Physical medicine and rehabilitation in oncology care explores the benefits of cancer rehabilitation in oncology clinical practice to screen survivors for physical and cognitive impairments along the care continuum to minimize survivors’ disability and maximize their quality of life.

According to a report from the American Cancer Society,1 studies show that multidisciplinary cancer rehabilitation—which often involves a team of rehabilitation professionals that includes physiatrists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech-language pathologists, and rehabilitation nurses—improves pain control, physical and cognitive function, and overall quality of life in cancer survivors. Yet, despite the proven benefits of cancer rehabilitation, the discipline is often underutilized in oncology care or is recommended after there is decline in a patient’s physical or mental function.

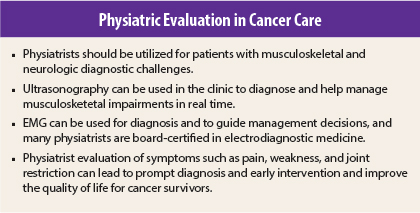

Physical medicine and rehabilitation physiatrists specialize in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of disorders related to the nerves, muscles, bones, and brain that may lead to temporary or permanent impairment and should be utilized to diagnose conditions as they arise, which could lead to earlier intervention and less symptom burden. As experts in musculoskeletal and neurologic conditions, physiatrists are able to assess pain, weakness, restrictions, and more to determine both a diagnostic workup and a treatment plan. This is an asset that should be incorporated into the multidisciplinary care of oncology patients.

When to Use Imaging and Other Tests for Cancer Pain

Physiatrists receive extensive training in the assessment of the musculoskeletal system, and during a patient’s physical exam, they can pick up impairment subtleties an oncology provider might miss. Musculoskeletal dysfunction, including pain, occurs frequently in patients with cancer and can cause both the patient and the provider to worry that the cancer has returned or spread, possibly leading to unnecessary tests and procedures. In fact, many of the aches and pains patients experience are not directly related to malignancy and can be managed as they would in a person without a history of cancer.

Physiatric evaluation may obviate the need for extensive testing or lead to more precise tests being ordered, saving time, reducing costs, and potentially resulting in fewer invasive diagnostic procedures that often carry risks of complications.

The need for imaging and other diagnostic tests continues to be evaluated, but evidence suggests that musculoskeletal issues lead to some level of unnecessary testing.2,3 Certainly, surveillance scans are essential in the continuum of patient care, but in-clinic symptoms can be assessed by a physiatrist, which may lead to quicker and more effective treatment as well as reassurance for both patients and oncologists.

Here is how physiatric evaluation of the musculoskeletal and neurologic systems may reduce the need for extensive testing.

Musculoskeletal Expertise

Using their extensive experience in treating musculoskeletal disorders, physiatrists consider a patient’s cancer diagnosis and treatment to determine the etiology of a specific impairment. For example, a patient who maintains a sedentary lifestyle while receiving chemotherapy will likely develop muscle atrophy and possibly hip pain. A physiatrist can discern whether this pain is consistent with bursitis/tendinopathy, osteoarthritis (or avascular necrosis in the setting of high-dose glucocorticoid administration), pelvic dysfunction, or a labral tear and whether the patient’s symptoms require further testing. A provider unfamiliar with hip joint pathology may order expensive and unnecessary tests in this setting, when, in fact, a diagnosis can be made clinically.

In addition to conducting a thorough musculoskeletal physical exam to evaluate problems, physiatrists will frequently use musculoskeletal ultrasound for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, which can result in earlier intervention, increased patient satisfaction, and elimination of the need for more costly imaging studies. Besides providing information to help physiatrists assess a patient for bursitis or tendinopathy, for example, the test can be used to guide an intra-articular hip joint injection. Ultrasonography will also reveal any intramuscular metastatic lesions, which would require additional studies to fully assess and would be coordinated with members of the oncology team to implement.

