At the 2011 Pan-Pacific Lymphoma Conference in Kauai, Hawaii, Andreas Engert, MD, Chairman of the German Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group (GHSG) and Professor of Medicine at the University Hospital of Cologne, Germany, discussed the treatment of nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL), a variant with a slightly better prognosis than classical Hodgkin lymphoma.

At the 2011 Pan-Pacific Lymphoma Conference in Kauai, Hawaii, Andreas Engert, MD, Chairman of the German Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group (GHSG) and Professor of Medicine at the University Hospital of Cologne, Germany, discussed the treatment of nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL), a variant with a slightly better prognosis than classical Hodgkin lymphoma.

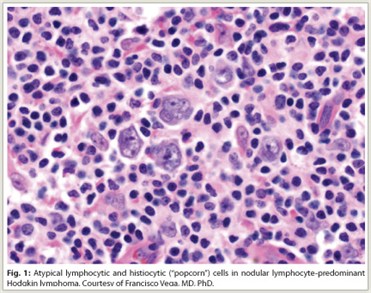

Lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (LPHL) accounts for approximately 5% of all Hodgkin lymphoma cases in Western countries. Histologically, LPHL presents with a nodular pattern (NLPHL) in more than 99% of cases, with the remainder presenting with a diffuse pattern. NLPHL is characterized by atypical lymphocytic and histiocytic or “popcorn” cells embedded in a nodular background consisting of small B lymphocytes and other reactive cells (Fig. 1). Lymphocytic and histiocytic cells usually express the B-cell marker CD20 and lack expression of CD15 and CD30, which are the characteristic markers of classical Hodgkin lymphoma.

Compared with classical Hodgkin lymphoma, NLPHL is associated with less aggressive tumor growth and lymphadenopathy, which often precede the diagnosis by many years, and a somewhat better prognosis. Patients with early favorable NLPHL (ie, without risk factors) have an excellent prognosis compared with those in early stages with risk factors (early unfavorable) or advanced stages.

Compared with classical Hodgkin lymphoma, NLPHL is associated with less aggressive tumor growth and lymphadenopathy, which often precede the diagnosis by many years, and a somewhat better prognosis. Patients with early favorable NLPHL (ie, without risk factors) have an excellent prognosis compared with those in early stages with risk factors (early unfavorable) or advanced stages.

Current treatment of NLPHL using standard Hodgkin lymphoma protocols may lead to complete remission in 95% of patients. Patients with early unfavorable and advanced stages are usually included in treatment protocols for classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Treatment of early NLPHL is less defined and includes radiotherapy, combined-modality treatment, and, more recently, the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab (Rituxan).

Treatment Outcomes in NLPHL vs Classical Disease

In a retrospective analysis of the GHSG database including 394 patients with NLPHL and 7,904 with classical Hodgkin lymphoma, complete remission after first-line treatment was achieved in 91.6%, 85.7%, and 76.8% of NLPHL patients in early favorable stages, early unfavorable stages, and advanced stages, respectively, compared with 85.9%, 83.3%, and 77.8%, respectively, of patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma.1 At a median of 50 months, freedom from treatment failure was observed in 88% of NLPHL patients and 82% of those with classical Hodgkin lymphoma (P = .0093), with overall survival of 96% and 92%, respectively (P = .0166). Among NLPHL patients, freedom from treatment failure rates were 93%, 87%, and 77% in early favorable, early unfavorable, and advanced stages, respectively.

‘Watch-and-Wait’ in Pediatric Patients

Watch-and-wait strategies have been used in select pediatric patients with NLPHL to avoid adverse effects of treatment. A French study reported several years ago that included primarily children with stage I disease showed that whereas event-free survival was improved with conventional Hodgkin lymphoma treatment vs observation after lymphadenectomy, there was no difference in overall survival between the two approaches (100% at 70 months).2 The findings indicate that watch-and-wait is a reasonable strategy after lymphadenectomy in this population.

Radiotherapy/Rituximab for Early Favorable Disease

For adult patients with stage IA disease without risk factors, involved-field radiotherapy alone may be optimal treatment. A GHSG analysis showed that involved-field radiotherapy was as effective as extended-field radiotherapy and combined-modality therapy in an analysis of 131 patients with stage IA NLPHL without risk factors.3 Complete remission was observed in 100% of patients after involved-field radiotherapy, 98% after extended-field radiotherapy, and 95% after combined-modality therapy. Freedom from treatment failure was 96% with involved-field radiotherapy after 19 months of follow up, 89% with extended-field radiotherapy after 72 months, and 93% with combined-modality therapy after 70 months.

Since CD20 is consistently expressed on NLPHL cells, use of the CD20-directed monoclonal antibody rituximab is rational, and promising results have been seen with the agent in relapsed NLPHL. In a recently reported small phase II study of rituximab in previously untreated patients with early stage IA disease, complete remission was achieved in 85.7% of patients; the overall survival rate was 100% at a median follow-up of 43 months, and progression-free survival rates were 96.4%, 85.3%, and 81.4%, at 1, 2, and 3 years, respectively.4 Although these results appear to be inferior to those with radiotherapy or combined-modality approaches in early-stage disease, further investigation of anti-CD20 antibody–based combinations in this setting is warranted.

ABVD for Early Favorable Disease

Recent GHSG studies have involved investigation of changes to standard Hodgkin lymphoma regimens. The GHSG HD10 study, which compared four vs two cycles of ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine), each followed by 20 or 30 Gy involved-field radiotherapy in 1,370 patients with newly diagnosed early favorable Hodgkin lymphoma, found that two cycles of ABVD plus 20 Gy was as effective as four cycles plus 30 Gy.5 At 5 years, freedom from treatment failure rates were 93.0% with four cycles and 91.1% with two cycles and overall survival rates were 97.1% and 96.6%, respectively; no differences in freedom from treatment failure or overall survival were observed according to radiotherapy treatment used. Toxicity was worst with the four-cycle/30-Gy regimen.

