1 may also explain the link between obesity and kidney and colorectal cancers.

Adipocytes in fatty tissue also produce chronic inflammation, a potential factor in the development of esophageal, liver, and colon cancers, and may influence the levels of certain tumor regulators, including the mTOR tumor regulator, which is involved in the onset of several cancers. The results from the IARC study show that obesity-associated inflammatory pathways may also be involved in the development of multiple myeloma.

“Inflammatory pathways are disturbed as the level of obesity increases. The question is whether the inflammatory pathways and increased cell turnover are, in part, driving the myeloma out of B cells,” said Dr. Colditz. “In fact, there are multiple ways that obesity can be driving cancers at different sites.”

Complications in Care

Once diagnosed with cancer, overweight or obese patients often face greater challenges during care than their leaner counterparts. They are more likely to develop surgical complications, such as infection and lymphedema, and imaging tests used to diagnose cancer and track its progression are often less effective due to reduced image quality. Obesity also interferes with the ability to deliver full doses of radiotherapy to a target location and complicates chemotherapy dose calculation.

Although chemotherapy dosing in adult patients with cancer has traditionally been based on a patient’s estimated body-surface area, the delivery of full standard–dose intensity chemotherapy is often not achieved in overweight and obese patients due to concerns that it might cause excessive toxicity. Data from ASCO’s clinical practice guideline on appropriate chemotherapy dosing for adult patients with cancer and obesity show that up to 40% of patients with obesity receive limited chemotherapy doses that are not based on actual body weight, with concerns about toxicity and overdosing being unfounded. The guideline recommends that full weight–based cytotoxic chemotherapy doses be used to treat these patients, especially when the goal is cure, to avoid compromising clinical outcomes.10

While chemotherapy underdosing has been associated with cancer recurrence and poorer survival outcomes in patients with obesity, research is showing that the same mechanistic factors that trigger cancer onset may also influence cancer recurrence and contribute to the worse survival outcomes in these patients.

We recognize that obesity is tightly linked to cancer risk. The same pathways that affect cancer risk, such as inflammation and higher levels of insulin, estrogen, and progesterone, are likely involved in cancer recurrence as well.— Jennifer A. Ligibel, MD

Tweet this quote

“Although it is true that underdosing of chemotherapy is linked to poor outcomes in patients with obesity, evidence suggests that the relationship between obesity and an increased risk of cancer recurrence and mortality is not driven primarily by treatment factors,” said Jennifer A. Ligibel, MD, Director of the Leonard P. Zakim Center for Integrative Therapies at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Assistant Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School, and Chair of the ASCO Energy Balance Work Group.

“We recognize that obesity is tightly linked to cancer risk,” she continued. “The same pathways that affect cancer risk, such as inflammation and higher levels of insulin, estrogen, and progesterone, are likely involved in cancer recurrence as well. In a study we performed looking at the relationship between body mass index and breast cancer recurrence in patients receiving doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and paclitaxel, dosed by actual body weight, there was a significantly higher risk of recurrence and mortality in the obese vs nonobese patients, regardless of tumor subtype and size.11 These data are consistent with other studies, so something about weight is linked to recurrence that can’t be explained away by treatment factors.”

Physician Bias

Despite the growing obesity epidemic over the past 3 decades, the health-care system and its practitioners remain woefully unprepared and often unwilling to treat overweight and obese patients. The quality of imaging modalities, such as ultrasound and x-ray, is usually reduced because of the distance the radiology beams have to pass through in large patients. Moreover, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scanners are not built big enough to accommodate very heavy patients. Although some imaging scanners now have maximum table loads of up to 650 lb, they are not yet available in many hospitals.

Worse still is evidence showing that physicians and other health-care professionals have negative opinions about people who are overweight or obese, which impedes patient communication, negatively affects patient outcomes, and reduces patient satisfaction. According to the results of a study by Phelan et al:

A common explicitly endorsed provider stereotype about patients with obesity is that they are less likely to be adherent to treatment or self-care recommendations, are lazy, undisciplined, and weak-willed. Second, primary care providers have reported less respect for patients with obesity compared with those without, and low respect has been shown to predict less positive affective communication and information giving. Third, primary health-care providers may allocate time differently, spending less time educating patients with obesity about their health.12

The study also found that body weight stigma discourages patients from seeking clinical care and that women with obesity, for example, are less likely to seek recommended screening for some cancers.

Oncologists’ Role

In recognition of the mounting evidence showing obesity as a major risk factor for cancer, in 2014, ASCO issued a position statement on obesity and cancer.7 The statement established a multipronged initiative to increase education and awareness of the evidence linking obesity and cancer; provide tools and resources to help oncology providers address obesity with their patients; build a robust research agenda to better understand the pathophysiology of energy balance alterations, evaluate the impact of behavior change on cancer outcomes, and determine the best methods to help cancer survivors make effective and useful changes in lifestyle behaviors; and advocate for changes in policy and systems to address societal factors contributing to obesity and improve access to weight management services for patients with cancer.

“Patients are looking for guidance because there is a lot of misinformation about strategies for losing weight. As oncologists, we owe it to our patients to study the most effective approaches to weight control so we can make evidence-based recommendations,” said Dr. Ligibel.