Physiatrists are also expert in evaluating spine pain, which is prevalent in patients with cancer and may be related to the cancer or caused by other factors. Differentiating among radiculopathy, peripheral mononeuropathy, and myelopathy pain can be challenging, but accurately evaluating the problem can help determine whether additional studies are needed to guide treatment. Physiatrists can also assess spinal stability in the setting of metastatic disease and may recommend treatment or surgical referral.

Electrodiagnostic Medicine

Many physiatrists are Board certified in both Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation and Electrodiagnostic Medicine and can diagnose neuromuscular disorders through electromyography (EMG). Examples of the utility of EMG in patients with cancer include determining whether limb pain is related to radiculopathy, confirming a diagnosis of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, monitoring chemotherapy toxicity, and even assessing the severity of routine disorders like carpal tunnel syndrome to guide treatment. Repeating studies can monitor a patient’s recovery or decline, and whether an EMG shows a pattern not expected in a typical recovery, a physiatrist may investigate the problem with different modalities.

Electromyography is an extension of a physiatrist’s physical examination and can determine whether there is neuromuscular damage, where the lesion or lesions are located, how chronic the problem is, and whether further testing may assist in the diagnostic process. Electromyography can also be used to monitor side effects from chemotherapy and may lead to treatment adjustment, improving patients’ quality of life.

Reducing Symptom Burden

A protocol known as the Prospective Surveillance Model evaluates patients prior to treatment, during chemotherapy administration, and as symptoms develop, with the goal of reducing symptom burden through early intervention.4 Electrodiagnostic evaluation can predict the development of neuropathy with different chemotherapeutic agents,5-7 and coordination between the medical oncology team and a physiatrist can help limit toxicity and symptom burden. Even if chemotherapy dosing is not titrated downward based on electrodiagnostic studies, interventions such as proactively increasing neuropathic pain medication, providing durable medical equipment for safe ambulation, engaging in a balance and strengthening program, and patient education can be initiated.

Electromyography can also diagnose myriad other processes, including myopathies, paraneoplastic syndromes, or neuropathic processes unrelated to chemotherapy. Once these disease processes are diagnosed, interventions can be used to minimize functional decline. ■

References

1. Silver JK, Baima J, Mayer RS: Impairment-driven cancer rehabilitation: An essential component of quality care and survivorship. CA Cancer J Clin 63:295-317, 2013.

2. Miller BJ, Avedian RS, Rajani R, et al: What is the use of imaging before referral to an orthopaedic oncologist? A prospective, multicenter investigation. Clin Orthop Relat Res 473:868-874, 2015.

3. Lavery HJ, Brajtbord JS, Levinson AW, et al: Unnecessary imaging for the staging of low-risk prostate cancer is common. Urology 77:274-278, 2011.

4. Stubblefield MD, McNeely ML, Alfano CM, Mayer DK: A prospective surveillance model for physical rehabilitation of women with breast cancer: Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Cancer 118(8 suppl):2250-2260, 2012.

5. Velasco R, Bruna J, Briani C, et al: Early predictors of oxaliplatin-induced cumulative neuropathy in colorectal cancer patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 85:392-398 2014.

6. Argyriou AA, Polychronopoulos P, Iconomou G, et al: Paclitaxel plus carboplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy: A prospective clinical and electrophysiological study in patients suffering from solid malignanciesstu. J Neurol 252:1459-1464, 2005.

7. Stubblefield MD, Slovin S, MacGregor-Cortelli B, et al: An electrodiagnostic evaluation of the effect of pre-existing peripheral nervous system disorders in patients treated with the novel proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 18:410-418, 2006.

Disclosure: Dr. Smith reported no potential conflicts of interest.

GUEST EDITOR

Physiatry in Oncology explores the benefits of cancer rehabilitation in oncology clinical practice to screen survivors for physical and cognitive impairments along the care continuum to minimize survivors’ disability and maximize their quality of life. The column is guest edited and occasionally written by Sean Smith, MD, Director of the Cancer Rehabilitation Program at the University of Michigan Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation in Ann Arbor.