BEACOPP vs ABVD for Early Unfavorable Disease

The HD11 trial showed that moderate dose escalation using the BEACOPPbaseline regimen (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine [Matulane], and prednisone) did not significantly improve outcome in early unfavorable Hodgkin lymphoma and that four cycles of ABVD should be followed by 30 Gy of involved-field radiotherapy.6 The trial compared four cycles of BEACOPPbaseline vs a standard regimen of four cycles of ABVD, each with either 20 or 30 Gy of involved-field radiotherapy, in 1,395 patients. The BEACOPP regimen was more effective than ABVD when followed by 20 Gy radiotherapy (5-year freedom from treatment failure difference of 5.7%), but there was no difference between regimens when followed by 30 Gy (1.6% difference). There was no difference between 20 Gy and 30 Gy following BEACOPP, whereas inferiority of 20 Gy to 30 Gy (–4.7% difference) following ABVD could not be excluded. Toxicity was greatest in the more intensive treatment arms.

BEACOPP for Advanced Disease

The 10-year follow up of the HD9 trial in 1,196 patients with advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma indicates a stabilized significant improvement with eight cycles of an escalated-dose BEACOPP regimen (BEACOPPesc) (10-year freedom from treatment failure = 82%, overall survival = 86%) compared with eight cycles of BEACOPPbaseline (70%, 80%) and eight cycles of alternating cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone (COPP)/ABVD (64%, 75%)—P < .001 overall, and P < .0001 and P = .005 for freedom from treatment failure and overall survival comparisons, respectively, between the two BEACOPP regimens).7 These findings challenge ABVD as the standard of care for advanced-stage disease.

The ongoing HD18 trial is examining use of positron-emission tomography (PET) for detection of residual nodes after two cycles of BEACOPPesc in patients with advanced-stage disease. The trial is asking whether rituximab will improve outcome when added to BEACOPP in those with positive findings and whether a shorter course of BEACOPP is as effective as a longer course in those with negative findings. Patients with positive PET findings are receiving six additional cycles of BEACOPP with or without rituximab. Those with negative findings are receiving either two or six additional cycles of BEACOPP.

The ongoing HD18 trial is examining use of positron-emission tomography (PET) for detection of residual nodes after two cycles of BEACOPPesc in patients with advanced-stage disease. The trial is asking whether rituximab will improve outcome when added to BEACOPP in those with positive findings and whether a shorter course of BEACOPP is as effective as a longer course in those with negative findings. Patients with positive PET findings are receiving six additional cycles of BEACOPP with or without rituximab. Those with negative findings are receiving either two or six additional cycles of BEACOPP.

Treatment Recommendations

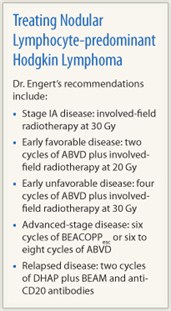

In summary, current recommendations for treatment of NLPHL include: involved-field radiotherapy only, at 30 Gy, for stage IA disease; two cycles of ABVD plus involved-field radiotherapy at 20 Gy for early favorable disease; four cycles of ABVD plus involved-field radiotherapy at 30 Gy for early unfavorable disease; and either six cycles of BEACOPPesc or six to eight cycles of ABVD for advanced stages of disease. For relapsed disease, options include two cycles of DHAP (dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin) plus BEAM (carmustine [BiCNU], etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan) and anti-CD20 antibodies.

In commenting on current treatment approaches to NLPHL, Dr. Engert noted, “We should try to treat NLPHL patients within clinical trials if possible” in the continuing effort to identify optimal treatment regimens. ■

Disclosure: Dr. Engert reported no potential conflicts of interest.

References

1. Nogová L, Reineke T, Brillant C, et al: Lymphocyte-predominant and classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma: A comprehensive analysis from the German Hodgkin Study Group. J Clin Oncol 26:434-439, 2008.

2. Pellegrino B, Terrier-Lacombe MJ, Oberlin O, et al: Lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin’s lymphoma in children: Therapeutic abstention after initial lymph node resection—a study of the French Society of Pediatric Oncology. J Clin Oncol 21:2948-2952, 2003.

3. Nogová L, Reineke T, Eich HT, et al: Extended field radiotherapy, combined modality treatment or involved field radiotherapy for patients with stage IA lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin’s lymphoma: A retrospective analysis from the German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG). Ann Oncol 16:1683-1687, 2005.

4. Eichenauer DA, Fuchs M, Pluetschow A, et al: Phase 2 study of rituximab in newly diagnosed stage IA nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma: A report from the German Hodgkin Study Group. Blood 118:4363-4365, 2011.

5. Engert A, Plütschow A, Eich HT, et al: Reduced treatment intensity in patients with early-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med 363:640-652, 2010.

6. Eich HT, Diehl V, Görgen H, et al: Intensified chemotherapy and dose-reduced involved-field radiotherapy in patients with early unfavorable Hodgkin’s lymphoma: Final analysis of the German Hodgkin Study Group HD11 trial. J Clin Oncol 28:4199-4206, 2010.

7. Engert A, Diehl V, Franklin J, et al: Escalated-dose BEACOPP in the treatment of patients with advanced-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma: 10 years of follow-up of the GHSG HD9 study. J Clin Oncol 27:4548-4554, 2009.