Head and neck cancer and its treatment can result in a variety of neuromuscular and musculoskeletal pain and functional sequelae. Commonly seen conditions in patients with the disease include neck pain and spasm, hemifacial spasm, trismus, dysphonia, dysarthria, neuropathic pain, and salivary disorders, such as first bite syndrome, which can sometimes occur after surgery.

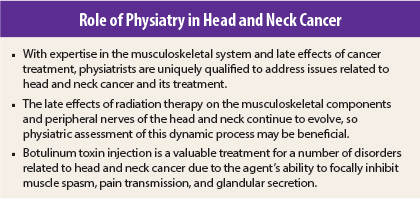

Physical medicine and rehabilitation physicians are able to use their knowledge of the musculoskeletal and neurologic systems and management of functional impairment to address these symptoms. The causes of these ailments vary but may include tumors in key neuromuscular structures in the head or neck, surgery, radiation, neurotoxic chemotherapy, or a combination of these factors. Preexisting disorders, such as diabetes or cervical spinal stenosis, may also adversely impact the manifestation of many disorders resulting from head and neck cancer and its treatment.1

Treatment Side Effects

Radiation is used extensively in the treatment of many types of head and neck cancers. Despite the continued evolution of radiation techniques intent upon providing maximal antineoplastic benefit with minimal damage to normal tissues, late effects from the treatment still develop.

The term radiation fibrosis describes the insidious pathologic fibrotic tissue sclerosis that occurs in response to radiation exposure, and radiation fibrosis syndrome describes the clinical manifestations that result from progressive fibrotic tissue sclerosis. Radiation fibrosis syndrome can affect any organ, system, or bodily function with potentially devastating implications for function and quality of life.

Surgical techniques for head and neck cancer have also evolved over the past few years, and while surgery now generally results in less morbidity, critical neuromuscular structures are often adversely affected. Among these is the spinal accessory nerve, which innervates the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles and is occasionally subject to resection or damage from the tumor itself, surgery, and/or radiation therapy. Compromise of the spinal accessory nerve often leads to pain and spasm in the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles with perturbation of shoulder function due to loss or dysfunction of the trapezius muscles as an important shoulder stabilizer.

Injecting the neurotoxic protein botulinum toxin into these muscles provides multiple therapeutic benefits owing to the presynaptic inhibition of the release of acetylcholine and other neurotransmitters. Approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the treatment of cervical dystonia, blepharospasm, primary axillary hyperhidrosis, chronic migraine, and strabismus, botulinum toxin is often used off-label for treating pain, abnormal muscle spasm, and excessive glandular secretions.

A role for the agent in the treatment of patients with head and neck cancer and associated disorders is also beginning to emerge. In addition to botulinum toxin, physiatrists may prescribe a combination of other medications, splints/braces, and exercises to mitigate pain in this setting.

Abnormal Muscle Spasm

Cervical dystonia, or neck spasm, is common in survivors of head and neck cancer as a result of neck dissection surgery and radiation therapy as well as tumors located in proximity to key structures such as the spinal accessory nerve. Ectopic activity in the spinal accessory nerve, which may occur as a result of surgery, radiation therapy, and/or chemotherapy, can cause pathologic and often painful spasm in the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. The scalene and other muscles, including flaps, are also commonly affected by surgery and/or radiation. Dysfunction of these muscles may lead to acquired cervical dystonia.

For patients complaining of pain, neck tightness, or loss of neck or shoulder range of motion, botulinum toxin is diluted with normal saline to the desired concentration and injected directly into the affected muscle. FDA-approved for the treatment of cervical dystonia in the general population, botulinum toxin has also shown efficacy in the treatment of muscle spasms after radiotherapy in survivors of head and neck cancer.1-3

Trismus, or impaired mouth opening, results in multiple medical and social complications, including decreased oral intake, impaired speech, compromised oral intimacy, inability to maintain oral hygiene and dental care, and reduced ability to visually survey for cancer recurrence. Although botulinum toxin injection has not been demonstrated to improve the oral opening when used in isolation, it has been shown to improve pain scores and oromandibular dystonia.4,5

Inhibiting pathologic masticator muscle spasm may be inadequate to improve mouth opening when the supporting tissues are also affected by radiation and surgical changes. The use of physical therapy and a jaw-stretching device such as the Dynasplint Trismus System following botulinum toxin injection may help improve this condition.6

The anti–muscle spasm effect of botulinum toxin injection may also be beneficial in treating synkinesis, hemifacial spasm, blepharospasm, pharyngoesophageal muscle spasms, and other disorders of pathologic muscle spasm resulting from malignant tumors, surgery, or radiation therapy.7-9

Pain Disorders

In addition to the inhibition of acetylcholine release, botulinum toxin is thought to inhibit the release of other neurotransmitters involved in the generation of pain. This effect was likely evident in the prospective facial pain and trismus trial by Hartl et al,4 which demonstrated improved pain scores but not trismus.