According to an analysis by the National Cancer Institute, if current trends continue, by 2030, there could be about 500,000 additional cases of cancer in the United States. The analysis also found that if every adult reduced his or her body mass index by just 1%, about 100,000 new cases of cancer could be prevented.13

Because research on how losing weight might affect cancer risk has been limited, it is difficult to know whether shedding extra pounds once a person is already overweight or obese actually halts the mechanisms driving cancer onset. However, a recent study by Luo et al evaluating the association of weight change and endometrial cancer risk among postmenopausal women suggested that intentional weight loss could decrease that risk by 29% to 56%. The study, however, was limited to postmenopausal women, and it did not account for weight change beyond 3 years of follow-up.14

With regard to tobacco consumption, a lot of evidence has shown that once a person stops smoking, the risk for cancer falls significantly over a period of years. We just don’t have as much long-term experience with obesity....— Ernest Hawk, MD, MPH

Tweet this quote

“With regard to tobacco consumption, a lot of evidence has shown that once a person stops smoking, the risk for cancer falls significantly over a period of years,” said Ernest Hawk, MD, MPH, Vice President and Division Head of Cancer Prevention and Population Sciences and Boone Pickens Distinguished Chair for Early Prevention of Cancer at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. “We just don’t have as much long-term experience with obesity to know what level of risk mitigation might follow from a sustained loss of weight in an obese person, because, unfortunately, not many patients are successful at losing weight and keeping the weight off long term. But losing weight is certainly recommended for overall good health and for lowering the risk of other serious disorders like heart disease and diabetes.”

Bariatric Surgery May Reduce Cancer Risk

Evidence is beginning to emerge showing that patients with obesity who undergo bariatric surgery do decrease their cancer risk compared to individuals who have not undergone the procedure. An observational 2-cohort study by -Christou et al15 investigating the effect of bariatric surgery on cancer risk in morbidly obese patients found that it reduced that risk by about 80% over a 5-year follow-up period, with breast and colon cancers showing the greatest reductions—85% and 70%, respectively. The study compared 1,035 patients who had had bariatric surgery with 5,746 matched obese patients who had not undergone the procedure.

Neither group had previously been diagnosed with cancer. On average, patients who had the surgery lost 67% of their excess weight.

“We do have some provocative data coming from bariatric surgery studies that suggest for the first time that people who undergo the procedure have a significantly reduced risk of developing cancer compared to individuals who don’t. Although the studies are limited, the data suggest that there may be dramatic benefits from this surgery,” said Dr. Ligibel.

Guiding Patients on Weight Loss

In 2014, ASCO published Obesity and Cancer: A Guide for Oncology Providers (www.asco.org/sites/new - www.asco.org/files/content-files/blog-release/documents/obesity-provider-guide.pdf) to help physicians assess and manage their patients’ weight. The guide provides strategies to promote weight loss and prevent weight gain during survivorship, including lifestyle interventions such as calorie restriction and increased physical activity, as well as medical interventions like bariatric surgery.

Dr. Ligibel admits that starting a conversation about weight management with patients can be difficult. “I usually begin the conversation with information on the importance of physical activity and good nutrition rather than a discussion about weight, because clearly these are the factors that influence a person’s weight, but the topic can be emotionally charged,” she said.

We need to better understand how to leverage the teachable moments from cancer diagnosis through survivorship to educate families about lifestyle factors that affect weight control....— Melissa M. Hudson, MD

Tweet this quote

Broaching the subject of excess body weight can be especially difficult when the patient is a child or adolescent. “Previous studies have investigated strategies to promote healthy weight maintenance during and after childhood cancer treatment. The timing of these interventions is challenging, as families must consider making lifestyle changes while adapting to the cancer diagnosis and its treatment and side effects,” said Melissa M. Hudson, MD, Director of the Cancer Survivorship Division and the Charles E. Williams Chair on Oncology-Cancer Survivorship at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. “We need to better understand how to leverage the teachable moments from cancer diagnosis through survivorship to educate families about lifestyle factors that affect weight control and general health, such as physical activity and eating and drinking habits.”

Dr. Hudson suggests oncologists introduce the message of maintaining a healthy lifestyle at the time of diagnosis and reviewing the issue periodically at key milestones, such as achievement of remission, completion of therapy, and transition into long-term follow-up care, as appropriate. “These efforts aim to promote health across the survivorship spectrum and potentially reduce the risk of cancer recurrence, secondary cancers, and other health issues,” said Dr. Hudson.

Reducing the Impact of Obesity on Cancer

Tackling the causes of overweight and obesity and determining effective solutions to mitigate the problem and help people maintain a healthy weight throughout their lives are challenging. To make progress, ASCO suggests these three strategies:

- Build awareness in the medical community and among policymakers and the public of the connection between

cancer and obesity. - Invest in research to fully understand and address the links between obesity, cancer, and other diseases, and

apply the findings to develop effective obesity prevention and treatment interventions. - Advocate for enhanced obesity prevention and treatment, including access to healthy food, exercise programs, and weight-loss strategies.

For more information on ASCO’s position statements on obesity, CME events to learn more about treating obesity, and resources to help patients maintain a healthy lifestyle, visit www.asco.org/practice-guidelines/cancer-care-initiatives/prevention-survivorship/obesity-cancer. ■