While botulinum toxin injections can cause systemic effects, the treatment does not generally spread far beyond the injection site, making it ideal for focal pain disorders. Injections of botulinum toxin have been shown to be beneficial in reducing chronic neuropathic pain in the head, neck, and shoulder following treatment of several tumor types.10,11

Abnormal Secretion Disorders

Botulinum toxin injection is FDA-approved for use in primary axillary hyperhidrosis, a disorder of abnormal glandular secretion. The ability of botulinum toxin to inhibit glandular secretion has applications in survivors of head and neck cancer as well. Botulinum toxin has emerged as a useful treatment for first bite syndrome12 and has demonstrated efficacy in reducing saliva flow temporarily with subsequent reductions in saliva-related complications and improved healing following surgery for certain types of head and neck cancer.13,14

Closing Thoughts

Only a few studies are currently available to test the safety and efficacy of botulinum toxin injection in patients with head and neck cancer. As the number of head and neck cancer survivors surges in the coming years, it is essential that we continue to investigate and optimize treatments for the multitude of neuromuscular, musculoskeletal, pain, and functional disorders that will afflict this population. ■

Disclosure: Dr. Stubblefield reported no potential conflicts of interest.

References

1. Stubblefield MD: Radiation fibrosis syndrome: Neuromuscular and musculoskeletal complications in cancer survivors. PM R 3:1041-1054, 2011.

2. Bach CA, Wagner I, Lachiver X, et al: Botulinum toxin in the treatment of post-radiosurgical neck contracture in head and neck cancer. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 129:6-10, 2012.

3. Van Daele DJ, Finnegan EM, Rodnitzky RL, et al: Head and neck muscle spasm after radiotherapy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 128:956-959, 2002.

4. Hartl DM, Cohen M, Julieron M, et al: Botulinum toxin for radiation-induced facial pain and trismus. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 138:459-463, 2008.

5. Lou JS, Pleninger P, Kurlan R: Botulinum toxin A is effective in treating trismus associated with postradiation myokymia and muscle spasm. Mov Disord 10:680-681, 1995.

6. Stubblefield MD, Manfield L, Riedel ER: A preliminary report on the efficacy of a dynamic jaw opening device (dynasplint trismus system) as part of the multimodal treatment of trismus in patients with head and neck cancer. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 91:1278-1282, 2010.

7. Laskawi R, Ellies M: The role of botulinum toxin in the management of head and neck cancer patients. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 15:112-116, 2007.

8. Behbehani R, Hussain AE, Hussain AN: Parotid tumor presenting with hemifacial spasm. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 25:141-142, 2009.

9. Hoffman HT, Fischer H, VanDenmark D, et al: Botulinum neurotoxin injection after total laryngectomy. Head Neck 19:92-97, 1997.

10. Wittekindt C, Liu WC, Preuss SF, et al: Botulinum toxin A for neuropathic pain after neck dissection. Laryngoscope 116:1168-1171, 2006.

11. Mittal S, Machado DG, Jabbari B: OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of focal cancer pain after surgery and/or radiation. Pain Med 13:1029-1033, 2012.

12. Laccourreye O, Werner A, Garcia D, et al: First bite syndrome. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 130:269-273, 2013.

13. Steffen A, Hasselbacher K, Heinrichs S, et al: Botulinum toxin for salivary disorders in the treatment of head and neck cancer. Anticancer Res 34:6627-6632, 2014.

14. Corradino B, Di Lorenzo S, Moschella F: Botulinum toxin A for oral cavity cancer patients. Toxins (Basel) 4:956-961, 2012.

Dr. Stubblefield is National Medical Director of Cancer Rehabilitation at Select Medical Corporation in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, and Medical Director of Cancer Rehabilitation at Kessler Institute for Rehabilitation in West Orange, New Jersey.

GUEST EDITOR

Physiatry in Oncology explores the benefits of cancer rehabilitation in oncology clinical practice to screen survivors for physical and cognitive impairments along the care continuum to minimize survivors’ disability and maximize their quality of life. The column is guest edited and occasionally written by Sean Smith, MD, Director of the Cancer Rehabilitation Program at the University of Michigan Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation in Ann Arbor.